Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation since 11/26/17 in all areas

-

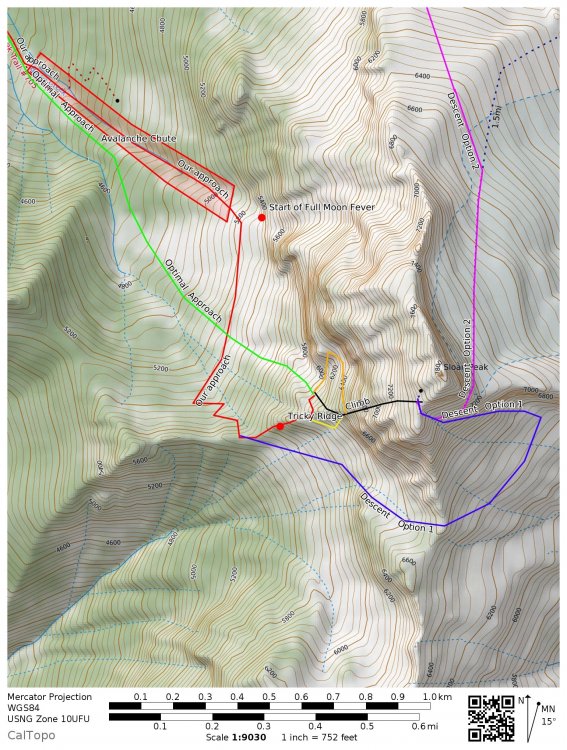

Trip: North Cascades - Sloan Peak - Superalpine (WI3-4, 1000') 04/17/2022 Trip Date: 04/17/2022 Trip Report: Fabien and I climbed Superalpine this past Sunday and topped out on Sloan peak. History: This route was attempted on 02/28/2020 by Kyle and Porter and on 03/15/2020 by Porter and Tavish We left Saturday afternoon, got the car to about 2000ft on FS 4096 just before the snow became continuous. We skinned in with overnight gear and setup camp near a small accessible stream feeding Bedal Creek at 3600ft. Sunday we woke up at 4:00 a.m. and we're breaking trail soon after. We found an easy crossing across the creek at 3950ft and stayed climber's right of the moraine to avoid being in an avy path until we were forced back in the forest. We started seeing the route peeking through the trees and reached the large snow field below the West face of Sloan peak. We approached up to the base of a left leading couloir and stashed the skis there (A). Route: We booted up the couloir, encountered a small step (B) and roped up at (C). (C-D) Short WI4 followed by easier climbing. Careful with rope drag on the rock if the belayer is in the sheltered area before the ice. (D-E) Short ice steps separated by snow. Setup an anchor on the right side at (E) (E-F) Left leaning ice staircase in what looks like a dihedral. (F-G) Snow up to a belay stance in a 5ft step. (G-H) Small ice step then snow up to belay in thin ice. (H-I) Mostly snow with some good ice screw placements. Belayed off a snow anchor. (I-J) 30ft of Easy mixed climbing. Placed cams 0.5 to 1 and made a snow anchor on a wind hardened snow fin: (J-K) Snow bowl. This can have a lot of sluffing and is dangerous if the snow is unstable. We were able to follow a path up that had already sluffed away. It was mostly the top 2in of snow that had fallen the previous night. (K-L) Snow bowl up to a notch on the ridge slightly climbers right (L-M) About 200ft of ridge traverse to the summit. Descent: (J-N) We decided to go down the snow ramp on the other side of the mountain that the corksrew follows for a bit. We aimed for a gendarme (Below the N). From there we did one 30M rappel off and traversed under the gendarme to the corkscrew route (O). By then the East side of Sloan Peak was in the shade and we found good snow to front-point sideways and down a ramp for almost 1000ft. (650ft elevation loss) There was a moat at the bottom which we negotiated skier's right. We had brought two poles up for the next section that involved wallowing across the bottom of the SE face to reach the South ridge of Sloan at 6750ft. (P) From there, we headed back to the W ridge near where the route starts (Q). It doesn't look like it can be traversed easily a first but there's a passage around 6100ft. At this point, we could see our skis and felt like it was in the bag. The chute skied amazingly well but once we reached the snow field, the snow had started to crust making it quite hard to turn. We arrived back at camp at dark pretty tired. Since we both had engagements on Monday, we slept until 4:00 a.m then skied most of the way back and made it home by 11:00 a.m. Overall, this is a fun route when the conditions are there. The snow bowl at the top is probably the most dangerous part of the route when the snow is unstable. It may be possible to bypass by staying on the ridge (Probably from J). Strava GPX Enjoy! Gear Notes: Gear: 11 ice screws (Used all) 8 draws 2 pre-rigged quads 0.3 - 2" cams 1 picket (2 would be better) Small Nuts (Unused) Approach Notes: Drive from Darrington while Bedal pass is closed. High clearance vehicle recommended for FS 409620 points

-

We are not dead! That was extremely trying. The server totally crashed in a terrible way right in the middle of a super intense week at work for me and I was taxed mentally to the max figuring this out. Luckily I have a couple really good friends, ex-coworkers...but they are friends to give me moral support and confidence to do everything I did which was rebuild everything on modern software. So the site is in a MUCH better place than it was pre-crash. I still have a bunch of maintainance to do, but the site is back up and going. Thank you for sticking around. We WILL keep this place alive dammit.18 points

-

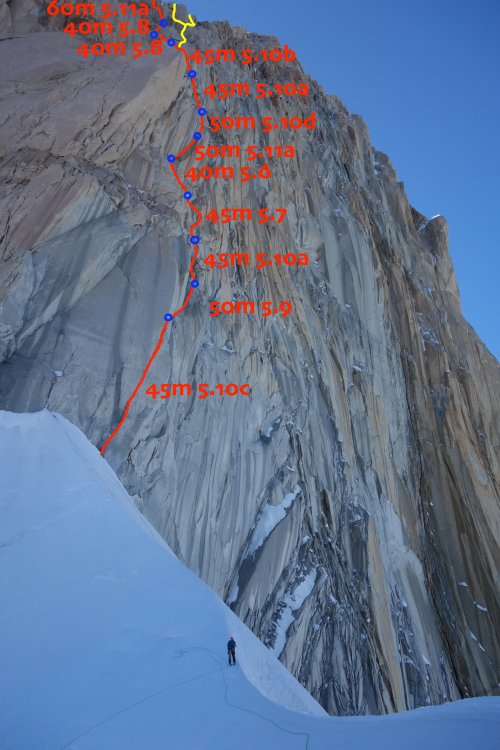

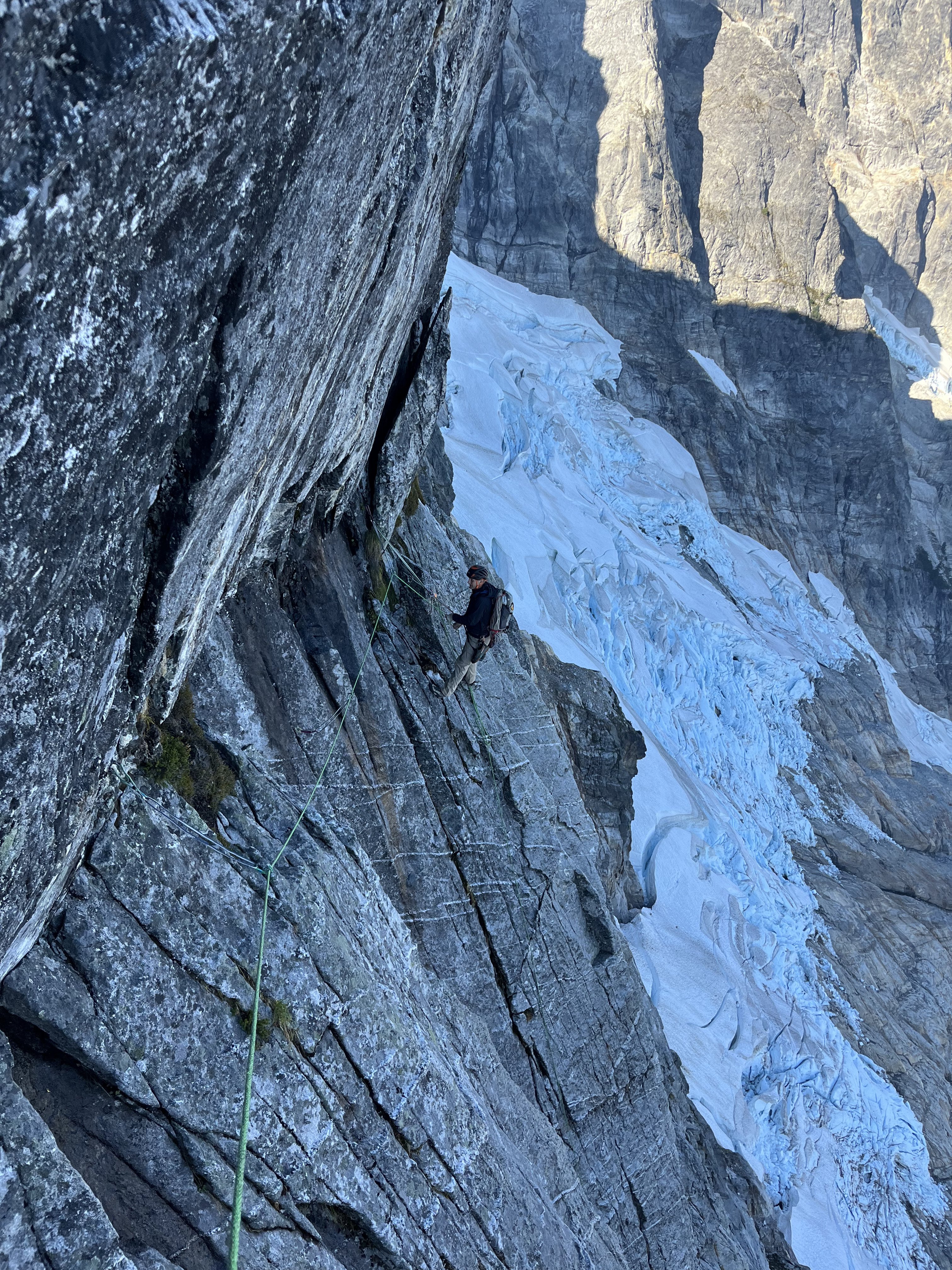

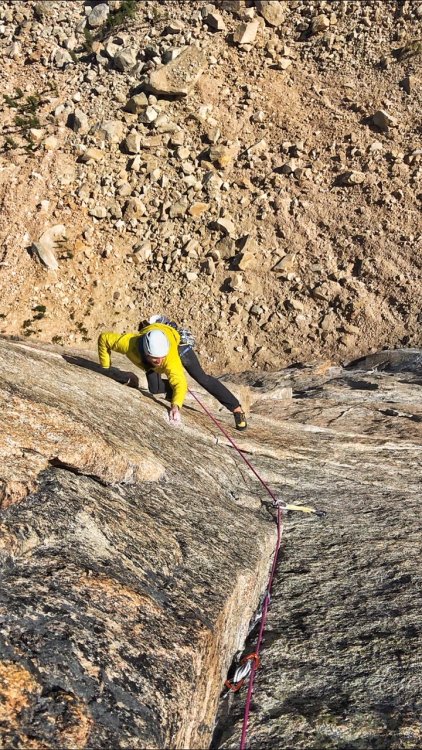

Trip: Baffin Island - Auyuittuq Trip Date: 08/02/2024 Trip Report: Prologue If a memory cannot be refuted by evidence than it must be the truth so I present this memory as such even if I have some misgivings whether it is in fact the case. I entered Western Washington University in 1991 and as a freshman living on campus I would frequently find myself in the Wilson Library thumbing through what already felt like an antiquated copy of Doug Scott’s “Big Wall Climbing”. Published in 1974 it was only seventeen years old but felt a world apart from the climbing culture and techniques of the early 1990’s. Within a chapter entitled “The Development of Big Wall Climbing in Remote Regions” the author had written a detailed description of his recent expeditions to Baffin Island. And I would claim it was here I first became aware of Mount Asgard. Asgard, a tremendous granite turret with an ice-covered summit plateau rearing 3,000 vertical feet out of an endless labyrinth of glacier ice. The “Scott Route”, a 4,000 foot-long free climb following a beautifully sculpted pillar of exquisite granite. This was clearly a route I wanted to climb. In fact it was The Route I wanted to climb and for over thirty years it always remained as such. A fantasy at the top of my bucket list exceeding the ability, vision or time I had available at different stages of my life. A transcription of our logbook entry at the Thor Emergency Shelter written on July 28th, 2024 We arrived in Pangnirtung on July 3rd. A healthy snowpack and a cool spring had left the mountains still draped in snow and the head of the fjord still covered in ice. A fortunate warm and windy day broke up the ice and on July 5th we entered the park, arriving here on the 6th under cold, leaden skies in a stiff wind Establishing basecamp, we were then unknowingly blessed with largely cool dry days that alternated between overcast and windy or quiet and partly cloudy. The ice slowly melted from the river, the snow on the peaks melting even slower. The first wildflowers bloomed and the days grew perceptibly warmer, Via both success and failure we developed our understanding of these mountains. Huge approaches, difficult climbing, long descents. On our second attempt we climbing the southwest ridge of Mount Menhir, the looming monolith just west of the hut. We were also fortunate to establish two first ascents on impeccable rock with relatively easy access and quick descents. On the large slab wall approximately 40 minutes up valley we linked beautiful splitters into a ten pitch 5.9 we called “Pang Ten”. Later we climbed it again and added sturdy rap anchors. With a twenty minute approach from the trail and no summit it’s a crag climb on Baffin! Above “Pang Ten” we eyed the beautiful flowing east buttress of the East Tower of Northumbria. From the hut here it’s the right skyline of the rightmost peak of the Northumbria group. With binoculars you can pick out the extensive splitters we climbed just this side of the skyline. Eight pitches of moderate 5.8-5.9 climbing on the most perfect rock. Just pure fun and now setup with solid rap stations. The link up of these two routes would make for an amazing Grade V climb without the extensive approaches or difficult descents of other long routes. Highly recommended! July 19th through the 22nd brought the stable, clear weather climbers dream of on Baffin. A long casual approach with a nice siesta at Summit Lake took us to a high bivi on a thankfully melted out Caribou Glacier. Starting at 1 am on the 20th we approached the fabled Scott Route on the North Summit of Asgard. 1200 meters of climbing over 23 pitches took us to the summit at 10 pm. Witness to a spectacular sunset, an endless sea of jagged peaks like diamonds in the periwinkle glow of the midnight sun. Being on that summit is as “out there” as we’ve ever been. The descent was long and tenuous with terrible snow conditions. We returned to our high camp 30 hours after leaving it. Since then the weather has deteriorated into more typical Baffin conditions, lots of rain, snow in the mountains and strong winds. Thoughts turn to home and family as our remaining days here melt into one another. Yesterday we hauled our first load out to Schartzenbach Falls, tomorrow on the 29th we leave for good. Our stay here has been perfect. So many memories. The intensity and beauty of the high peaks balanced by many wonderful rest days here around the hut, mending clothes, doing laundry, cooking, reading and soaking in the views. The world is vast and we may never return to this location again but our memories will always be of much contentment here, we wanted for nothing. Darin Berdinka (Bellingham, WA) & Owen Lunz (Lafayette, CO) 7/6/24-7/29/24 View up fjord upon arrival in Pang Starting the approach in inclement weather Basecamped next to and occasionally in the Thor Emergency Shelter. Mount Menhir in background. Left skyline is SW Ridge V 5.9. Starting up the southwest ridge of Menhir. Twelve pitches. Possibly 3rd ascent based on archeological assessment of rappel tat. Supernatural alpine beauty Pano from basecamp. Menhir on left, multiple summits of Northumbria on right. Looking up the Active Recovery Wall. Forty minutes up valley of the Thor Hut. Surprised to find no evidence of prior passage. Pitch 5 or so, climbing perfect splitters. Enjoyable corners high on the slab. Thor in background. Top of the slab. A few days later we'd climb the clean 1200' buttress just right of Owen. Approaching the East Tower of Northumbria. Pulling through a roof on perfect locks and crimps. Most of the climbing was in lovely splitters on the best imaginable rock. Summit views out over largely untrodden peaks. View out over Weasel River Valley with Thor across the way once again. View down valley from Summit Lake Emergency Nap in the Emergency Adirondack Chairs at the Summit Lake Emergency Shelter. Looking out over the Parade Glacier at 3 am. Asgard on left. Frigga on right. Another party was establishing a new A5 route on the left most pillar of Frigga that day. Asgard. Route started along right side of square snowpatch. 2nd pitch. Runout slabs. I look stupid in this photo but it does provide an excellent view of the upper pillar. Abandoned equipment high on the route. What epic unfolded here? 2nd to last pitch. Wet, wide and exhausting. Sunset view from just below summit. The artic gloaming. Loki in foreground. Epilogue So on a lovely day in the summer of 2024, several weeks after having climbed Asgard via the Scott Route I returned to the Wilson Library to see if I could track down the book. The library and its grounds felt little changed and somewhat surprisingly the book was still there, biding its time on a dusty shelf. Despite now being three times older than when I first perused it the book felt no more antiquated then it once had. And despite the passage of thirty-three years since those august days of youth I pleasantly realized that, on this day at least, I didn’t feel significantly different either. Other Images The incomparable Breidalblik Peak. Sun/shade line climbed in 1971 at V 5.9 A1. On the wrong side of the river for easy access. Bivi on the Caribou Glacier. Mount Tyr and Mount Walle in background. West Face of Mount Thor Signs of life below Mount Sif. Gear Notes: standard rack Approach Notes: Fly to Pangnirtung. Boat twenty miles up fjord. Hike 25 miles to Asgard. Supplies can be hauled in by sled in winter. Contact Peter Kilabuk.18 points

-

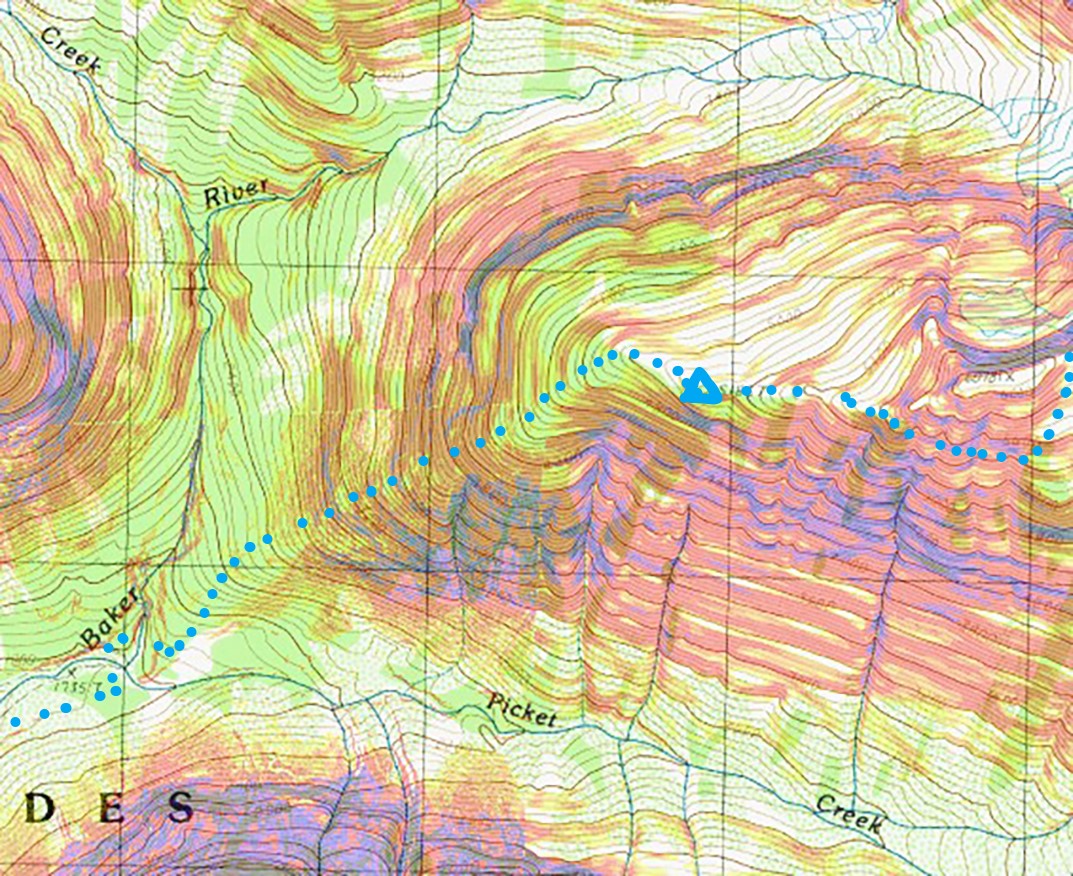

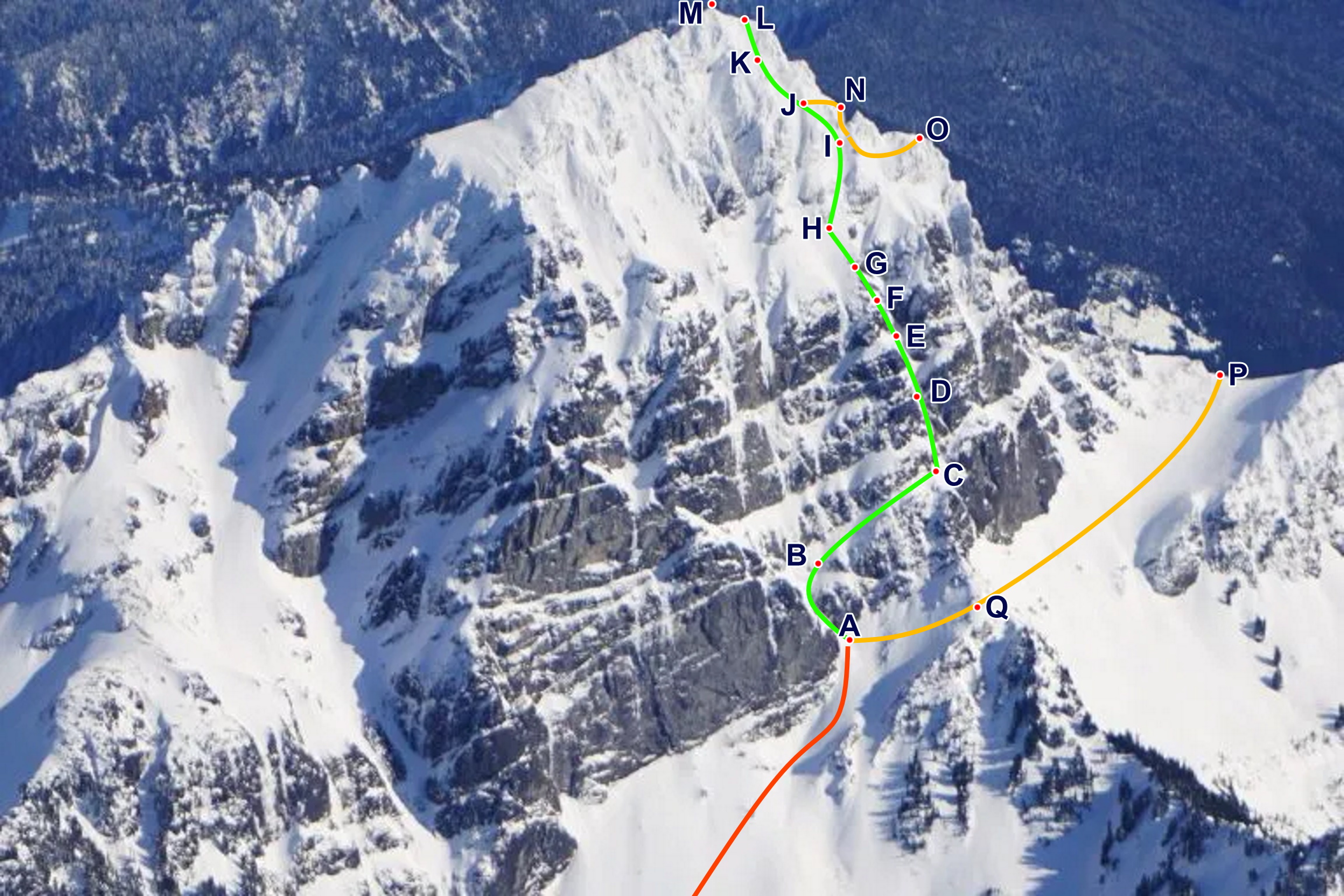

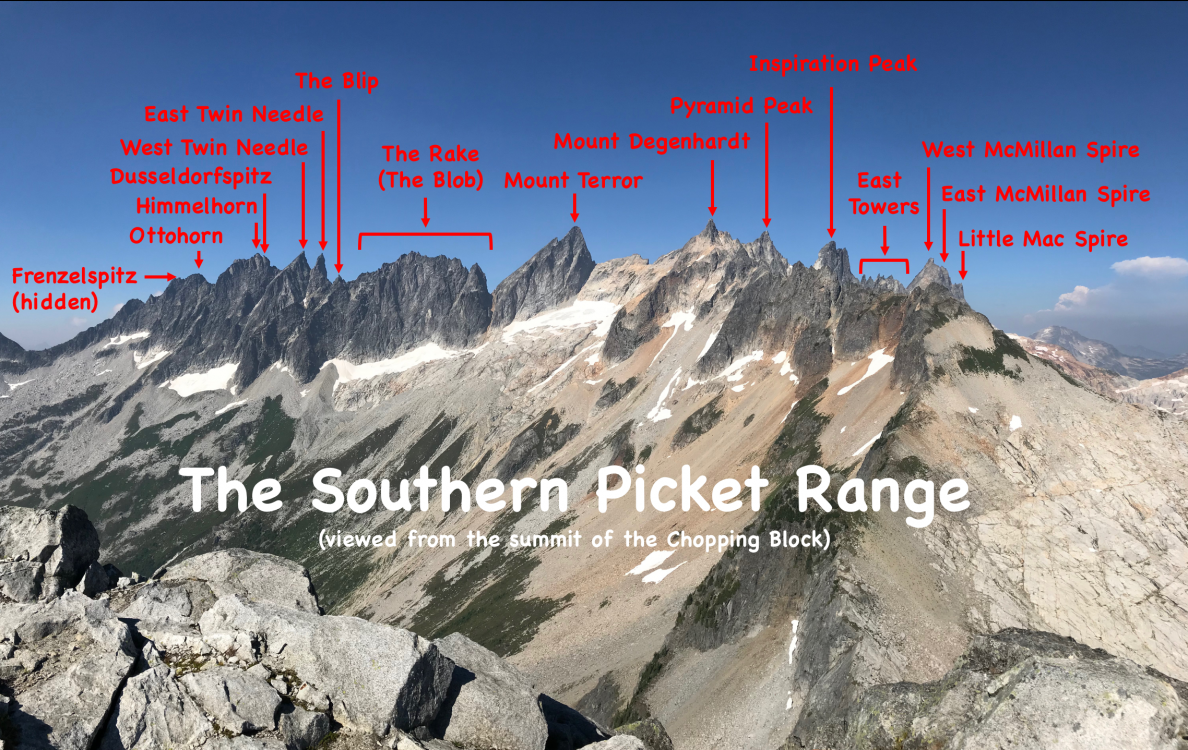

Trip: Winter Hard Mox and Spickard - West Ridge, South Face Trip Date: 12/29/2023 Trip Report: Hard Mox (8,504 ft) and Mt Spickard (8,979 ft) Winter Ascents Eric and Nick Dec 27 – Jan 2, 2023-2024 First Winter Ascent of Hard Mox, Second Winter Ascent of Spickard On the summit of Hard Mox Dec 27 – Double carry zodiac boat and gear from Ross Dam trailhead to Frontage road, drag boat to Ross Lake, motor to Little Beaver, hike to Perry Creek shelter Dec 28 – Bushwhack to upper Perry Creek basecamp Dec 29 – Climb Hard Mox via Perry Glacier to West Ridge route (M5 WI2 5-pitch), return to basecamp, 18 hours camp to camp Dec 30 – Bad weather day, rest in camp (rain all day) Dec 31 – Climb Spickard via south face Jan 1 – Bushwhack down Perry Creek, hike to Little Beaver, paddle 9 hours down Ross lake when motor doesn’t start, drag boat up Frontage road, triple carry up trail to truck by 3am Jan 2 – Drive home The route Hard Mox is considered the most difficult of the Washington Hundred Highest/Bulger peaks, and had previously never been climbed in winter. I’m working on climbing all the Bulgers in winter and this peak is the crux of that list. Hard Mox has numerous elements that make it uniquely challening in winter. 1. It is very remote. The nearest road on the US side of the border is 15 miles away line of sight (Hannegan Pass trailhead), and the second closest 18 miles away (Ross Dam Trailhead). Hiking mileage from these trailheads is close to 30 miles, and the trails are likely snowed-over and unbroken in winter. Note: I’m following a rule that ascents must be made legally, so I don’t count roads or trails on the Canadian side of the border. One way to shorten the approach is to take a water taxi run by the Ross Lake resort. These don’t operate in winter, though, so that isn’t an option. Detailed route view 2. The peak is technical. The easiest summer route is 4-pitch 5.6. It was unclear if this was the best winter route, though, since the peak hadn’t been climbed in winter. 3. The weather is unstable in winter. Hard Mox is in the West North zone of the cascades, which generally has more precipitation and less stable weather than other zones. This also means the avalanche conditions are more likely to be unstable in this zone in winter. 4. There are no trails to the peak (on the US side). Bushwhacking is required, and this can be very challenging in the North Cascades, especially in winter. Climbing Hard Mox in July 2018 (photo by Steven) I first climbed Hard Mox in July 2018 with Steven Song, and we entered and exited via Canada. We followed the standard Depot Creek approach, crossed the ridge of Gendarmes to the south face of Hard Mox, descended to the base of the south gully, then climbed up the gully and to the summit via the West Ridge. This is the route that nearly all climbers take to climb Hard Mox. In 2020 I started considering how to climb Hard Mox in winter. I’m following a rule that all winter ascents must be completely legaly (no sneaking in from Canada), so I needed to find an alternative approach. I considered three approach options, and made scouting trips to determine the feasibility of each in winter. Over the next three years I would make a half-dozen scouting trips and two unsuccessful winter attempts on Hard mox. Scouting the Ross Dam approach and paddling Ross Lake in November 2020 First, I considered the Ross Dam trailhead approach. This route is to start at the Ross Dam trailhead, hike up the lake to Big Beaver, then hike to Redoubt Creek and bushwhack up to meet the summer route. This route is 30 miles one way. It has the advantage that the first half is mostly low elevation and often snow-free in winter, though it requires crossing Beaver Pass, which would likely be snow covered. In mid November, 2020 I did a trip where I hiked this approach to Redoubt Creek, then continued to Little Beaver and packrafted back to Ross Dam in a big loop. That approach would probably take two days in good conditions in winter. Scouting the Hannegan Pass approach in December 2020 I next considered the Hannegan Pass approach. This would require hiking or skiing in from the Hannegan Pass trailhead to the Chilliwack River, bushwhacking up Bear Creek, then meeting up with the standard summer route at the Redoubt-Easy Mox col. It would be about 28 miles one way. In December 2020 I drove up the road towards the Hannegan Pass trailhead and found a sign that the road is groomed for skiing in winter and closed to snowmobiles. This meant there would be an additional 5-mile approach in winter, making the approach 33 miles. I skied up the trail to near Hannegan Pass, but progress was slow. That approach would probably take at least two days. Those approaches would be too long for me to squeeze Hard Mox in a regular weekend or even a 3-day weekend. Ideally I could find a one-day approach so Hard Mox could be possible in one of my two long holiday weekends of the winter (presidents day weekend and MLK day weekend). I’m a teacher so can’t take vacation days, meaning these holiday weekends are my options in winter. I next considered a boat approach on Ross Lake. I have a packraft, but I discovered it can take most of a day to paddle between Little Beaver and Ross Dam. I really needed that to take on the order of a few hours so the rest of the day can be used for hiking and bushwhacking in. For that to be feasible the boat really needed to be motorized. Ross Lake is in the unique situation that motorized boats are allowed on the lake, but there is no road access for the general public. It is possible for workers at the dam or at the Ross Lake resort to drive to the lake by taking a vehicle ferry from the town of Diablo to upper Diablo lake, then driving up Frontage road connecting the two lakes. This service is not available to the public, meaning Frontage road is not reachable by vehicle from other roads. There exists a road on the north end of Ross Lake – the Silver Skagit Road – and this theoretically allows the public to drive to the lake and launch private motor boats. However, that road was washed out in November 2021 and it is unclear when it will ever reopen. It is possible that the road might be passable to a snowmobile in the winter, and an intriguing option might be to drag a boat behind a snowmobile to access the north end of the lake. I haven’t been able to test this, though, and I’m not sure if it would technically be legal to come in from canada that way if the road is closed and there is no official checkpoint open at the border along the road. There are currently two options to get a personal motor boat to Ross Lake. The first is to carry it down the 0.6-mile trail from the Ross Dam trailhead to Frontage Road, and then take it 0.5 miles down the road to the lake. The other is to put the boat in at the boat launch at Diablo Lake, ride to Frontage Road, then somehow carry or drag the boat up Frontage Road (1.5 miles, 600ft gain). From talking to friends with experience boating I settled on two main options. The first was to use a canoe with an electric outboard motor. This could theoretically be carried down the trail in multiple loads. It could also theoretically be dragged up Frontage road on a dolly, though only if Frontage road were snow-free. However, the canoe has several disadvantages. First, it is not very stable. I have friends who’ve tipped over in canoes on Diablo lake. That would be dangerous in winter, and winter is when the weather is generally worse on Ross Lake. Also, the biggest motors I could find for canoes were electric trolling motors that would struggle to get 15 miles up to Little Beaver, even at a very slow speed. Plus, an electric motor is not as reliable in cold conditions as a gas motor. The zodiac boat’s maiden voyage on Stave Lake during a climb of Mt Judge Howay in BC The other option was a zodiac-style inflatable boat with gas or propane outboard motor. This vessel is much more stable than a canoe and very difficult to tip over. It is made of durable thick material with multiple chambers. It has a much higher capacity than a canoe, and can go much faster and farther with the gas or propane engine. It deflates, so is portable. They even come with retractable wheels that can be deployed to drag the boat along frontage road. This appeared to be the optimal solution. My friend Matt had such a boat and we went on a test trip together in September 2022 in British Columbia to climb Mt Judge Howay (which requires a boat approach up Stave Lake). The boat had a 4-stroke propane motor, which is very clean and reliable and meets the strict environmental requirements for personal motor boats on Ross lake. That trip went well, and I ended up buying the boat from Matt. The boat as a 5 horsepower motor that is about 60 pounds, the boat itself is 70 pounds, and a full 5-gallon propane tank is about 50 pounds. A duffle bag of accessories (wheels, oars, life jackets) weighs about 40 pounds. Each one of these items is manageable to carry, which makes this a good solution. The motor allows the boat to go a max speed of 5.7mph fully loaded, but this is actually a perfect speed for Ross Lake. Taking the boat for a test run on Lake Chelan with my dog Lily, October 2022 Through multiple tests I’ve found that a fully loaded boat and full tank of propane has a range of 40-50 miles. Little Beaver is a 30-mile round-trip journey, so the propane tank is just the right size with a little bit of safety factor. One problem with Ross Lake is that in the winter the lake level drops and submerged tree stumps stick out in seemingly random and unexpected locations. In winter it is likely that boating on Ross Lake to approach Hard Mox will need to be at night, and it is thus dangerous to go too fast in the dark for risk of hitting the stumps. That’s particularly risky in an inflatable vessel. A speed of 5.7mph is slow enough that stumps can most likely be avoided. To make a trip safer, though, I called the Ross Lake resort and had them mail me a map with general stump locations marked. I also found a fishing depth map of the lake and charted a GPS course to follow the deepest section and avoid known stump areas. I would load this track on my GPS watch before boating up Ross Lake in the dark. First test run of the boat in Ross Lake boating to Little Beaver, October 2022 In October 2022 I did the first test run of the boat in Ross Lake. The goal would be a thorough simulation of the entire Winter Hard Mox approach and climb. My friend Ryan Stoddard recommended the Perry Creek approach to Hard Mox based on his approach to the Chilliwacks the previous year. He said the bushwhacking was difficult, but it would give direct access to the south face – west ridge route without requiring a traverse from the ridge of gendarms that might be sketchy in winter. I first wanted to test the Diablo lake + Frontage Road method. Talon joined, and we decided to climb Hard Mox in a weekend. Saturday morning we put in at Diablo Lake, motored through zero-visibility forest fire smoke in the dark, then reached Frontage road. The takeout was tricky to get the boat up the dock, and dragging the boat and gear up Frontage road was very difficult and time consuming, even with the nice deployable wheels. On the summit of Hard Mox in October 2022 with Talon We made good time up Ross Lake moving at 5.7mph, and got to Little Beaver after 2.5 hours on Ross Lake. We then hiked to Perry Creek shelter. To get up Perry Creek I’d seen on an old quad that there used to be a trail up the north and east side of the creek in the 1940s, but it was long-abandoned. Other groups, including Ryans, had followed that side of the creek and it sounded tough. We decided on a different approach. We went straight up the creek, scrambling on boulders on the side. It was actually fun and basically no bushwhacking. Then we hit old growth forest and followed that on the south side of the creek all the way to the edge of treeline. This showed the Perry Creek bushwhack was actually not bad at all! That was valuable information for winter. In the basin below Hard Mox in October 2022 We camped at the basin below Hard Mox, then the next morning climbed up the Perry Glacier. We were unsure if there would be easy passage from the glacier up to meet the standard summer route, but were surprised to find an easy 3rd-class gully connecting to the route. From there we climbed the standard west ridge route, and it was useful to refresh my memory of which of the lower gullies is the correct one (many teams lose time route-finding in that area). We ended up topping out by 9am, then descended all the way back to the boat, rode out, and I got home Monday morning 4:45 am, barely in time to make it to catch a nap before my morning lecture. This scouting trip successfully showed that basecamp could be reached in a single day with the zodiac boat, as hoped for. I also was able to test my new custom offroading headlights with motorcycle battery that I’d velcroed to the front of the boat. This allowed for boating in the dark, which would likely be necessary in winter. Ross Lake was foggy, though, so visibility wasn’t perfect. However, the approach had the one disadvantage that if Frontage road were covered in snow, then dragging the boat up would likely be very difficult. So that approach might not be ideal. Carrying the boat and motor down the trail in late October 2022 Talon had a friend that worked at Ross Dam, but unfortunately they didn’t have anywhere I could store the boat securely for winter access. We contacted the Ross Lake resort, but they didn’t want to store the boat. So, I would have to get it to the lake on my own and store it at home. I next wanted to test the second option to get the boat to Ross Lake, via carrying it down from Ross Dam trailhead. In late October Nick and Talon joined for another mission. My main goal was to test that boat approach, but a secondary bonus goal was to go survey East Fury. I suspected it might be high enough to be a Washington Top 100 peak. To get the boat down the trail I researched different methods hunters use to transport animals on trails. One way is a single-wheeled device with handlebars and a brake, with racks on the side. I bought materials and hatched a design to modify my mountain unicycle into a boat-transporting device. Nick had another idea to strap the boat to his e-bike and wheel it down the trail then use power-assist to wheel it back up. The boat loaded up with survey gear and the new offroading headlights Saturday night we loaded up the bike and strapped the motor to a pack (upside down, since that seemed most stable). Unfortunately the trail was so rocky and uneven that the bike didn’t really work well. We decided that just carrying the gear in multiple trips made the most sense. With a double carry we got all the gear down to Frontage road and inflated the boat. We then slept a few hours back at the truck, then Sunday at midnight dragged the boat and survey equipment down to ross lake. We put in and boated to Big Beaver. We then hiked up to Luna peak with my theodolite and surveyed East Fury (which I discovered is tall enough to be a new WA top 100 peak). We returned to the boat, motored back, dragged it up the road, and double carried back to the truck. Carrying the boat back up the trail From this trip I determined that it is actually a bit faster and easier to get the boat to Ross Lake via the trail than via Diablo Lake. It also works even if Frontage Road is snow covered. So this would be my preferred method to get the boat to Ross Lake. I now had all the pieces in place to mount a winter attempt on Hard Mox. I had figured out an approach that could get me to basecamp in one day in winter, I had verified that the climbing route worked from my planned basecamp, and I had figured out the optimal method to get the boat to and from Ross Lake. Next, it would be a waiting game. I needed many stars to align for a winter Hard Mox trip to be successful, even with all the logistics already worked out. 1. I had to have a partner available on a holiday weekend (my only holiday weekends were MLK day and Presidents day three-day weekends) 2. Weather had to be stable on the Sunday of the weekend, with minimal precipitation 3. Snow had to be stable on the Sunday 4. Wind had to be low for boating on Ross Lake and for keeping snow stable 5. Ross Lake had to be ice-free 6. Snow conditions have to be manageable on skis if skiing 7. The lake level has to be high enough to cover submerged tree stumps if boating at night. Boating up Ross Lake in January 2023 In January 2023 it looked like all stars would align on MLK day weekend. Satellite images had shown ice a half mile south of Little Beaver on the upper end of Ross Lake, but it was forecast to be warm and rainy for the week leading up to the weekend. We expected the ice would melt then, but as a backup we decided we could walk a half-mile along the shore if needed to Little Beaver River, then cross the river one at a time in my packraft, towing it back with paracord or rope. We planned to ski to increase speed. To ensure we knew about up-to-date snow conditions on the route I wrote custom python software to scrape the NWAC avalanche forecast website every evening and send a message with the forecast to my inreach. This would ensure we had the most up-to-date forecast before deciding to go for the summit. Stopped short by ice, January 2023 Saturday morning we successfully got the boat to Ross Lake and boated up, but we discovered that the ice had not melted. We parked the boat on shore a half-mile line-of-sight from Little Beaver, but unfortunately the shore had many impassable cliffs. This was not obvious from the satellite images. We had to bushwhack around the cliffs, then packraft across Little Beaver, and it took us 6 hours to cover just 0.5 miles line-of-sight distance. The next morning we skinned up to Perry Creek shelter, but above that the snow was too icy and crusty for skiing to be safe. Postholing up Perry Creek would be too slow and difficult. Plus, the additional 6-hour deproach to the boat would leave us too short on time. We bailed back to Little Beaver. Crossing Little Beaver with packraft and skis, January 2023 To get back we were able to do what I call belayed packrafting to get around the cliffs in melted-out sections and avoid bushwhacking. The first person would packraft around trailing our climbing rope. Then once around the cliff they would yell and the second person would pull the packraft back, then paddle around the cliff. This way we could inch worm around the cliffs and avoid bushwhacking. We managed to make it safely back to the zodiac and get back to Ross Dam that night. From that trip we learned that the lake absolutely has to be ice-free the whole way in order to attempt the trip. We also decided that snowshoes are a better choice than skis. With snowshoes we wouldn’t really have to care about snow conditions in the Perry Creek basin. Speed might be slower in snowshoes, but it was more likely we could reach the basecamp than with skis. Packrafting back between the cliffs and ice, January 2023 In February it looked like all the stars would align over Presidents Day long weekend. Nick and I decided to try again. This time the satellite images showed no ice on the upper lake. We decided to go with snowshoes. The only marginal star was the weather. It looked like snow and conditions were stable Friday through Saturday late afternoon, but then a storm was supposed to come in. If we could summit and get back below treeline before the storm, we would be ok hiking out in the rain and boating back in stormy conditions. This time we first carried the boat down to Frontage Road Friday night, then slept back at the trailhead. Early Saturday we carried the gear down, inflated the boat, and dragged the boat down the road. We started boating just at sunrise. In February the lake level is lower and more stumps stick out, so it’s more important to boat in the daylight. Days are a bit longer than in January, though, so this is not as big of a problem to wait until sunrise to boat. Successfully reaching Little Beaver, February 2023 We made it all the way to Little Beaver in 2.5 hours, then hiked up to Perry Creek. We were able to bushwhack up Perry Creek in snowshoes. Snow coverage was good, and we could mostly stay in the creek on the lower sections. Once we reached the old growth we made quick progress, reaching basecamp just at sunset. The next morning we left camp at 2:30am following my GPS track from October on my GPS watch. Pit tests showed the snow was stable, though deep, and we made slow progress. By a bit after sunrise we reached the bottom pitch of the route. The wind started increasing then, almost knocking us off balance. Nick led partway up the first pitch, but my route from October was not the best winter route. It had required crossing one sloping slab down low, which was easy in rock shoes but tough in crampons. Bailing on the first pitch when the weather deteriorated, February 2023 Also, it was difficult to find any cracks to stick gear in. Nick tried a few variations, then lowered down. I gave it a go, but couldn’t find gear placements. By then the storm was intensifying and we decided to bail rather than keep trying. We were concerned the increasing wind might start forming dangerous wind slabs down low. Indeed, as we descended the Perry Glacier we triggered a few small slabs. They were no problem, but given a few more hours they would likely get dangerously deeper. We descended all the way down to the trees as it got windier and started raining. We bailed all the way out to Little Beaver that night. The next morning the storm was raging and we started boating out into whitecaps and heavy wind. The boat took on lots of water and I had to navigate through a stump forest in the waves to get to shore and bail it out with my helmet. We then hugged the shore and made it safely back to Ross Lake. Bailing out water with my helmet on the ride back after navigating through a stump forest and heavy wind and waves, February 2023 From that trip we learned that the stars of weather and snow conditions absolutely have to align with the weekend. High wind is not good on Ross Lake, even with a stable zodiac boat. In October 2023 I did one additional test trip on Ross Lake. I bought yellow fog lights to replace the off roading headlights to make it safer to boat at night, when it is usually foggy on Ross Lake. For that trip Matt Lemke and Mike Black joined me to bring survey equipment up Castle peak. We boated up and back in the dark 10-miles up lake, and the new lights worked much better in the fog. This increased my confidence about boating on Ross Lake in the dark on a future Hard Mox attempt. We ended up surveying that Castle peak is over 30ft taller than the quad-surveyed height, so is solidly on the WA top 100 list. In October I started strategizing about how to try for Winter Hard Mox again. With so many stars that needed to align it seemed like relying on only two long weekends the whole winter was not a high chance of success. That only gave two possible summit days all winter. My only longer break was the Christmas-New Years break. I usually leave the country to work on climbing country highpoints during that window, but decided to stick around this year and prioritize a winter hard mox trip. Testing the new yellow fog lights on Ross Lake, October 2023 I would be available for a full week between Dec 26 – Jan 2. In October Nick and I coordinated that we would both be available, and if all stars aligned we’d give Hard Mox another shot. It helped that enough time had passed since our last attempted that we had sort of forgotten all the hardships we’d encountered. That’s always important before attempting a difficult peak again after an unsuccessful attempt. For this third attempt we would try to make further improvements but stick with some methods and gear that had worked before. We would again go by snowshoes, and would carry the boat down from the Ross Dam trailhead. For the boat I would use an aluminum propane tank instead of a steel tank. I had previously gotten myself stranded on Blake Island in Puget sound when the motor wouldn’t start and I had to row back through 5 miles of ocean. I later took the motor to the shop and the issue was that the steel propane tank had rusted on the inside and debris had clogged the fuel system. Hopefully that wouldn’t happen with an aluminum tank. Dragging the boat up Frontage Road, October 2023 For the Perry Glacier we would bring ascent plates. These are small mini-snowshoes that sandwhich between the crampon and boot and are ideal for ascending steep snow slopes where postholing and snowshoeing are inefficient. This would have saved us time on our February ascent. We each machined custom carbon-fiber plates for the trip. For climbing gear, in addition to a single rack of cams and a few pitons and nuts we’d brought before, I’d also bring a set of hexes. I’ve found these can be hammered into icy cracks where cams and pitons won’t stick. Duncan and I had used hexes to protect Forbidden Peak during our winter ascent in January 2021 and they worked very well. We’d also bring a second set of cams up to 2 inches. For technical tools this time I would bring two BD vipers instead of a viper and a venom. The venom is a hybrid with a straight shaft that is good for plunging, but it’s a bit harder to use dry tooling than the curved shaft. The viper is a curved shaft and better for mixed climbing. I decided it was unlikely I’d need to plunge the tool for an anchor. Nick would bring a Beal Escaper device which would allow for full 60m single-strand rope rappels. This would increase efficiency descending. For crampons Nick converted his petzl Lynx to monopoint to make the mixed climbing easier. I intended to convert my Petzl Lynx to monopoint also, but forgot to do that. For boots I would again bring my Olympus Mons 8000m double boots. It’s important on a weeklong winter trip to have a double boot so the liner can be dried out overnight in the sleeping bag. It’s also important to have a built-in supergaiter, since a separate gaiter easily gets frozen with ice and snow and is difficult to deal with. My 8000m boots were a bit overkill with warmth, but those are the only double boot with built in gaiter that I have. Nick had a similar but lighter boot that was a bit more appropriate. For the tent we would bring a modified mega-mid. Nick sewed on special skirts along the edges to anchor down with snow and increase space on the inside. This would be lighter and more spacious than the ultralight 2-man mountaineering tent we’d brought previously. We would each bring vapor barrier liners for our sleeping bags. This would ensure the bags would stay drier than before over multiple nights in potentially wet weather. Nick would bring a dry suit for the boat ride. I already use one every boat ride and it is much warmer and safer than a rain jacket and snow pants in choppy conditions. I would bring a new SUP hand pump for the boat that would make inflation faster. Plus, this would give us a backup pump in case anything went wrong with the primary pump. In the fall we also got a bit more serious about training for mixed climbing. We did a practice trip together dry tool climbing at Wayne’s World crag off I-90, and Nick did a bunch of additional dry tooling sessions. By mid December it looked like the stars might finally align for the trip. December had been unusually warm and satellite images showed Ross Lake ice free. The weather forecast looked favorable and there was a good chance there would be a window of stable snow. Ross Lake was 15ft higher than it had been in January (based on publicly-available USGS height data), so stumps were unlikely to be problematic. The first potential summit window looked like Friday Dec 29. We decided to give ourselves two full days to get in, to give buffer time for having heavier packs with more days of food. Then we’d establish basecamp at upper Perry Creek as before. We’d have three or four potential summit days, then a day to get out. Hard Mox was the top priority, but if we somehow managed to climb it we’d use our other days to climb other Bulgers in the area. To make our plan completely legal we emailed North Cascades National Park and got a permit for the trip. I flew back from visiting family on Dec 25, then Dec 26 spent the day packing and preparing. I took the zodiac boat out for a short test run in Lake Washington and everything worked fine. Finally we were ready to give it another go. Dec 27 Carrying the boat down to Frontage Road, December 2023 (photo by Nick) I picked up Nick in the morning and we drove up to Ross Dam trailhead by 9am. In our first load I carried the boat motor and propane while Nick carried climbing gear. I think it’s important to bring the motor down in the first load since that is the item most likely to get stolen if left unattended at the trailhead. Next I carried the boat while Nick carried remaining boat accessories and climbing gear. We got the full load down efficiently in two hours. Once all the gear was at Frontage road we pumped up the boat, which went twice as fast with the new hand pump as with the old foot pump. I mounted the wheels, mounted the motor, then we loaded all the gear as far back as possible to be as directly over the wheels as possible. Nick rigged up the rope on the front, then we each put the rope over our shoulders and started dragging the boat. We made sure to keep our steps in synch to minimize bouncing of the boat. Dragging the boat down to the lake We soon got the boat towed down to the lake edge. As usual, a truck from one of the resort workers was parked at the edge of the water. Luckily there was just enough space to squeeze the boat around to get to the water edge. There we each changed into dry suits, water shoes, and put on our life jackets. We loaded the sharp objects wrapped up inside packs or duffles. We placed a tarp on the bottom of the boat, loaded two climbing packs and one accessory duffle on top, then wrapped the tarp over everything and bungied it to the boat. This would protect the gear from waves splashing over and filling the boat with water. Starting the motor (photo by Nick) I pushed off in the boat, wading slightly into the water, while Nick went to the nearby dock. I then retracted the wheels and rowed over to pick up Nick. This allowed him to keep his feet dry. He then pushed off, and I rowed a bit deeper into open water. I connected the propane tank, turned the motor to neutral, plugged in my key, pulled out the choke, turned the handle to start, and gave the pull cord a pull. On the fourth pull the motor started, which is really good for starting cold. Usually it starts on the tenth pull. I then depressed the choke and we started off by 11:45am. Boating up lake I went at half speed to the water gate, a small gap in the floating log fence that protects the resort buildings from waves. We found the gate at the far end of the lake, marked by green cones, Once through I cranked the motor to max speed and we cruised along at 5.7mph. I’d gotten pretty familiar with Ross Lake after all the scouting trips and attempts and knew all the landmarks. We cruised around Cougar Island to the east, avoiding the temptation to cut the corner in the gap with the coast, since I’ve found this can be deceptively shallow. We passed close to Roland Point, but not too close since I recalled a few stumps in that area. Taking out at Little Beaver After passing Pumpkin mountain we rounded rainbow point and on to Devils Creek. That’s the site of a big stump forest which was luckily submerged today. From there I crossed to the west side following my memory of the lane of deepest water. We passed tenmile island, which was still an island at this water level, and then passed Lightning Creek, which surprisingly had deeper water coverage than in October. Loaded up and hiking up the trail (photo by Nick) Cat Island was barely an island, and I hugged the west coast. I was careful, though, since I recalled a few rogue stumps across from Cat Island on the west side. This time they were submerged. The only issue we encountered was a big floating log just past Cat Island. That would have been hard to spot at night, but I easily steered around it in the daylight. By 2:15pm we cruised up to Little Beaver Camp. The upper lake was ice-free as expected. The water level was not ideal for docking, though. The regular dock was high and dry, and the lower bench of shore was submerged, so the whole shoreline was kind of steep. We found one boulder that was kind of flat and were able to deploy the boat wheels and drag it up there. We tied it off on a stump, raised the motor, raised one wheel so the boat could rest level, and removed the gear. At the Perry Creek shelter We double carried the gear all up to the Little Beaver Shelter and took a short food break. We then ditched the boat gear in a bear box, packed up our climbing gear, and started up by 3pm. The trail was snow-free so we started hiking in light hiking boots with extra gear strapped on the packs. After three miles we hit deep snow, and switched to double boots and snowshoes as it started to rain lightly. I was happy to have my waterproof hyperlite pack to keep the gear dry. We continued to the shelter shortly after sunset around 5pm. It was very nice to get out of the rain in the shelter and not have to set up the tent. We each threw out bivy sacks and sleeping bags, cooked up some dinner, and were soon asleep. Starting up Perry Creek (photo by Nick) Dec 28 We got up at sunrise the next morning and were moving by 9am. It seemed unwise to be bushwhacking in the dark, so we wanted to be sure to start the bushwhack in the daylight. We ditched our hiking boots in the cabin and proceeded in mountaineering boots and snowshoes. I had loaded my October GPS track on my garmin Fenix 6 watch to help with navigation, but I pretty much remembered the whole route since I’d already done it a few times. From the shelter we stayed on the left side of the creek, and the snow soon got thin enough that we ditched the snowshoes. In general we tried to stay as close to the creek as possible, only bushwhacking around cliffs and waterfalls. Often there are good open lines next to the creek that allow for fast progress. Scrambling up the creek (photo by Nick) This time the creek was flowing much higher than it had been in October, while the snow coverage on the side was much less than it had been in February. This seemed to be a sweet spot that made the creek as difficult to follow as possible. If the flow was lower and the sides drier, it would have been easy to walk on sloping slabs on the side. If the slabs had been covered in a foot of snow, it would also have been easier to walk on them. But this time they were usually covered in a thin sheet of ice. That meant we had to bushwhack around more often than my previous two times. Navigating a slide alder thicket One time the bushwhack around verglassed slabs required crawling up through steep slide alder with slippery mud underneath. I pulled up with my right hand at an awkward angle and slipped in the mud. Immediately I felt a painful pop and realized my shoulder became dislocated. Ever since I dislocated it in the Khumbu Icefall on Mt Everest last spring it’s been more vulnerable, and the heavy pack with awkward fall was enough to pull it out. I howled in pain, but luckily I knew a trick to get it back in on my own. I immediately clasped my hands, relaxed my right arm, and pushed my knee through my clasped hands and pushed. The shoulder popped right back in and the pain soon subsided. It had only been out for about 5 seconds. I vowed to be extra careful going forward with pulling with my right arm. Finally into the old growth forest (photo by Nick) This and a few other detours slowed us down a bit. Higher up we had to pass through one slide alder thicket I hadn’t remembered. I think in October I’d stayed in the creek, and in February it had been covered in snow. That was the only memorably tough section, though. By 3400ft after rounding the corner we hit the old growth forest, which was a welcome relief. I knew it would be smooth sailing from there all the way to basecamp. It had been drizzling all morning and we were both soaked, but at least there would be fewer bushes to brush against in the old growth and our body heat might start drying things out. We ascended steeply up into the forest, and soon the snow got deep enough to warrant snowshoes. From there the woods were nice and open and progress was fast. It was fast until we started having snowshoe issues, though. One by one each of the four snowshoes failed in some way. The metal supports under each of my feet cracked, making the rotating part of the snowshoe detach. I ended up using ski straps to strap the part back on, and the stretchiness in the straps allowed my foot to rotate. First view of Hard Mox (photo by Nick) For Nick almost every individual strap ripped off. He ended up using a long ski strap to strap one foot to the shoe, and some spare cord to tie the other shoe in. I guess this is normal for an expedition to improvise when gear inevitebly fails. Finally we resumed our fast pace through the old growth. I recalled in February we had strayed a bit too high to the south, which forced us into side hilling to maintain elevation. This time I made sure to stay closer to the creek, and the terrain was nice and flat. As we got closer we started looking for a good stick for the middle of the mega mid. Usually on single-night trips I strap to ski poles together for the middle pole. But if we were using the tent as a dedicated basecamp I would want those poles on day climbs. I had a separate carbon fiber pole for the middle support, but wanted to save weight so left it in the truck. Nick managed to find a perfect stick on the way, and we took turns carrying that up through the woods. Basecamp at 4500ft By 6pm we reached the edge of treeline at 4500ft on the edge of the talus field. The snow coverage was much lower than in February, and many more trees and slide alder patches were sticking out. This time the bushwhack took 9 hours instead of the 6 hours it had taken us in February. This slower time was likely because of the unfavorable creek level and snow conditions, necessitating more side bushwhacks. Also the heavy packs, shoulder injury, and broken snowshoes slowed us down. But we successfully reached camp approximately on schedule. We had considered the possibility of pitching camp at 6700ft on the Perry Glacier that night to make summit day shorter. But the snow conditions were not stable that day, and getting up to 6700ft required crossing avy terrain. So we decided to pitch camp at the same place as before at 4500ft. This had the advantage that we knew there would be running water there, which was indeed true. Moving up the next morning We leveled out a spot, mounted the stick, and pitched the mega mid tent. Nick’s skirts on the tent worked great for piling snow on the outside while maintaining space on the inside. We dug out a ditch for our feet and cooked up dinner. At 7pm I got my inreach messages with the updated avy forecast. Friday looked like stable snow conditions and dry weather, as expected. So we decided to go for it. We ideally wanted to get to the base of the rock climbing at sunrise to be able to climb in the light. We expected our speed to be a bit faster than in February with the more consolidate snow and the ascent plates. Also, sunrise was later (8am), so we decided to start up at 4am this time. Dec 29 Looking down to Perry Creek basin It drizzled into the evening but eventually ended. I was unfortunately still wet from the approach hike, and made the unwise decision of putting my wet socks and wet liners in my sleeping bag to dry them out for summit push. This indeed dried them out, but left me damp all night and I ended up getting very little sleep. The 3am alarm came way too early, and we reluctantly started nibbling on bars and getting out of our sleeping bags. The drizzle had stopped, the skies had partially cleared, and a nearly-full moon illuminated the sky almost enough to not need headlamps. This was much better than in February when it had been blowing snow and low visibility as we had ascended. This time was much warmer also, which would be nicer for climbing. On the upper Perry Glacier We were suited up and moving by 4am. I had my October track loaded on my watch, but navigation was easy even without that in the moonlight. The east face of Lemolo loomed above us, with the true summit of Hard Mox just hidden behind. We alternated leads breaking trail in 15-minute shifts up to the cliff below the Perry Glacier, then right into the lower-angle gully. We hiked up some old avy debris that had more consolidated snow underneath. After reaching the first shoulder we hooked left, then found a weakness in the upper steeper slopes. We eventually reached a flat area at the toe of the Perry Glacier. Switching to ascent plates At this point in October I had continued directly up slabs to avoid the glacier, and in February we had continued left onto the glacier with lower angle terrain. This time we decided to avoid glacier travel and ascended right of the slabs. The snow was well-consolidated and travel efficient with the heel risers lifted on the snow shoes. We crested the flat area above the slabs, then ascended higher onto the Perry Glacier. We soon reached a cliff at the top of the glacier and decided to ditch the snowshoes there. It was getting too steep for them to be efficient, so we switched into ascent plates. Looking up at the climb Nick led the way and travel was again very efficient. Each step required only one kick, unlike in February with snowshoes when we had to clear snow with hands, then knees, then double kick to make progress. We made it up the snow gully to the point where the summer route descends and traverses climbers right to the final gully. The terrain got briefly icy, but the ascent plates allow the crampon frontpoints to stick out, so this was not a problem. Nick leading up the first pitch We continued up with our whippets for protection until we reached the based of the first pitch. Here Nick put a cam in a crack, then we clipped in and kicked out a nice platform below the shelter of a rock wall by 10am. Nick is the stronger climber so he took all the gear while I took the pack with a little bit of food, water, and warm clothes. We ditched our remaining gear at the platform and pulled out the technical tools and clipped them to our umbilical cords. The summit was socked in the clouds, but it wasn’t very windy and this time the weather was predicted to improve throughout the day. I always like climbing into improving weather rather than racing to beat a storm that might come in early. Nick at the first crux Nick optimistically started up into the chockstone gully to try to climb directly up. This appeared to be full of ice, which might make it easier than the rock slab. However, he found the ice was hollow and not safe to climb, so backed off. He then climbed directy up the rock wall to the right, where I had climbed in October. He got a piece in down low, then got above the lip, reaching the same highpoint as before. This time he was able to excavate out a crack on the left that took a hex pounded in. That seemed to be the key to getting past this lower crux. He continued up to the bench above the chockstone, and made an anchor slinging horns. Me leading the gully pitch I soon followed, and manged to get decent sticks in thin neve above the lip, and a few good hooks. Of course, I had the advantage of a top rope, so felt much safer. At the anchor Nick handed over the remaining gear and belayed me up the gully. In October I had soloed the gully since it wasn’t too steep or exposed, but in winter it’s fully of ice and you wouldn’t want to fall. It’s kind of long, but not hard, so we decided to simul climb it. I got a few pieces in on each sided, including a good hex hammered in a crack that wouldn’t take a cam. I soon reached the col above and clipped on to the rap anchor at the horn. Nick leading out of the col I belayed Nick up, then handed the gear back over. I recalled the next pitch had been the crux in October, and I was happy Nick was OK leading it. Getting out of the col was a little tricky, and I pushed Nick’s back as he pulled on the lower moves. He got good pieces in going up and right on the face. The next move was to cross over to the right into a gully and ascend. That ended up being the crux. I suppose in summer I’d frictioned up slabby bits in my rock shoes with no problem, but that’s hard in crampons. Nick somehow managed to bang a hex in a crack and excavate out a key micro ledge for the front points. This allowed passage, and he climbed all the way up to the pedestal anchor above. I was yelling out directions from below since I was familiar with the route, having climbed it twice before. Me following the first pitch I followed, and was starting to get a bit nervous about our speed. We really wanted to top out by sunset, but the days were short and sunset was around 4:15pm, which wasn’t too many hours away. So I tried to climb up as fast as possible. Since Nick had already excavated out the good footholds and tool hooks I was able to make fast progress up to the pedestal. The pedestal anchor is kind of awkward since it requires a semi-hanging belay. To increase efficiency we decided to swing leads again. This was kind of nice that I didn’t have to stay at the awkward anchor, but the pitch above looked kind of tricky. I took all the gear and started up. Me leading up the next pitch above the col The rock was interesting since it was all plastered in tiny white rime ice feathers. This made it very slippery, but that wasn’t a problem with crampons and ice tools. I delicately hooked ledges and got a few cams in until I reached a vertical section. There I traversed up and left to a good ledge climbed on top. Above me I could see a nice bench on the ridge, but it looked like an unprotectable slab for 20ft to get to it. I optimistically started digging and clawing around with my tool and luckily found a few cracks under the snow. With cams in I continued up getting good sticks in the neve and hoooking ledges until I reached the bench. I recalled the next rap anchor was just above this bench, but it was a 15ft tall vertical wall that looked tricky. I was running low on gear and Nick was far enough below to not be able to see me there. It seemed like the kind of section where you want good pro and an attentive belayer, so I decided to make an anchor there and bely Nick up. Nick at the pedestal anchor Nick soon climbed up and said he was OK leading the next bit. I told him the anchor was just above, and this should be the last pitch up to the summit. Nick got in three solid pieces on the upper step, then pulled himself over. He made steady progress above that, topping out almost exactly at sunset. Meanwhile, I was admiring the amazing view opening up below me. The clouds were gradually clearing revealing the pickets to the southwest, Easy Mox and Redoubt to the west, and Custer and Rahm to the north. Climbing the last gully to the summit Nick put me on belay and I carefully surmounted the vertical bit. Luckily there were very solid hooks at the top I trusted to pull myself over. I walked past the rap anchor, brushing some snow off, then walked through the low-angle bowl section to the final gully. I was impressed to see nearly every piece of pro was a hex! I had brought six hexes and they all got used on that pitch! And to think, those hexes almost never get used on any other occasion. They really are the right tool for the job in icy cracks, though. Summit panorama I made the final pull over the upper chockstone and reached the summit ridge at 4:35pm. From the anchor it was On the summit a short walk over to the highest little pedstal, which we both did unroped. Our timing was perfect just around sunset with the last rays of sun lighting up the surround peaks, which were passing in and out of thin clouds. That was probably the most scenic time of the whole day. We took turns posing for summit pictures and taking videos and panoramas. It felt amazing to finally reach this point after so many scout trips and failed attempts. I spent a few minutes trying to dig around for the summit register, but couldn’t find it. That’s usually the case in the winter on peaks like this. Nick on the summit After 10 minutes on top we decided to head down. I recalled the main anchor is a small slung boulder on the edge of the cliff that doesn’t inspire much confidence. In October I’d backed it up to a bigger boulder, and saw that was still in place. We backed it up another time and I rapped down first to the next anchor. Nick soon followed by the time it was dark enough to need headlamps. Rapping off the summit At the next anchor I knew a 60m rap would reach the col. We rigged up Nick’s Beal Escaper and planned to do a single-rope 60m rappel. The device is kind of like a chinese finger trap wrapped around the rope. The way it works is once you’re at the bottom you do about 20 pulls and releases, and it gradually releaseas the rope from the trap. I was a little skeptical since I’d never used it before, so I went first and had it backed up. By now the wind really picked up and it was hard to lower the rope down without it blowing away to the side. The rappel is a little awkward to begin with too, since it kind of goes down a ridge. I somehow managed to keep the rope untangled and safely reached the col. I then tugged twice on the rope to make sure it would start passing through the escaper device. Rapping down Nick assessed that conditions were not good for the Beal Escaper to work properly, so he pulled the rope up and made a standard 30m rappel to the pedestal, then another 30m rappel to the col. The wind had really picked up and it was started to get pretty cold, so I was happy when he arrived down safely. At the col we attached the beal escaper and I made a full 60m rap down the gully. I had recalled seeing an intermediate rap anchor on a slung horn, but by the end of the rope I was still 15ft above that anchor. Maybe someone with a 70m rope made that anchor. Luckily I found some cracks in the wall and was able to make an anchor with a few nuts and a girth-hitched constriction. At the col Nick came down and we did 20 pulls and the beal escaper magically released. That was pretty nice to get the full 60m rappel in with the 60m rope and save some time. I next rapped off my anchor and easily reached our platform and gear. It felt great to finally be done with the technical section. Nick followed and did the same trick with the 20 pulls until the beal escaper released. This time, though, the rope got stuck on something just above the chokstone. We tried flicking the rope all directions, and finally pulling down as hard as we could. It was no use, though. The rope was officially stuck. Downclimbing to the snowshoes At that point we had two options. First, one of us could lead back up the lower crux on the other strand of rope and get the top end unstuck, then build another rap anchor and rappel down. That sounded dangerous. It would be tempting to just prussik up the stuck end, but that was also dangerous since we didn’t know how much weight it could bear. Second, we could cut the bottom of the rope off as high as possible and leave the remaining piece. Both of us were planning to return to Hard Mox the coming summer anyway (I wanted to take my differential GPS up to get an accurate elevation reading), so we decided to cut the rope and retrieve the other end in the summer. Descending the Perry Glacier That was the safe decision and felt like the correct decision. So we cut the rope at the middle marker and packed it up. We were soon all packed up and downclimbed back to our snowshoes. We then packed up the snowshoes and continued down our tracks in our crampons. The tracks were nice and visible and not drifted over, which was a good sign that no new wind slabs had formed. We made good progress all the way off the glacier and back down to camp by 10pm for an 18 hour day. Descending the Perry Glacier We checked the latest avy and weather forecast on my inreach and the next day was supposed to be stable snow also, but rain and snow and socked in all day. Sunday was supposed to be better weather, though. So we decided to take a rest day the next day. I definitely needed one anyways. Dec 30 I slept in to 10am, which felt great. It had started drizzling around 3am and would continue on and off throughout the day. Indeed, it looked like a bad day to be above treeline. I stayed drier that night by not putting any wet items in my sleeping bag and diligently staying inside the vapor barrier liner. Rainy rest day in camp We soon discussed objectives for the rest of the trip. Hard Mox had been the primary objective, but we wanted to Resting in the tent tag any other Bulgers nearby that made sense. From the summit of Hard Mox we realized that Redoubt and Easy Mox would be very difficult to access from our camp. We had optimistically hoped to be able to cross over col of the wild to access these peaks. But the glacier north of Hard Mox was heavily crevassed. It looked like steep slabs to gain the col, which had a huge cornice overhanging to the east. That option would not work. The only remaining Bulger accessible from our camp was Spickard. We decided to go for Spickard Sunday, then hike and boat out Monday and Tuesday as originally planned. Rain was supposed to end around 5am, so we would start up at 6am to give a bit of buffer time. Starting up Spickard We spent the rest of the day eating and drying out clothes and socks using body heat. Dec 31 The rain ended as schedule and we were up and moving by 6am. We had planned a route using shaded relief maps to minimize exposure to steep slopes. We took turns breaking trail, and now the once-slushy snow had firmed up with an icy crust on top. This was good news for stability. Good views of Hard Mox We followed the left-most and largest of four snow gullies to our north, soon reaching a low-angle shoulder at 6000ft. From there we traversed right to a big drainage, then hiked up to the toe of the Solitude-Spickard glacier. By then the sun came out and we were treated to great undercast views below. We met up with the standard Spickard route I recalled from my previous ascent, and traversed right on a ledge between two cliff bands to gain the south face of Spickard. Spickard started out socked in the clouds but they gradually cleared and we could see a route up. We ascneded low-angle slopes almost to the ridge, then traversed right below a steeper band. The snow was stable with only a thin unreactive wind slab in a few isolated places. Climbing Spickard Below a small saddle we ditched the snowshoes and switched to ascent plates. From there we easily marched straight up to the saddle, then continued along the ridge until we were blocked by gendarmes. There we noticed a nice snow traverse on the north face. We ditched the ascent plates and got out our ice tools. One by one we traversed the icy face, reaching the summit by noon. The undercast views were amazing, and with no wind and sunshine it was actually kind of pleasant. This was a rare treat to be able to spend more than a few minutes on a winter summit. We took tons of picture and admired the views. On the summit I recalled last year Stu Johnson and Max Bond had climbed Spickard via the NE ridge in what was likely the first winter ascent. I peered over the ridge and it looked way more difficult than what we had done. I think the south face is the easiest way to go in winter if the snow is stable. We soon dropped back down, traversed the north face, and took a food break in the sun on the south side. We downclimbed back to our snowshoes, packed them up, then cramponed back down of the face. We made excellent time retracing our route back down, reaching camp a bit before sunset. It felt great to get both Bulgers bagged from the Perry Creek drainage. I still have four left in the Chiliwacks in winter, but I’ll have to figure out a different way to access those. Summit panorama Leaving camp in the moonlight Jan 1 Our goal was to get all the way back to the trailhead the next day if possible, so we were up and moving by 6am. We made good time following our snowshoe tracks through the old growth, and switched to boots back at the creek at 3400ft. The bushwhack and scramble down went smoothly, and we reached the Perry Creek shelter by 11:30am for a 5.5 hr descent. There we switched into our stashed hiking boots and made fast time back to Little Beaver shelter. Nearing Ross Lake It felt really cold down there, and that may have been associated with the clear weather that day. By 3pm we were bundled up in dry suits and down jackets and soon had the zodiac boat loaded up and pushed off into the lake. For some reason, though, the motor wouldn’t start. I fought with it for 30 minutes before finally giving up. I suspect it was related to the cold. I’ve never taken it out in this cold of temperature, so some possible problems are that the propane was too cold or the motor oil wasn’t rated to the cold temperature. I’m working on debugging that issue still. Trying to get the motor running The boat has a set of oars as a backup, and we started rowing. It would be a 15-mile trip back to Ross Dam and we would try to be efficient. I’d previously packrafted from Little Beaver to Ross Dam and that had taken all day, even with a tail wind. This time luckily the wind was calm, though generally it comes from the south in the evening on Ross Lake. The zodiac oars seemed more efficient than packraft paddles, luckily. We measured that pulling hard and fast we could get up to 3.5 mph, but pulling at a comfortable pace was closer to 2mph. Broken oar lock fixed with bungee cord We took 10-15 minute shifts, rotating out when the person in the bow got too cold. Every shift I would play around with the motor trying to get it to start. We even dunked the propane tank in the water to try to warm it up, but that didn’t work. It soon got dark and we were paddling by starlight. Our strategy was the person in front would give directions until the heading was appropriate, while the roarer would pick a point in the distance to the north and keep the back of the boat pointed at that to maintain heading. Back at Ross Dam When we were near Rainbow Point, a bit over halfway, one of the oarlocks broke so that the paddle was no longer connected to the boat. This looked like bad news. It would be very tough and slow to row out with just one paddle, or even to detach both paddles and row out like a canoe. The oar orientation was way more efficient. Luckily I was able to jerry rig a solution with bungy cords to reconnect the oar to the boat, and we continued on at our normal speed. By 11:45pm we finally reached the takeout at Ross Dam. We pulled the boat out of the water, deployed the wheels, and dragged it up Frontage road. From there Nick immediately took a load of climbing gear up while I packed up the boat and motor. I then hiked up with the boat. Nick came down and got my climbing pack and the propane tank while I returned to get the motor. Finally, Nick made one more trip to get the boat accessories. So it was a 2.5-carry up while it had been a double carry down. I think if the propane tank had been empty as it would have been if the motor had worked, we could have gotten it up more easily in a double carry. By 3am we were loaded up back at the truck. We slept a few hours until sunrise, then drove back to Seattle. 62/100 Winter Bulgers Movie of the trip: Gear Notes: Technical tools, double rack to 2in, hexes (very useful), pitons (unused), 1 stubby screw (unused), ascent plates, zodiac boat, dry suit, double boots, NWAC-scraping-to-inreach python script, beal escaper, single 60m rope, avy gear Approach Notes: Carry boat to Ross Lake, boat to Little Beaver, hike to Perry Creek shelter, bushwhack up Perry creek17 points

-