Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 03/16/18 in all areas

-

No matter where one stands on the issue of risk, this thread is an important and necessary conversation for climbers of all ages and skills. Like many climbers, I believe, my relationship and outlook on risk versus reward in climbing has been complicated from the very beginning. That relationship spans 26 years, more than half of my life. My view of risk has had many faces through the years, and it continues to be complex and fraught with contradictions. Which it should, if we are being honest with ourselves and continuing to play the game for the longhaul. Perhaps the most consistent element of it for me is that even in my younger age when I thought myself more 'bulletproof', I've always gone into every serious alpine climb with a very clear-eyed attitude as to the danger I was willingly embracing. "I could die on this trip", is something I silently recited to myself, as the plane lifted off in Talkeetna, or I stepped off the pavement in El Chalten, or I began traipsing up some Rockies drainage towards my objective. While just verbalizing these words didn't change the objective risks I would be facing, it allowed me to proceed with commitment and decisiveness into that zone, and to fully accept the potential consequences. It also served as a reminder of the responsibilities I had at home, the responsibility I had to get back home, which means that aforementioned commitment was not without conditions or limits. I don't regret any of the adventures I've undertaken over the years, nor my lifelong commitment to climbing. Yet in some respect, today I have an increasingly difficult time reconciling my desire to celebrate these memories, with a nagging question of why I have survived, when so many others I knew have not. My wife and I never had children, but I know that if we had, I would have done much less than I have. My wife is a saint for having tolerated so much time away, so much of our money spent, and so much worry that I have subjected her to, in what has been inarguably a selfish pursuit. We have been able to navigate it successfully out of a mutual recognition that a passion for something is what makes a person who they are. I think she has been simultaneously admiring of and appalled by my dedication. I became friends with Marc Leclerc a few years ago in Patagonia, where we shared a number of dinners and trips to Domo Blanco together. He seemed an astonishing soul to me, and someone who was extremely kind, humble and unassuming, especially considering the wavelength on which he was operating in his climbs. When I have observed some of the achievements and risks that he and others like him have taken, I am certainly impressed by the athleticism and the mind control they exhibit. And I've also just shaken my head in a manner that represents neither condemnation nor unbridled approval, but rather, an honest acknowledgement that these sorts of achievements are so far outside of my own abilities and comfort zones that I simply don't understand what they are. It is almost as though I'm watching an entirely different sport. It's tempting to frown on extreme risks, and yet as I myself have taken more than my own share, I'm not in a strong position to judge. In fact, I think we must recognize that their propensity and ability to take such risks is an intrinsic part of their character, the very thing for which we love those of this group that we know personally. And so if Bob's concern about applauding high risk has any merit- and I think that it does- I think it's that the community needs to be brutally honest with themselves about what we are witnessing, even if we choose to admire it. The brutal and honest truth for me is that I have ceased to even feel shock, much less surprise, by each one of these successive tragedies. Ryan, in fact was a good friend. Last fall as we unsuccessfully tried to synch up for some rock climbing in the Cascades, he glowingly told me how he didn't want to be away from his 2 year old son for very long, and that he no longer needed climbing to fill a void in his life. So heartbreaking to think back on this exchange now. But I fear that I've become so accustomed to these accidents as to be desensitized, out of a simple need to protect myself from a total meltdown. I have a photo from my own wedding, in 2006. In it, Lisa and I are surrounded by 7 of my closest friends. Three of them have since died in the mountains. A photo from one of the happiest days of my life now causes pain. Amidst the deaths of numerous casual friends through the years, the loss of Lara Kellogg, Joe Puryear, and Chad Kellogg, leaves a hole in my heart that can't ever be repaired. The widespread wreckage left behind from incidents like these can't be understated. A friend of mine here in Alaska who used to do some cutting edge stuff likes to remind me of why he scaled back the big alpine. "My wife says, you won't care when you’re gone, but I will". The losses that have touched me, my work commitments, being well over 40, and most recently, having a serious illness have all conspired to blunt the sharp edge of my formerly insatiable motivation for the mountains and big adventures. And yet I still do it, and I still hold ambitions on which I plan to execute in the near future. Amidst the flood of mixed emotions and out of a cloud of darkness, certain things have become clear. Two years ago, I was diagnosed with the ultra rare and very lethal adrenal cortical cancer. At the time, I thought that if I somehow survived it, getting a second chance on life, I could never justify taking serious risks for recreation anymore. Two years, two major surgeries, and a month of radiation treatments later, I'm somehow not only still here but cancer free, and throughout much of this time, I've been able to climb at full speed. I have so far gotten off easy. But I've deep dived into the world of this disease and what I've seen is neither pretty nor dignified. And I'm not out of the woods by a longshot. I know who I am and what has taken me to this point in my life. I've wrestled over and over again with how sustainable this activity is. I've simultaneously envied those like Marc who at a young age had the vision and heart to become committed in every fiber of his being to climbing mountains, and also had the talent to be one of the very best; but also guys like Simon McCartney, who at age 24, with Jack Roberts, established the hardest route ever done on Denali at the time, the massive southwest face. It was the zenith of what had been a meteoric few years of serious and groundbreaking alpine ascents for him. But high on this climb, Simon nearly succumbed to altitude illness in a harrowing ordeal, and afterwards, quit climbing cold turkey, moved to Australia, got married and started a successful business. Simon told me: "I knew what I needed from climbing at the time, each climb had to be harder and more audacious than the next. I could see exactly how that was going to end. I didn't want to die, not at that age". Simon is now 62 and has had a happy life. I've come to realize that as long as I have a chance of dying of cancer, and that if I could choose the manner of my death between that or climbing, I'll take the mountains. Ultimately, between the all or nothing of the above examples, I hope to walk a fine line right down the middle on my way out of this life, whenever and however that happens. Onward, and upward-5 points

-

2 points

-

I love discussions like this. Maybe I'm missing it but It seems that everyone is assuming death as a result of high risk acceptance. Of course that isn't always the case, and in fact in the majority of accidents, injury due to high risk is the more likely result. The more important question is whether you can live with the results of your decisions if you don't die but instead have lifelong debilitating injury? Quinn Brett I don't know Quinn, but she seems like an amazing athlete and even more amazing person. But she took big risks and it went wrong. In my own personal risk assessment when climbing and skiing I worry more about not dieing than dieing.1 point

-

FWIW, I don't have any metrics on my personal web site and I don't have any ads. Never have. Primarily for two reasons: To resist the temptation to make it about popularity and to keep my motivations more grounded (i.e. not about money). I've been asked to write for money and declined, for the same reasons. I've seen Ed Viesturs talk. I walked out thinking, "That was boring". And compared to someone like Twight, what Ed has to say decidedly lacks drama. If shit looked or felt bad, he went home. And you're right: That crew tends to live longer in more obscurity. Is there a right or wrong option? Not in my opinion. Just choices with consequences. Jberg and Willis Wall. I'd looked up at both for a long, long time. Started dreaming of Willis when I read about the "Traverse of Angels" in Beckey. It sounded like a place I wanted to be. The Jberg route...to spend that much time moving across terrain entirely untraveled by other humans. After just three of them, I can so easily see why Fred became obsessed with FAs; it's as different an experience for me as gym vs. alpine climbing. No guide book, no topo, no route description, no looking for tat or cairns or rap stations or anything. An entire category of distraction from just being in the place in the moment falls away. My ego did revel in the sharing of what we'd done, yes. And, I don't recall ever thinking "I can't wait to get back and tell people about this" when on-route. "Spraying" wasn't a motivation that I recall. Before JBerg I told exactly one other climber what we were trying, in case we went overdue. Same with WW. And, whether it's a Grade V alpine FA, or an off-trail Alpine Lakes traverse, or a day of off-trail scrambling/canyoneering in the Valley of Fire (all of which I've done with thorough enjoyment), there is just something, for me, more pure and magical about being in a much-less peopled place; finding my own way, and making it up as we go with a fantastic partner.1 point

-

My experience is that the avalanche reports aren't all that accurate. I've been surprised several times when I shouldn't have been, if you had believed the report. Therein lies the problem. The data you're trying to use to come up with your risk calculation isn't at all precise, but you're treating it like a point value. I'm not talking about either extreme of the scale, which is often pretty accurate, but the middle ground where several avalanche professionals die each year. It's not a simple math equation you can stake your life on.1 point

-

In an ideal world this would have been posted on the sites anniversary, Oct. 2, which would have been 17 years in existence. Also ideally this would have been posted three plus years prior when I first started working on the migration. We actually started talking about it much further back. Something I’ve learned is things don’t always work out like you planned, you just have to keep moving forward and learn from you past mistakes. I’d like to thank those who are still around, some of you who have been here from the beginning. I’m sorry to those of you who have given so much to this site in the form of great discussion and trip reports, to the moderators that dealt with so much of the not so great moments, and that I let you down in not keeping this place working better and in a more modern state. We'll make it up to you. Porter, thanks for helping keeping the stoke alive with me and being such an amazing friend. Trip Report Tool v1 I’ve got the new trip report search working. In some ways is a few steps back from the old search in that you can’t facet by month or forum. It’s a step forward in that it works and works well on mobile. http://cascadeclimbers.com/forum/tripreport This only works if you are logged in at the moment. This wasn’t by design just what happened as I added this on the work of the developer I hired who did the TR submission work. We’ll get that sorted out. What we have on deck will be polishing up some of the trip reports and probably adding better geographical data for being able to search trips on a map. We certainly view trip reports on this site as our crown jewel, we are just shy of 9000, and we’d like to make sure they are easy to find and easy to add. I think we’ve nailed the later with the forum upgrade and I’m confident we can come up with better search. The Future Like I said we have now been in existence for 17 years. Not many things on the internet can claim that. But the upgrade of the forum and the work we are doing now is the beginning and not the end. I was 24 when I started this site and really didn’t know a whole lot. I was trained as a biologist and had no experience or really knowledge of web communities. My (still) good friend Timmy and I just decided to create something. I’ll never forget an email I sent to a pretty notable local climber when we first started. I actually don’t remember what I asked him, but I remember his response “Good luck getting traffic, that will be hard”. He seemed pretty pessimistic, but he couldn’t have been more wrong. Getting the traffic ended up being easy, managing it was the hard part. There were certainly some real wild west early days with cc.com and it was difficult to know how to handle them, especially our spare time for what was a hobby. We’ve made mistakes. We can acknowledge that. And we have learned from them. There are people and behaviors that will no longer be welcome here. What is sad is many of those people just took their dump and left. I realize we have a bad rep with many people and that’s unfortunate. I also think it is what you make it, and maybe it’s time to give it second chance and be part of the solution. We’ve solicited a lot of feedback, we’ve read feedback posted on Facebook. We’ve taken a lot of it to heart. I understand Facebook is easier to use, they are a multi-billion dollar company with scientists who’s sole purpose is to get you hooked. I get that Mountain Project is a nice tool, I have nothing negative to say about them, but again they are owned by REI now and have huge coffers of money. It was also incredible to read how people met their climbing partners here, or even their partners in life. Yes there has been some bullshit, but there has also been a lot of good. Cascadeclimbers is a unique and local product: an opportunity to interact online as a community rather than as the product. We are not here harvesting you and your information. This is still a hobby for us. We turn down offers every year to sell this site as we know it’s not in it’s best interest, we know what will happen if a corporation take it over. We have turned down advertisers because we have stayed true to our commitment to supporting retailers. We run the site, we own the site, but the content belongs to the community. We will be better stewards of this place and we hope people will give it a second chance. To those sitting on the sidelines, sometimes reading, but not participating. I get that you don’t want deal with the spray, and I assure you things will be different forward. But I also challenge you because the only way to make something better is to make those positive contributions. If everyone just steps away because they don’t like certain things then all you are left with is what people don’t like. This is a community driven site and only works with contributions from the community. We will be better listeners and stewards; please be better contributors. Why we allow anonymity. This is actually pretty simple; we have no way to prove someone’s identity. Facebook doesn’t either. We also made this decision pretty early on because we felt this would make it a safer place for women to contribute, without a bunch of guys stalking them. Again keep in mind these decisions were made 17 years ago, but I still think it’s a valid point. We recently added JasonG to the moderator staff. You probably already know Jason from his Trip Reports and amazing photography. We are always on the lookout for trusted and committed people to help the site grow, so let us know if you are interested. We may have more roles in the future that need filling. And of course a huge thanks to all the existing moderators that have stuck with us through thick and thin. Our current path forward is pretty simple: We expect people to leave things better than you found it. If you can do that simple things you can be a part of this. If you can’t you will not be welcome here. We want the site to grow, in people, in posts, in trip reports, and new personal connections. Thanks for reading. Onward.1 point

-

@Joe_Poulton I agree, which is why this thread is separate from the one about Marc and Ryan. It's natural for people to want to talk about risk, but this is not a critique of those guys, its a separate thread where folks talk about their own relationship to risk and climbing. We're actively trying to avoid the sort of muddle that's currently going on in the Supertopo forum thread about Marc and Ryan.1 point

-

The basic idea is that for avalanche risk, you have a hazard rating (H = 1-5 = Low-Extreme). That rating sets a base line hazard for the day. Then you can take steps to reduce your exposure to that hazard (lower angle slopes, avoiding N aspects / problem aspects, controlling group size and travel habits). The steps are given a corresponding reduction factor RF. The equation is risk R=2^H/(product(RF)). At R=1, you get to the 1/100,000 likelihood of dying on that tour. At R=2, 1/50,000, and so on. The table in your link does a good job of distilling those daily odds into lifetime likelihood based on ski days / year. So, if you like the idea of having a 99/100 chance of not dying in an avalanche in your life, and you ski 20 days a year, and you plan to ski for 50 years, you need to average R=1. If you think you have a 99/100 chance of not dying in an avalanche, but you run some quick calcs and see that you are averaging say R=3, it might be time to revisit your basic big picture behaviors. I like the simplicity of the tool for pointing out how a rather trivial decision can quantitatively affect the risk you expose your self to. For example, how much more dangerous is it to always ski 37 deg terrain vs 33 deg terrain - turns out its a factor of 2. What does group size do to risk? I don't calculate a munter risk for every tour, but I do think a lot about how it is the accumulation of risky behavior that catches up with us, not a single risky decision. I try to be honest about the risk I expose myself to, and I try to honestly assess what risk I am willing to accept. In skiing, most of the time you will get away with bad decisions, so having a statistical framework around decision making, rather than waiting on bad consequences from your bad decisions can be helpful. I think rock climbing is quite a bit different. For R/X trad or free solo we generally go into it with a strong sense of technical ability and likelihood of success based on well protected climbs performed in the past. For example, what's the likelihood I'll fail on a 5.4, 5.6, 5.8, etc. Am I comfortable soloing or running it out given what I think those odds are? What if I'm off by a factor of 10, is that still acceptable risk to me? In contrast, if I tried to solo 5.14, there would be a 100 % risk of failure. Alpine climbing gets more complicated. There is no simple avy report for alpine climbing. And as I complained above, there isn't really great data that breaks down the risk factors (beyond say 8000 m peaks vs not). So instead, you get the gut feelings about risk exposure described above.1 point

-

But are any of you going to stop alpine climbing because of some back of the envelope calculation? I won't at least. The estimates of risk for any outing/route on any given day are wild SWAGs, at best, and quite unconvincing for me to give up something that has provided so much color to my life. Too many variables, too little data. For sure I've dialed back the "risk" or whatever over the years, but I think I'm mostly just deluding myself. Watching my old relatives linger and die over the years convinces me that no end is great, so I may as well enjoy it. My family wouldn't be that surprised, including my kids. I've had enough partners die and been involved in mountain rescue long enough that death isn't an uncommon topic in our house. I think the bigger issue is whether or not you believe this life is all there is. The spiritual dimension is much more compelling than statistics, at least to me. When it is your time, it is your time. Death is coming for us all.1 point

-

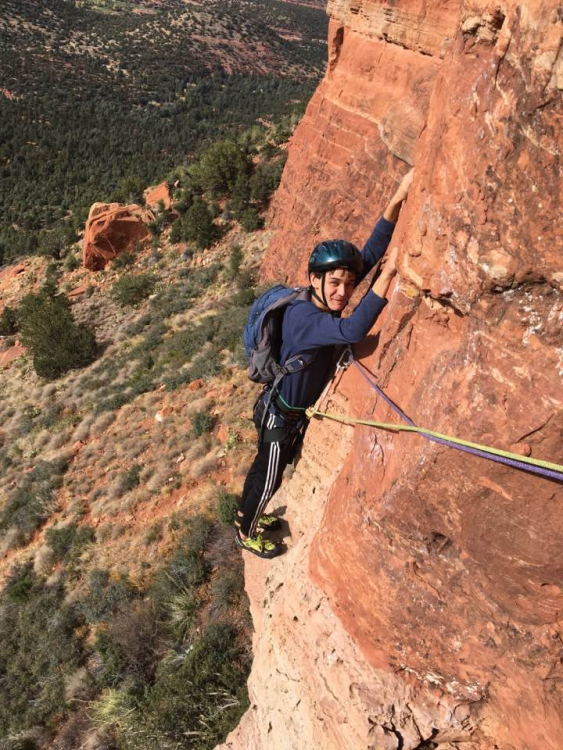

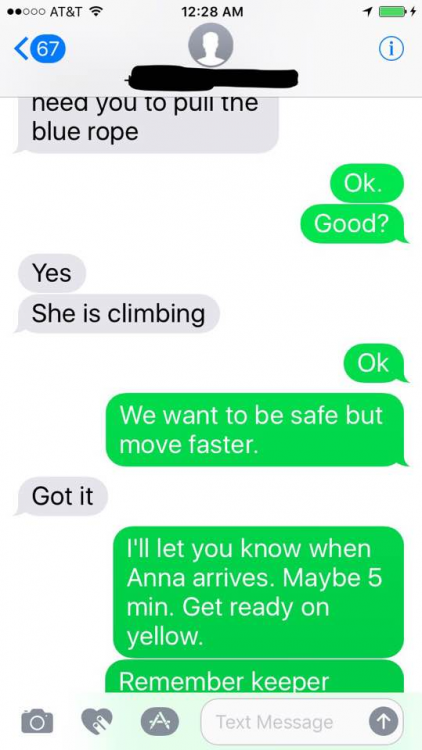

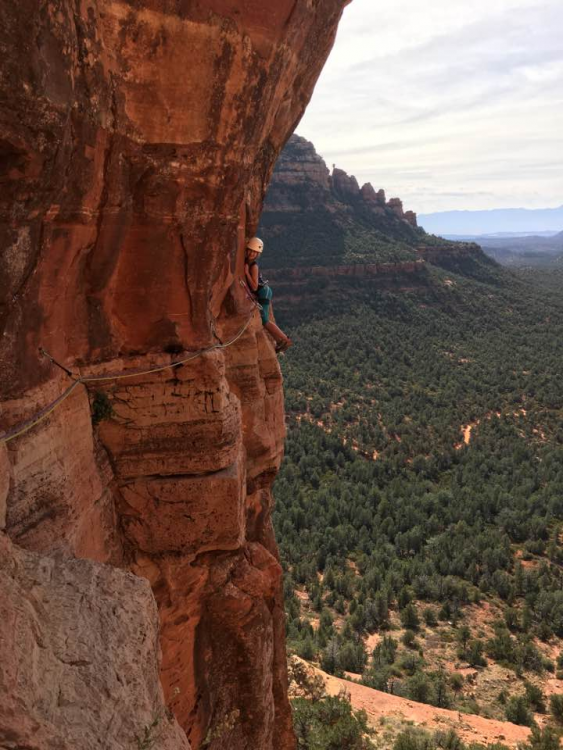

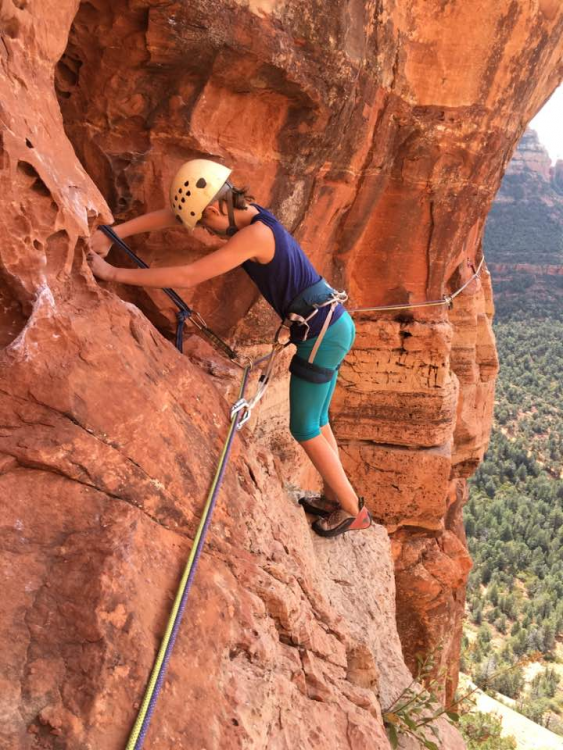

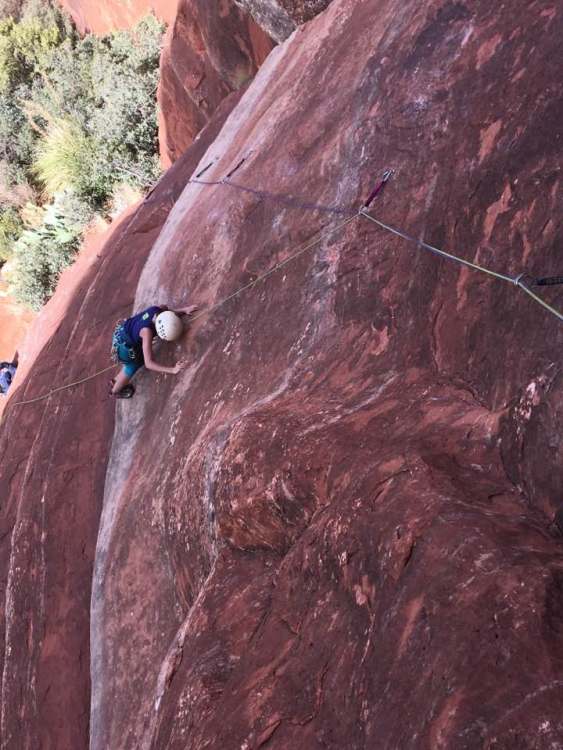

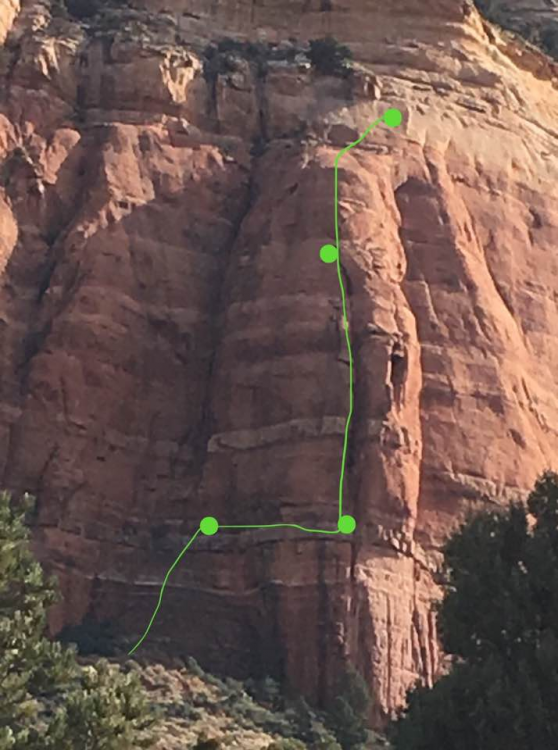

Trip: Sedona - Mars Attacks! Trip Date: 11/20/2017 Trip Report: Having an adventure that pushes you beyond your comfort zone is great....unless it's your daughter, a friend's child, and your wife on the other end of the rope when things go sideways. When my wife and I started dating we made a deal: I’d learn snowboarding, which she loves, and she’d learn climbing, my passion. We shared some good times on the rock many years ago, but in recent years we haven’t climbed together except in the gym. My daughter, now 12, started climbing early, but she’s only been outdoors a few times, on top rope or following single rope pitch bolted climbs. Dan, a close family friend, has really enjoyed the few times he’s climbed and was eager to do more. A quick trip to Arizona, a few hours from his family, provided an opportunity. I figured we’d just climb on some short, easy routes in the sunshine. I’d walk to the top, set up an anchor, toss down the rope, and belay. But then on our hike to Devil’s Bridge we saw climbers on a sun-drenched buttress across the valley. Gaping from flatland, I realized I was now the tourist gazing up at climbers instead of the climber looking down on tourists. I’m not ready to make that transition. So I did some research and looked up the route…. The climb we did is the prominent buttress in the upper center of this shot. It was Mars Attacks. Four pitches of 5.8. Each one holds a different mental and physical challenge. 400 feet of climbing with a traverse and two double-rope rappels to get off the top. I might be pushing too many envelopes at once by bringing three inexperienced climbers up the route, but I was confident I could get us safely up and down (green dots mark the belay stances at the top of a pitch.) … The approach started on the familiar trail to Devil's Bridge before heading North to a wash and a faint climber's trail around a cliff to the base of the wall. Somewhere in there we got off route and had to dodge some ankle-biting cacti, but we found our way... The trail contoured above a small cliff with great views back across the canyon... At the base of the wall, we got our gear together: two ropes, harnesses, and a variety of climbing gear. My daughter sticks to the wall even without her climbing shoes. The crux of the opening pitch is a holdless low-angled slab where you must trust your feet and the rubber in your shoes, balance on the balls of your feet with no handholds at all, and BELIEVE in order to climb. I lead the first pitch, scampering up moderate climbing to a high first bolt. 20 feet later I hit the crux slab. I puzzled for a bit, but hundreds of ascents in recent years have worn off the tiny features on the rock, which is now smooth and blank. I tried one sequence and started sliding, so I grabbed the protection to stop. We didn’t have all day, so I pulled on the quickdraw and stood on a bolt to get past the crux. I climbed the rest of the pitch clean and made it to the belay, an airy stance below a giant hueco. The others came up behind me, with a bit of tension on the rope to help them through the crux. They all did great on the rest of the pitch. At the belay there was a giant hueco worn into the rock by thousands of years of desert winds. It was a comfy spot for some to take off their shoes and take in the view. The second pitch is a horizontal traverse along a limestone dike in the middle of the red sandstone cliff. There are good holds most of the way, but the exposure is incredible. The limestone band protrudes from the cliff because the softer sandstone below it eroded away, leaving you staring down between your toes to the ground about a 100 feet below. If you fall, you will dangle in open space and might be unable to re-gain the limestone. I had a hard time sleeping the night before the climb, going over in my mind how we could all safely climb this pitch without risking a pendulum fall into space. First, I lead across. A came next, clipped to both ropes via slings but not tied into either one. Via ferrata style. She had to unclip one sling at a time to get around each bolt. If she fell she'd still be attached to both ropes and could easily get back on the wall. Here she is moving past one of the seven protection bolts that were placed by the first ascent party in 2000. Resting in a thin section. The Devil's Bridge trail is visible behind her. It was impossible to communicate on the second and third pitches, but we had just enough cell signal for texting. Here's a snapshot of our communication. We had a clear plan, and I knew Beth had enough climbing experience to belay me and make sure A and Dan could set off safely. Arriving at the end of the limestone band. Dan coming across second. He was tied into the end of the yellow rope and had one leash clipped to the blue rope, which would keep him from dangling in space if he fell. He didn't. Beth came last, tied into the end of the blue rope. She unclipped our gear from the bolts. She was totally solid and didn't fall. Two pitches down. Two to go. But we were moving slowly. I was having to check everything and do all of the work to keep the ropes and protection organized and untangled. We were always very safe, but we were slow. And it would catch up to us... The third pitch is a dark red vertical chasm, a slot, like an open book. The steep sandstone on one side of the corner has been worn by wind into crazy pockets called huecos. Some are tiny, others are large enough to climb into, and you’ll find every size in between. Then there is the crack, which varies between the width of a finger and a slot several feet wide. To ascend you must use a wide range of crack climbing techniques that are not very intuitive to the uninitiated, including hand and foot jamming, palming smooth walls to move your feet up in a stem, using your palm and upper arm in opposition while your arm is bent like a chicken wing in a wide crack, lie backing on a sloping rail, and more. I placed cams at wide intervals for efficiency and because I didn't have a lot of gear. Fortunately, the climbing wasn't too hard and the tough bits were well protected. Sometimes an accidental shot can yield an interesting image. This is looking back down from high on the third pitch. Lead climbing brings the mind into sharp focus. The world's deluge of distractions is swept away in the face of the immediate situation. The views from high on the wall were stunning, the air was still. At one point, a raven swirled on rising currents and circled our group curiously, wondering what these noisy, vulgar beasts, whose brethren provide such rich garbage down below, were doing up here in the land of wind and stone. The fourth pitch combines some awkward crack with slab and face moves and ends with a long, unprotected section of low angled rock where a fall by the leader is unlikely but would be bad. Dan climbed the final section of the final pitch... just as the sun was just about to head down below the horizon. Night would soon be upon us, and we still had to get down. Here we are about to make the first rappel, which runs down a clean face on the far side of the buttress. You can see the trail far down below us. I rigged everyone's rappels and then headed down first to look for the next bolt station just as the sky glowed orange and red in a beautiful sunset. But we didn't have any headlamps, a cardinal sin I acknowledged before we left the car in the morning. I've rappelled in the dark, but never without a headlamp, and I've never had inexperienced climbers rappel in the dark without a light. Good thing they're all strong of mind. I rappelled down the vertical face in gathering darkness, looking for a three bolt anchor mentioned in the guide. We'd never seen this part of the wall as it's on the other side of the buttress we climbed. And here's where I pushed things a bit farther than I'd intended, because I never found the bolts. I looked left and right between 45 meters to 55 meters down our 60 meter ropes. Nothing. Swinging back and forth across a blank cliff in near darkness without a light was a bit unnerving even for me. Our ropes wouldn't reach the ground, and although I could have ascended back up to our anchor above, it would have been very slow and difficult. We could have rappelled back down pitches 4 and 3 and then to the ground from there, but I'd read multiple stories of people getting their ropes stuck in the cracks we'd climbed, so that was surely a last resort. Instead, I swung over to the crack shown here and built an anchor using a few cams I just happened to still have on my harness. Truth be told. I'd put most of the rack in the pack my wife was carrying. Fortunately, I had the pieces I needed. Luck was with us. I clipped myself into this unplanned, makeshift belay spot and yelled off rappel so the others could come down to me. I held the rope ends as first A, then Dan, then Beth rappelled down in the dark to join me in this corner crack 150 feet off the ground. I pulled them each over to me from the blank face out right. We were safe, and I kept reminding them of this. The stars came out on a brilliant night. I was able to tuck my phone into my pants by my belly and shine light on our belay as we rigged to descend. This time I would just lower them one at a time to the ground. Thankfully, the rope reached. I lowered Beth into the darkness first, explaining that she'd need to climb up to the large ledge below us if the ropes didn't reach the ground. But she made it. We were safe, but well beyond our intended plans. Then again, that's where adventure begins. We made it down and used the light of my phone to hike out on the trail. The evening was calm and still and the Milky Way guided us back to the car. I ended up leaving two cams behind. Over the years I've gathered gear from the misadventures of other climbers. This time they can benefit from ours. No worries. An adventure to remember! Gear Notes: Headlamp would've been nice Approach Notes: Follow the trail1 point

-

You are the person who has judged, I guess. It might be more accurate to say "Too much objective hazard for me". I would much rather be dependent on my speed and skills to get through that threatened slab section on Jberg than be stuck under a clusterfuck of bumblers knocking shit (and themselves) down on me on the Cleaver or below the Pearly Gates. Similarly, I fret less climbing up the Haystack Gully in thin, difficult ice conditions in winter than I do in summer when the hordes are sketching about above me. Only two people fully understand the risk on the Jberg route. Both measured it against their abilities and chose to proceed. To this day anyone else passing judgement on it is doing so with incomplete info. It's no different than big-mouth Krakauer writing a book about the 96 Everest disaster from the perspective of someone at sea level- the frame of metrics is just wrong. I've been in situations where I needed something from the lid of my pack and, as Beck Weathers said about his gloves, it might as well have been on the moon. "He should have just stopped and put on gloves" might make 100% sense at sea level, but at 28,000 feet or, as was my case, in 100+ MPH wind, it's nonsense. Thousands of people a year spend about the same amount of time under the Ingraham Icefall, where Peter Whitaker and team nearly got the chop, as we spent on those slabs. There is a trench-path below the icefall and with it comes a false sense of security. That said, Jens' (Klubberud, not Holsten) description in the TR he posted is more dramatic than I recall and than what I wrote for my TR and the AAJ article. My Dad came home from work in April of 2000, went for a run like he did almost every day, and then fell over dead at the kitchen sink from a heart attack. He didn't even have time to turn off the water or call out to my Mom, who was asleep one room away. Another friend had both his parents killed and his wife and newborn kid severely injured by a drunk driver as they stood at a crosswalk in Seattle. The only guarantee in life is death. In the mean time, I try to make conscious, reasoned, internally-referenced choices and refrain from judging the risks other take.1 point

-

First off. No offense taken Bill!! All good man, all good. Thx for pulling me in here I know my answer is kinda simplistic, but for me, this viewpoint helps me understand my decisions about pursuing climbing. I don’t want any illusions. For me, they are a disservice. I really think it’s important to recognize my fragile mortality everyday. I think it’s important to be grateful everyday for health, love, and happiness. Step three is to get out there and do what you love while trying to stay as safe as possible. But like I said above, there are things I don’t understand. I don’t think any of us would ever want our climbing friends to not follow their dreams (maybe I’m wrong?), but the pain is nearly unbearable when a friend is lost. Sometimes our actions in the wake of an accident may seem desperate and that’s ok. We are only human. When a close friend dies your heart may shatter into a million pieces. I’ve come to believe it’s about gathering the pieces that were scattered and putting yourself together again. The pieces won’t fit together quite the same way and that’s ok. Give yourself time (lots of time!) and keep inching forward. Reach out to the people who love you and let them support you. This is all I got after losing friends to both sickness and mountain accidents. I watched my mother die of cancer and Chad died by my side in a horrific accident on Fitz Roy. Both deaths were very traumatic for me and understanding how I can continue living and loving has been the theme of my life the past 10 years. It’s been beyond hard, but I’m as happy as I’ve ever been. I love myself and I’m learning to own my story. It is a wild journey. Sorry to take this thread a different direction. For me, I’ve been concerned about the boys in AK and I’ve applauded their climbing over the years too. As a lifelong climber still dedicated to the game, this seems totally natural to me. Just my take on it!1 point

-

I think most of us solo 3rd to 4th class rock at times, or get on steep snow etc .Often enough on poor quality rock or soft snow etc . At some level there is no “them” and “us” it is only us. Even just hikers get on sketchy ground. Best wishes and a prayer.1 point

-

Plenty of bad ass climbers have died in car accidents. I am still holding out hope for these two, but as the days pass... Easy to judge the climbers. Decisions have consequences. I feel really bad for their friends and families.1 point

-

reckon marc woulda been doing what he was doing regardless of public applause - in the big picture, celebrating daring climbers isn't nearly as impactful as celebrating, say, football players...1 point

-

From LeClerc's blog on his Emperor Face ascent on Mt Robson: "It was now my fourth day alone in the mountains and my thoughts had reached a depth and clarity that I had never before experienced. The magic was real. I thought to myself that the essence of alpinism lies in true adventure. I was deeply content that I had not carried a watch with me to keep time, as the obsession with time and speed is in fact one of the greatest detractors from the alpine experience. I was happy that my entire experience had been onsight, on my first visit to the mountain, and that the route had been in completely virgin condition. One of the greatest challenges of mountaineering is in dealing with the natural obstacles the mountain provides. So often in modern alpinism, routes will be fearsomely difficult for the first party of the season, and then once the obstacles have been cleared, a track established or the ‘tunnels’ dug it becomes easy for those who follow. Climbing routes that have been cleared, with an established track,simply in order to attain the summit, or keeping time in order to set records is in fact reducing the adventure of alpinism more to that of a sport climb, and strips the route of its full challenge making it more of a ‘playing field’ of a team sports athlete or like a barbell at an indoor gym where a jock tries to lift his personal best. As a young climber it is undeniable that I have been manipulated by the media and popular culture and that some of my own climbs have been subconsciously shaped through what the world perceives to be important in terms of sport. Through time spent in the mountains, away from the crowds, away from the stopwatch and the grades and all the lists of records I’ve been slowly able to pick apart what is important to me and discard things that are not. Of course the journey of learning never ends but I’ve come to believe that the natural world is the greatest teacher of all, and that listening in silence to the universe around you is perhaps the most productive ways of learning. Perhaps it is not much of a surprise, but so often people are afraid of their own thoughts, resorting to drowning them out with constant noise and distraction. Is it a fear of leaning who we actually are that causes this? Perhaps so many of us are afraid to confront our own personalities that we go on living in a world of falseness, filling the void of true contentment by being actors striving to be perceived by the world around us as something that we ‘supposed to be’ rather than living as who we are."1 point

-

I believe it failed because his climbing partner had to pick up the kids from Grandma's house at a certain time.1 point