-

Posts

1254 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Everything posted by Kitergal

-

There is one God....and you are not it! Silly boys..trucks are for chicks!

-

exactly!! I'm thinking WTF!!

-

wholey crap girlz...you may be onto something!!

-

Anyone gonna be around Riley Beach? Let me know! I'm going the 3-13 of November! -M

-

####################### FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 21, 2004 Release #04-219 Firm's Hotline: (800) 997-HELI CPSC Consumer Hotline: (800) 638-2772 CPSC Media Contact: (301) 504-7908 CPSC, Wild Country Ltd. Announce Recall of Helium Carabiners WASHINGTON, D.C. - The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission announces the following recall in voluntary cooperation with the firm below. Consumers should stop using recalled products immediately unless otherwise instructed. Name of product: Wild Country-brand Helium carabiners used in rock climbing Units: About 1,000 Manufacturer: DMM Engineering, of Gwynedd, U.K. Supplier: Wild Country Ltd., of Tideswell, Derbyshire, U.K. Importer: Excalibur Distribution, of Sandy, Utah Hazard: The carabiner gate may come open under a heavy load, which will significantly reduce the strength of the carabiner. The carabiner could break if the climber falls, posing a risk of serious injury or death to the climber. Incidents/Injuries: None reported Description: These are Wild Country-brand carabiners sold under the following model names: Helium Dyneema, Helium DYN QD 5 X 13, Helium Clean Wire, and Oxygen-Helium. They are marked with batch codes AAA, AAB, AAC, AAD, AAE, and AAF. "Wild Country" and the model name are written on the carabiners. Sold at: Recreational sports stores nationwide from April 2004 through July 2004 for between $11 and $25. Manufactured in: United Kingdom Remedy: Consumer should call the firm for instructions on returning these carabiners. The firm will reimburse shipping expenses and send the consumer a replacement. Consumer Contact: Call Wild Country toll free at (800) 997- HELI between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. MT Monday through Friday or visit the firm's Web site at www.wildcountry.co.uk To view this press release online, use the following link: http://www.cpsc.gov/cpscpub/prerel/prhtml04/04219.html

-

where is K & K?? directions please!!

-

k. it's really official this time. I'm not going now. I'm heading up sharkfin and sahale instead. BUMMER...sorry I'm going to miss it. sounds like WAY MUCH FUN!! -M

-

hey guys sorry! his e-mail is DARRYL LLOYD longshadow@gorge.net -m

-

MORE!! and..no..I haven't even read through it all myself..yet!! High stakes proposals Meadows, Inc. looks for more real estate — on Mount Adams HOOD RIVER NEWS, September 25, 2004 By CHRISTIAN KNIGHT, News staff writer Its top chairlift would unload skiers at 11,100 feet, making it the highest ski area in North or South America. Its 2,500-units of housing, including condominiums, houses and a hotel, would slate it the first international destination ski resort in Washington or Oregon. Its casino, three 18-hole golf courses, interpretive center and village would qualify it as a year-round, eco-resort. What the Yakama Nation is trying to figure out right now, however, is whether all of this, the eight chairlifts, gondola, tram and spa, would decimate one of its most powerful spiritual symbols – Mount Adams, or Pah-to. This June, Mount Hood Meadows officials approached the Yakama Nation with a master plan to develop a mega international destination resort on the southeast side of Mount Adams. That area is the western-most boundary of the Yakama’s 1.4 million-acre reservation, which stretches from Mabton to Yakima. The National Forest Service manages the western slope. For skiers, the resort would offer the most vertical terrain in the country, 5,700 feet. And the drive from Hood River wouldn’t be too bad – 45 minutes along improved roads, says Mount Hood Meadows General Manager Dave Riley. “It’s a logical extension of where Hood River is going,” Riley said. “At the end of the day, however, it’s the Yakama Nation’s decision. What’s good for the members of the Yakama Indian Nation is what’s most important.” To facilitate the Yakama, Meadows has included in its master plan a Yakama Indian Nation Learning Institute, a facility that would house classrooms, interpretive centers and summer camps for tribal youth. “What we envision is a resort that reflects and interprets the culture of the Yakama Indian Nation,” Riley said. The resort would also offer the Yakama a significant boost to its economy, which currently relies heavily on timber, agriculture and a casino in Toppenish, Wash. But at what price? Ernie James Teeias is a Yakama Nation tribe member from White Swan, near Toppenish. Carpal Tunnel surgery has kept him out of work at Wapato for the last month, so he’s been helping his son and grandson sell salmon at the parking lot near Char Burger, beneath the Bridge of the Gods in Cascade Locks. He heard about the proposal about a month ago. It scares him. “That’s our wilderness up there,” he says. “It has a lot of religious meaning for a lot of people. I would be completely against it. Everybody (tribe members) I’ve talked to has been against it.” Unlike municipal city council meetings, in which elected councilors vote and ultimately decide on issues, the Yakama decide on its issues through a direct democracy: each tribal member has one vote and the majority wins. To open a meeting, however, at least 250 tribal members must be present. “I would go back,” Teeias says. “Just to vote. But I don’t think my vote would make any difference. Cause everybody I talked to would vote against it.” Teeias’ stance doesn’t necessarily represent that of the entire 10,000-member Yakama Nation. Soon after the General Council heard the proposal, it delegated a committee, which oversees Mount Adams affairs, to evaluate the proposal. “The Yakama Nation doesn’t just jump into anything,” said the chairman of the Yakama Nation, Jerry Meninick. “We study all the what-ifs. We have to be sure.” Before it can move on anything, Meninick said, the tribe has to explore the environmental, cultural, economic impacts, as well as the solution of a 49-year land battle between the federal government and the tribe. In 1855, a survey incorrectly omitted 21,000 acres from the Yakama’s reservation. Not until 1972 did President Richard Nixon return those 21,000 acres to the Yakama through an executive order. By then, however, Congress had passed the Wilderness Act of 1964, which had protected millions of acres of forest throughout the nation from development, including 10,000 of the most pristine acreage Nixon was returning to the Yakama. The Yakama accepted the returned land with a pledge, according to Yakima Tribal Council Resolution T-13-71: “(The Tribe)... will continue to recognize the dedication of that portion included in the Mt. Adams wilderness use ...” Simply put: Are the Yakama obligated to manage those 10,000 acres of previously classified wilderness, as wilderness? “In order for the tribe to even initiate those types of plans (development on Mount Adams) we have the responsibility of seeking approval (from federal and state governments),” Meninick said. “We face an almost insurmountable amount of red tape.” Mostly, however, tribal leaders are trying to figure out where a modern proposal such as this fits into a culture, which people recognize more by its tradition that its business practices. “That mountain represents a very significant spiritual side of us as a people,” Meninick said. “That right now is butting heads with the contemporary valuation of economics. The question that is directly facing the tribal council and our people, is at what cost of our traditional values do we approve such a venture?” Already, a conservation group is forming under the urgency of Darryl Lloyd a photographer and climber who has spent much of his professional and recreational life on Mount Adams. Lloyd formed “Friends of Pah-to” in the 1970s to discourage sloppy recreational use on Mount Adams. Now, with e-mails, maps and arrows on photos, he’s resurrecting the old coalition to prevent what he might call the sloppiest recreational use of all on Adams: development. “It’s an outrage,” he said. “An absolute outrage. But it’s a delicate thing because it’s the Yakama Nation’s. We might influence them in some way by massive public outcry ... This will be the mother of all wilderness battles.” Meadows’ Riley says he’s prepared for the same fight that has followed him through his efforts to develop Cooper Spur and Government Camp. “I’m expecting the usual opposition from the usual sources to any kind of resort development,” he said. “The greater point here: there’s a tribe of 10,000 people who are exploring opportunities to improve their prosperity.” ==================

-

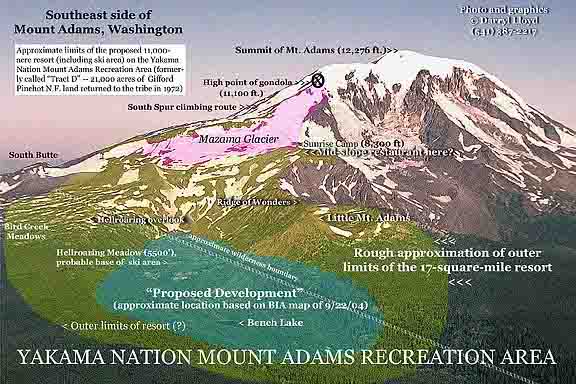

The following message and map-photo showing the proposed location of this resort on Mount Adams were prepared by Darryl Lloyd. Attached is a photo and graphics to show the approximate extent of the proposed resort. Feel free to forward. Please let Darryl know if you'd like a 6x9 high-res print, or digital file to reproduce. Yesterday's Oregonian had the article below about the proposal. Yakama tribe gets proposal for Mount Adams ski resort Mt. Hood Meadows outlines an 11,000-acre project that would include a casino, housing, golf courses and cultural museum Thursday, September 23, 2004 MARK LARABEE Mt. Hood Meadows Development Corp. is proposing a destination resort on tribal land on Mount Adams in rural south-central Washington that would have 10 ski lifts and three 18-hole golf courses. As presented to the Yakama Indian Nation, the 10,000-member tribe that owns the land, the resort would encompass 11,000 acres near Bird Creek Meadows. It's a popular area now used by campers, climbers, backcountry skiers and hikers. Meadows' proposal includes eight chairlifts, a gondola and a tram that would take skiers as high as 11,100 feet above sea level from 5,400 feet -- the biggest vertical rise for any ski area in North or South America. It also proposes three golf courses, a spa, a casino and 2,500 housing units -- a mix of hotel rooms, condominiums and single-family homes. There also would be ski lodge and golf clubhouse buildings, plus a small village with restaurants and shops. Meadows has struggled to build destination resorts at Government Camp and Cooper Spur on Mount Hood. Dave Riley, Meadows general manager, said the project also would include the Yakama Nation Institute of Learning, which is envisioned as an interpretive center for classes and a museum to highlight the tribe's history and culture. He said everything from the building design to food would incorporate Yakama culture. Although acknowledging opposition from environmental groups, Riley said Meadows will use cutting-edge building practices that focus on sustainability and environmental ethics. "It's clear that if this resort is developed, the Yakama Nation will insist that it will be the most environmentally sensitive development in the history of resorts," Riley said. "At the end of the day, they are going to do what they think is right for their resources and their people." At 12,276 feet, Mount Adams is the second-highest peak in Washington after 14,411-foot Mount Rainier. Its massive girth makes it the second-largest Cascade volcano in volume behind 14,162-foot Mount Shasta in California. But Adams is far from major towns, and a resort there would require significant road improvements to handle traffic, Riley said. Ownership dispute The mountain is not without controversy. For nearly five decades, the Yakama tribe battled with the U.S. government over its ownership. The tribe said boundary lines were incorrectly drawn after a surveying error. President Richard Nixon ended the dispute in 1972 when he signed over half the mountain to the tribe. Tribal leaders acknowledge that such an aggressive development would drastically change the character of the mountain they hold sacred. "Our understanding, even in a contemporary setting, is that if it was not for Mount Adams, the watershed would not be there to provide the nourishment for our timber, and all the food and medicine for our people," said Jerry Maninick, Yakama tribal chairman. "That's part of the commitment the mountain made to the Creator for all of eternity. Her task would be to take care of us and provide for us." Maninick said some tribal members think the resort proposal fits within that cultural belief. He agrees with Riley that the resort would be a financial boon for the economically struggling tribe. Today, tribal members rely on forest products, a small casino in Toppenish, a juice company, a land-holding company and farms for income. Benefits for Yakamas Riley said the proposal would be a partnership in which the tribe would own the land while Meadows would build and run the resort. Tribal members would get jobs and a share of the profits, he said. Maninick said the tribal council has formed a committee to look at whether such a development is feasible and in its best economic and cultural interest. Meadows has not yet released its proposal to the public. But similar proposals in the past have gone nowhere, and the tribe shut down a small ski resort on the land after it regained ownership. So far, Maninick said tribal members seem to be split over the idea. Eventually, all voting members will be asked to weigh in -- a vote Maninick expects to come by year's end. Maninick said the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs also would review the proposal and take testimony. The resort proposal is drawing critics outside the tribe. "We will fight the Meadows proposal with everything that we have," said Brent C. Foster, a Hood River attorney with the Gifford-Pinchot Task Force, an environmental group focused on reducing clear-cutting and road density, and preserving wildlife habitat. "This is incredibly important habitat, and the idea of putting thousands of luxury vacation units up there is an outrage, to put it mildly." Opposition on Hood Meadows' proposal to build a similar resort on Mount Hood's Cooper Spur continues to have fierce opposition from environmental groups and some Hood River Valley residents who rely on the watershed for drinking and irrigation. The ski company and opponents are in mediation over the plan. Riley reluctantly acknowledges the political fight ahead. He said many people will try to tell the Yakama Nation what to do. "Central Oregon has 25 golf courses," Riley said. "Some people think that's a great thing in terms of quality of life, and others would say Central Oregon would be better off it if didn't have any. This is the Yakama Nation's decision, not the Sierra Club's." Maninick said although he's undecided, he's intrigued by the long-term economic prosperity the resort promises. Even so, he said, the tribe might not be ready to take such a drastic step. "One of the areas our people have difficulty in is economics," he said. "It's almost always difficult for us to adjust ourselves to the contemporary setting. It's a high-risk area for our people, and they're a little gun-shy." Mark Larabee: 503-294-7664; marklarabee@news.oregonian.com * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * The first report of it appeared in the Yakima Herald-Republic on 9/13. Destination or Desecration? By PHILIP FEROLITO YAKIMA HERALD-REPUBLIC Despite having the potential of bringing in millions of dollars, putting a resort offering one of the highest ski lifts in the country on Mount Adams would be a desecration to Mother Earth, some tribal members say. Recently, Mount Hood Meadows Development Corp., which owns Mount Hood Ski Resort in northern Oregon, approached the Yakama Nation with a proposal to construct a massive four-season resort, which would put 11 ski lifts reaching the 11,100-foot level on the south side of the mountain. It would also include three 18-hole golf courses, a mid-sloped restaurant, casino, night club, and 2,500 lodging units. The corporation is calling the project an "eco-resort," meaning it would incorporate the Yakama heritage in theme and design and offer a summer camp for tribal youth with year-round educational courses on Yakama culture, said Dave Riley, vice president of Mount Hood Meadows. "Because of our local experience, we understand and appreciate northwest tribal interests and rights, and the importance of the Treaty of 1855," Riley added. Developers pitch such ski resort and other outdoor recreation projects to the nation every few years, but the tribe isn't rushing into anything, said Yakama Nation tribal Secretary Davis Washines, who goes by his traditional name Yallowash. The full tribal council has yet to hear the proposal, and it would have to be approved at General Council, where voting tribal members decide on major decisions and elect the 14-member tribal council, which oversees daily operations of the Yakama Nation. But the idea of putting any kind of development on the mountain located in the closed section of the Yakama reservation has some tribal members up in arms, said Regina Jerry, assistant minister of the White Swan Shaker Church. "I feel that that would be a terrible violation of our people if they open that up," said Jerry. "(Tribal leaders) were sworn to an oath to protect the things that are sacred to our people." The closed area consists of more than 600,000 acres of wildlife and natural habitat stretching from Ahtanum Ridge to below Satus Pass, and reaching to Mount Adams. There, only enrolled Yakama tribal members are allowed to practice sacred food gatherings, such as berry picking, root digging, and hunting and fishing. Outsiders need tribal permission to enter and must be accompanied by a tribal member. Guarded by four main gates, the tribe closed the reservation during the 1950s to protect wildlife and the natural habitat. The only structures there are a fire and ranger station and Camp Chaparral, which consists of a few living dorms and a dining hall. "That's the last place we can go and camp and try to get back to our traditional ways," Jerry said. The tribe engaged in a 49-year boundary dispute with the federal government before President Richard Nixon in 1972 returned half of Mount Adams to the Yakama Nation. Today, remains of a former ski resort are still present on the mountain's south side, where Mount Hood Meadows wants to build. The tribe kicked the resort off after reclaiming the sacred mountain, said tribal council chairman Jerry Meninick. The more than 12,000-foot-tall volcano is much more than a mountain to the Yakama, he says. "It tells us of the many different disciplines ... reminders of our existence," he said. Yakama legends describe the mountain as a living being that's responsible for taking care of the people below, said Johnson Meninick, cultural resources manager for the Yakama Nation. "You can't get a queen and climb all over her and dance on her," he added. The mountain, like everything else in the arms of Mother Earth, is part of an unwritten law patterned after the natural resources that the tribe has lived on for thousands of years, Johnson Meninick said. "The resources don't belong to us, we belong to the resources," he added. "Resources are the giver of life." However, the earning potential of such a resort — which tribal members would receive a share in its profits — has some tribal officials weighing cash against culture, Jerry Meninick said. "We're talking a multimillion-dollar industry," he said. "It's something that needs to be taken very seriously." But the resort would be a hard sell to the tribal membership, Meninick admits. "It would be very difficult to present this to General Council and have them pass this resort," he said. "If the tribe didn't have the values on its religious beliefs, according to the feasibility (of the proposal), it probably would have been done by now." Though creating more income for the tribe is important, tribal officials don't want to give the impression they're moving ahead with the proposal or ignoring the cultural aspects of Mount Adams, Yallowash said. "Even myself, I get up in the morning and that mountain is the first thing I see, and I have these same concerns," he said. Also, the legalities of allowing non-Indians into the closed section and getting building permits approved would require legal research since federal law supports the closure, Jerry Meninick said. "Do we go back to U.S. Supreme Court and get a clarification?" Johnson Meninick asked hypothetically. Questioning who would actually own the resort, Johnson Meninick noted that tremors in the area have been increasing the past five years. "Who's going to be responsible for the lives that would be lost in an avalanche?" he asked. "We don't have anyone stepping forward to say, 'This is my project.'" * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Let me clear up some inacuracies in Philip Ferolito's initial news story. There was never a "former ski resort" on the south side, just a little hill near Wickey Creek that had a rope tow and the 3-sided "Wickey Creek Shelter." It was put in by the USFS around 1939 and taken out during WWII. The shelter is still there, next to FS 8240 Road at 3,600 ft., and is well inside the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. I know of nothing that was halted or removed from the 21,000-acre "Tract D" area after it was returned to the Yakama Nation in 1972 You may be interested to know of the Tribe's continuous wilderness management on Mt Adams since 1972. The policy came from "Yakima Tribal Council Resolution T-13-71" (passed by unanimous vote on September 8, 1970), which addressed the 21,000-acre area prior to Nixon's Executive Order. It's quite lengthy, but one sentence says: "(The Tribe)... will continue to recognize the dedication of that portion included in the Mt. Adams wilderness use..." The "portion" referred to is about 10,000 acres of Mount Adams Wilderness that would be placed in trust for the Yakama Tribe. President Nixon, in his Executive Order signed on May, 20, 1972, said: "I am equally pleased to note that the Yakima Tribe itself has pledged by Tribal Resolution to 'maintain existing recreation facilities for public use' and to 'recognize the dedication of that portion included in the wilderness use.' " ------ End of Forwarded Message

-

Hey..change in plans..I'll be heading up Friday also! Anyone carpooling from the Issaquah/Seattle area??

-

OMG...it is a Mountaineers outing......

-

Low key? bars? climbs? looking for FUN! Tonight (friday 9/10- meeting peeps at the roanoke) saturday-Anyone want to go to Vantage??

-

umm wait...is this a Mountaineers outing?? what site am I on??

-

Snowbyrd!! Simmona! YEAH!! Cooo!! I'll definately be there then....well..maybe! Yeah..see...I have this schedule deal...it's kind of a pain in the ass....but I will try to make it! you guys heading over friday or sat?? M

-

cooo...I'll probably be there then! I have a huge fear of commitments, so I can't commit to being there but I can tell ya that I'll probably show up with my pup in tow!! Marie ummm..how will I recognize ya'all? Are any of the kick ass Prana girlz going?? If not...I'm not gonna know ANYONE there...and..umm...I'll be scared!!

-

Are dogs allowed at Bridge Creek? If I remember correctly, the whole area is NOT dog friendly....true or false?? Thanks guys Marie

-

k. help me out...what the heck is a 4th annual rope up? Can noobies go? I can't make it friday night (hosting a murder mystery party at my place...anyone wanna come? I need more actors!!) But I can definately head that way come Saturday morning...if of course...noobies are welcome! Please advise! Thanks Marie

-

K. I'm there next week. I'm ditching all other commitments and I AM THERE!! FINALLY! Wonder if I remember how to put on my harness!! -M

-

k. wait...get there earlier?? Hmmmm I can't promise that?! August is a HELLACIOUS MONTH at the ol' job front! but..If I can show up my usual late time..then I'm still game!! -M

-

I'm in! Always willing to learn, as long as we can drink afterwards!! btw..it's been confirmed, ditching the cute sailor for you girls...YOU ARE PULLING RANK HERE!! -M

-

Ladies Wednesday Climb 7/28 Goes to the "Far Side"

Kitergal replied to icegirl's topic in Events Forum

all right..all right!! Just thinking of the sailboat races I play in every tuesday night..once a month we have theme night and it gets kinda crazy!! But your right...lets just climb!! -M -

Ladies Wednesday Climb 7/28 Goes to the "Far Side"

Kitergal replied to icegirl's topic in Events Forum

We should start theme nights!! were we all dress up to climb! 70's, 80's, PJ's, Formals, Toga, Hawaiian! I mean..we'd still have to be able to put a harness on over it..but think of the looks we'd get from the others...not to mention the after hours at the bars!! -M wow..am I sounding like a CL again?? -

Ladies Wednesday Climb 7/28 Goes to the "Far Side"

Kitergal replied to icegirl's topic in Events Forum

k girls..heres the pics from my camera (and a couple that I stole from Breezy D's gallery..yes I finally found it!). NOO you don't have to actually buy them! just shoot me an e-mail (gattim@hotmail.com) as to the ones you want me to send you..and I'll send them individually! Make sure to send me the address you want them sent too! (copy and paste the link below into your browser to view the album) http://www.ofoto.com/I.jsp?c=12bxreh3.84rdpczj&x=0&y=i09amz questions? shoot them my way! -M -

Ladies Wednesday Climb 7/28 Goes to the "Far Side"

Kitergal replied to icegirl's topic in Events Forum

Can we re-name this to the double D's?? HA HA HA HA !!! -M