-

Posts

1667 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Everything posted by Doug

-

Fuck, the asshole in the White House probably doesn't know what the word means!

-

I'll take tax and spend over borrow and spend any day of the week. Especially since the brilliant economists of GWB didn't see the rise in interest rates, which by the way are due in large part because of their moronic fiscal policies. I'm not opposed to lowering tax rates as long as 1) it is done equitibaly and 2) they don't jeopordize the future fiscal health of our nation.

-

It just goes to show that even those who believe they are of a higher moral fabric can become drunk on their power. Isn't it ironic that the group that has promised us more freedom is sytematically stripping it away? Lower taxes? Not neccesarily the answer to anything except "how do I get the vote of the average moron?" And oh yes, less government. Well, at least we agree on something. Sounds like principles and empty campaign promises are kind of synonymous. Speaking of campaigns, I see where dumbfuck, oops I mean dubya, is out trying to help raise funds for his fellow GOP'ers. With his current approval rating the best thing he may do to help is stay away!

-

Most sorority girls don't know what to think anyway.

-

And I thought I was the only one that noticed those traits in those who proudly declare themselves republicans. The two biggest republican losers on earth: Rush Limbaugh & Pat Robertson.

-

Holy shit! I'd be terrified that I wouldn't have any feeling in my hands!

-

Blake, you're a freakin' marketing genius! I might even offer up my private Stairmaster to work on the prototype! However, in order to work on the mental stamina part, I think recordings of your worst and whiniest partner should be included.

-

Hey, are those space pants? They must be 'cause your ass is outta this world!

-

Hmmm...did my post get deleted? if not, and I just screwed up, here goes again: Ephedra is on the market because it is not regulated by the FDA or any other body. It was banned temporarily due to pressure from a couple of high profile deaths that occurred in people that used it. There is also plenty of supporting anecdotal evidence suggesting links between ephedra use and cardiac and pulmonary abnormalities. The ban was lifted due to effort of lobbying groups (see G. Yngve's post) who worked to get it done.

-

Anyone remember the faux pas that the late, great Ronald Reagan made when he thought he was off-mike? The russian empire has been ruled illegal. Bombing begins within the hour. or something to that effect. He overcame it. Hoepfully at the end of this eight year nightmare the lingering effects of these idiots won't last too long. Hell, mabe the fucking debt they are running up will be close to paid off by the time my five year old is ready to retire!

-

It has been said that the difference between a religious person and a spiritual person is this: A religious person sits in church on Sundays and thinks about being outside. A spiritual person goes out on Sunday and thinks about god.

-

That takes what 35-40 minutes? Depends. One of the vehicles we carpooled in was a 64 VW Camper bus. We affectionately called it "The Bullet Train." In a headwind on the way home, it topped out at 45 mph. Coupled with the obligatory beer stop in Rosamond, that could be a 75 - 90 minute commute. Usually an hour covered it, especially if the MP's were being nice.

-

Renton to Everett (Van Pool) California - Lancaster to Edwards AFB (51 miles each way)

-

Eastern Washington, as in east of the cascades, or truly eastern? Omak. You wouldn't want to live in Ephrata. Too many rednecks, right Paul?

-

how many american lives were lost in that operation? there's no comparison to the two. clinton fired a warning shot across the bow, based on the data he was given. and ultimately, we found no wmd, did we? yeah, clinton was/is morally repugnant, but at least he possessed some level of intellect.

-

So Bush is in effect telling the dems "shut the fuck up. you assholes voted for the war, don't try to re-write history to make it look like my bad decision." I say fuck you Georgie . Based on the sales job you gave the congress & senate, they believed we were imminently threatened by Saddam. Now, we see that you fucking lied to them and all they are saying is "we were lied to." Doesn't sound like re-writing history to me. They saw your assholes cooked analysis of the intelligence (a word that will forever be linked to you in a dubious way) not the raw data.

-

Top that, Jobs!

-

"C'mon Jackie, Dallas will be fun"

-

Redneck: "Hey y'all, hold my beer and watch this!" Snowboarder: "Dude, hold the bong and watch this shit!"

-

If you have any kind of addiction issues (and yes there are food addictions) that's even better reason to stay away from a substance like ephedra.

-

I know someone who takes ephedra, and quite honestly I knew speed freaks years ago whose behavior paralleled this person's. Bunch of tweakers ready to jump out of their skin at anything. There's no doubt that weight is a huge factor in climbing, but if you've exhausted all other possible solutions (eat less, train harder)and you want a stimulant to supress your appetite, at least go see a Dr. and get a legitimate prescription. I think ephedra is nasty shit.

-

Isn't that the same percentage (give or take) that voted for Bush? Coincidence, I think not!

-

my condolences to the family.

-

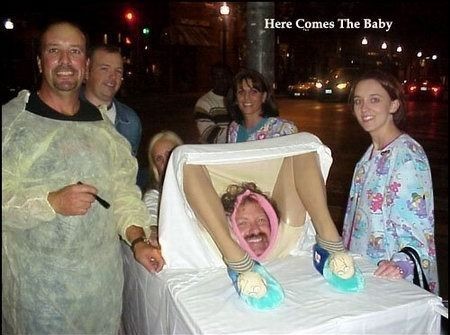

I thought I saw a thread on these, but I couldn't find it this morning. Here's my entry for best costume ever: