Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 09/01/21 in all areas

-

Trip: Les Drus, Chamonix - American Direct/Classic north face finish Trip Date: 08/14/2021 Trip Report: The nearest big peaks to me are those above Chamonix (I am aware of how lucky this makes me), and from the valley floor, none call quite so strongly as the Drus. When I first went to Chamonix in November 2019 for some skiing, I was actually in a pretty bad mental state, tired and depressed. The initial views of Mont Blanc and the Chamonix Aiguilles kind of failed to light my internal fire, but once we reached La Praz, the almost overwhelming view of the Drus rocketing above their surroundings snapped me out of my stupor (I'm doing better these days). The seed was planted. This summer in northwestern Europe has been pretty much the opposite of the summer in the northwestern US, unusually cool and wet. I'm certainly not complaining, but it's made climbing a lot harder to do and I have done a lot fewer pitches of climbing this summer than last, which has not been good for my fitness. At the same time, this is the last summer of my work contract in Geneva, and the knowledge that I would have to make the absolute best of any weather windows that I could get only served to swell my ambitions, admittedly a bit of a dangerous combination. I'd engaged in semi-serious talk with an American I met last summer via Mountain Project named Jared about getting after the Drus via the proudest line we could think of, the American Direct. By late last July, the above factors put me in the psychological position where I was willing to put all of my chips down and try to go as big as possible on the Dru if I could get the point, and I let Jared know. The start of August sucked in the mountains, and I had a few climbing trips in a row get canceled by high winds, snow and avalanche danger, or more high winds. Suddenly, things cleared around August 10, with the promise of a long period of high pressure that might melt some of the snow and ice covering basically all of the rock above 10,500' or so. The long awaited weather window had arrived. I arrived at the Montenvers train station and hotel early afternoon on Friday, August 14. It was super hot, so once Jared met me we decided to wait until a bit before 5PM to start the supposedly roughly 3 hour approach hike to the base of the wall. This left plenty of time to stare at the wall and get intimidated. The route, as planned, starts from basically the lowest part of the face and heads up trending right in the orange-gray rock, until encountering the gigantic light gray rock scar left behind by the collapse of the Bonatti Pillar in huge landslides in 2005 and 2011. Here we would diverge from the original Hemmings and Robbins route via an aid pitch to scoot left onto the shady north face, and then follow the classic 1935 Allain-Leininger north face route to the top. From the base of the rock to the summit is about 3300' of wall. The near-catastrophic retreat of the Mer de Glace has exposed hundreds of feet of blank slabs that were buried under ice just 200 years ago. Luckily, guides have installed ladders to overcome this obstacle. After crossing the Mer de Glace, a series of exposed 4th class scrambles protected by fixed ropes (no ladders on the far side, not enough traffic heading to the Petit Dru to justify them, I suppose, which makes sense) lead to a barely-there climbers trail that traverses a lot of nice meadows. It's kind of like the North Cascades, but with much bigger mountains in the background. Approaching the objective, can you spot the trail? Actually it wasn't too hard to follow, there were cairns and occasional ribbons in trees. Eventually the trail kind of petered out into the sort of loose moraine that we all know and hate, and at the point I made two key fuck ups. First, in the last vegetated area, we stopped to refill our water. This required me to empty my pack in thigh-deep vegetation in order to access my Camelbak. More on that later. Second, Jared and I kind of naturally drifted apart as we picked our was through the shitty moraine mixed with pools of water. The complexity of the terrain meant that we lost visual track of each other, but we weren't concerned because we were pretty experienced with this kind of slog. Eventually I picked up a faint trail and followed it up a long, loose moraine crest to a good rest spot, and waited for Jared, who had been behind me, to catch up. When he failed to appear or answer my calls, a bunch of highly unrealistic but very worrisome scenarios started to creep into my brain, and I dropped my pack and hiked hundreds of feet back down the loose crap. Eventually, I managed phone contact with him and learned that he had opted to contour around the moraine and then climb up the other side of it from where I was. When I described my location, it turned out that my little hike down looking for him had managed to give him a solid 30-40 minute lead on me. Oops. View from the top of the moraine. Finally, we reached the bivouac sites atop the Rognon des Drus, shortly after sunset and nearly an hour later than we'd hoped for. Exhausted and hungry, we started to prepare for dinner. It was then that I discovered, to my horror, that the gas canister I'd been carrying was gone. I can only assume it was lost in the vegetation below the moraines from where I'd refilled my water. This was clearly a pretty bad mistake, and made me really upset and embarrassed. After some thought, we still had running water, and cold food is still edible, so no plans were changed. Dinner was cold, crunchy pasta in a freeze-dried bag meant for boiling water but with snowmelt instead. Oops. Also, I realized that in the chaos of our separation and my abandoning and hiking back to my pack while trying to look for Jared, I'd lost my expensive glacier goggles. Oops. We awoke by 4AM under an astoundingly starry sky and got moving under what I hoped was a fresh start from the previous day's amateurishness on my part. We had vague ambitions of reaching the summit bivouacs but mostly wanted to get high up the wall before the Niche des Drus started dropping big rocks on the start of the route, which is probably the most dangerous part of the route for rockfall. The snow moat at the base of the wall was thankfully minimal, but the start of the route itself was a bit harrowing. It consisted of 5.4ish slabs and grooves with a literal waterfall running down it, enough that water would run down my sleeves as I tried to climb through it. It was also pretty much entirely unprotected save for a single shallow 0.2 X4 placement I found behind a flake, and we were moving together, so a slip by either or us would have been a catastrophe. After this exceptionally rude awakening, we reached a dry ledge with a bolted anchor, changed into rock shoes, and got the first dawn light to see where we were going. We simul-climbed the next 6 pitches of 5.7 to 5.9 in 2 blocks, which felt honestly great and we kept moving along at a good pace. I did notice I was sipping on my hydration hose worrisomely fast, probably a result of my lack of acclimatization (the bottom of the route is at 9000'), but this didn't feel like an enormous problem yet, as we were climbing in the early morning on a west face in the shade. By 8AM we reached the golden rock of the headwall and the climbing quality went from really good to spectacular. This is the first money pitch (pitch 11), the 40m dihedral, which is probably about 5.10d. It is as fun as it looks. Our strategy was to climb with our packs on unless the climbing was hard enough to make it really impractical. For us, that meant the packs were pretty much always on, but we hauled the 40m dihedral, which Jared found to be fairly miserable experience between the weight of the packs and how thin the 6mm tag line was that we used for the task. After that, we stopped hauling. I started slowing down between the increased difficulty of the climbing and mounting fatigue. We largely stopped simul-climbing, and I was also beginning to become acutely aware of my dwindling water supplies, as there was no snow or water available anywhere on the wall, it was just too steep to hold moisture. I also wasn't eating enough because of how dry my mouth was, which further cut into my energy levels. Jared following pitch 14, another nice 5.10 corner. We kept moving upwards with very few breaks (Jared had to coax me to adhere to this) until we reached the very nice jammed block bivy site atop pitch 20 at about 1:30PM, at about the same time that the sun did. As things tend to do when the sun comes out, it got a lot warmer really fast and I finished off my water. I was very dehydrated, so I wasn't able to get much food down, so my energy levels were a bit shit. Grateful to be climbing with a stronger partner, I told Jared he'd have to lead the crux pitches to come, which he was fine with. This is the crux of the route and it's crowning jewel, the so-called 90 meter dihedral. It's a long, smooth-sided finger crack dihedral in very smooth and top-quality granite. After an approach pitch up the start of 5.9+ or so, it gets broken into two long and pumpy pitches of 5.11b or so. Jared led the first pitch with no pack on and then hauled his pack up in a fine effort. To save him some suffering, I kept my pack on as the follower and commenced one of the hardest fights I've done on rock in a long time. A full pitch of fingerlocks, smearing, painful toe jams, and palm presses got me to just a few moves below the anchor when I needed to take. The 2nd pitch, if anything, is even cooler, but probably harder. Hauling again was miserable, so Jared tried to lead with his pack on, which proved very difficult-looking when the climbing turned into 5.11 laybacking off of a finger crack with smears for feet. After quite a few hangs and some pulling on gear, he made the anchor. At this point, I was completely gassed and I basically aided the pitch, standing in slings, pulling on whatever gear I could, the works. I regret this, but it's hard for me to feel too bad about being unable to climb 5.11 granite 23 pitches up with a big overnight pack on. After the 90m dihedral, the original route heads right towards the rockfall zone via a pendulum. Instead, we opted for the "German Rescue Traverse," which follows a bolt ladder to the left over the void towards the junction with the classic north face. Jared on the aid pitch. This one is just as much fun for the follower, and I was sloooow on it. The fixed rope is apparently pretty new, as are a couple of the bolts, since some of the horrifying old bolts that used to comprise the traverse appear to have broken. Reaching the comfortable bivy spot at the end of the traverse was a relief, and we decided to stay there for the night. Luckily there was snow and a bit of dripping water, though without gas it was definitely still a deprived situation. I ended up sleeping with a camelback full of snow in my sleeping bag with me to melt it for the next day, though not before realizing I'd forgotten my wag bag and shamefully pooped on the ledge and then flung it off the cliff into the abyss as far away from the standard north face route as I could manage (I swear that's the first time I've ever done that). Oops. The sunset from the bivy site was divine. My "cozy" little spot. I definitely woke up and checked to make sure I wasn't sliding towards the edge a couple of times in the night. We awoke at 5AM in order to get moving again, I was still pretty tired from the previous day but had grim determination to see it through. Ahhh. Alpine starts. It was extremely cool to get to climb on the historic 1935 route up the north face of the Drus. The face was considerably less chossy than its reputation and appearance from afar had led me to believe, and the rock was generally good. We started by simuling a couple of pitches, then I led the Fissure Martinetti bypass to the original crux, figuring getting to the top by the path of least resistance was challenge enough. We immediately canceled out this energy-saving measure, however, by getting a bit off route, with Jared leading a thin finger crack in a slab that felt like 5.10c or so, but it was hard to tell because it was a bit wet and I stood on a piton to get past the snowy start. Once back on route, we quickly pushed to the upper face via a couple of blocks of simul climbing, with ever expanding views. As we got higher, the rock got wetter and the ledges had more loose rock and snow on them. Near the top of the face, there was a bit of easy chimneying kept interesting by ice in the back and water running down one side. Classic north face stuff, I presume. Never hard enough to be a big problem though. North face ambiance. Yes, I was kicking steps up the snow in my TC Pros towards the end. Eventually we found the fabled hole through the mountain towards the south face, and opted to pass through it to finish up, mostly because climbing in the sun on drier rock again sounded nice. A couple rope lengths and a couple of route finding errors later, and I found myself with no higher to go. The summit of the Petit Dru! I had expected catharsis, but felt mostly mild relief that I could stop going up (at least for a moment). It's hard to relax much on a summit like that with such a long descent ahead. Nonetheless, I scrambled down to pay my respects to the summit Madonna. Can't imagine dragging that thing all the way up there. The next task was to traverse over to the Grand Dru with it's rappel descent. This consisted of a short scramble down followed by a few short, wandery bits of crack climbing up to 5.9 that culminated in a wet squeeze chimney. Entering the chimney, I very briefly considered taking my pack off and committing to the free grovel, but quickly decided that the knotted rope in the back looked more appealing, so an aid pitch it was. Finally, we found ourselves on the summit snowfield of the Grand Dru. Jared on the highest point of the Drus. Summit panorama. Not a bad view at all. Amazing spires all around. Not much can be said about the rappel descents on the south face of the Grand Dru other than that they were long, wet, and tiresome. The rope got hopelessly stuck on the pull after the very first 45m rappel, forcing Jared to lead 2 pitches to get it out of the flake that had eaten it, which definitely soured the mood. Mercifully, there were no more incidents for the next 10 rappels down to the Charpoua Glacier. The glacier was in decent shape, but the snow was incredibly soft and repeated post holing got my socks quite wet. Once we neared its bottom though, we were confronted with a small ice cliff of about 40 degrees that we had to front point down. I'd compare it to a short version of the first pitch of the Kautz. The mountains refused to just let us go easily. Steep wet snow. The small ice cliff we had to downclimb. The two summits of the Drus on the left from once we were finally below the glacier. The Aiguille Verte is on the right. Finally we were able to unrope and a short hike brought us to the Charpoua Hut, where we were able to get a nice dinner. It was clear that the weather was taking a turn for the worse and also that our plans to hike out that day had been thwarted by general slowness. The decision was made to get as low as possible before finding a place to bivy. Sunset from the Charpoua Hut. The next few hours were quite unpleasant. The trail followed easily enough until it got completely dark, and it became clear that my Swiss map app that I had on my phone did not have the right trail positions marked for these very French mountains (go figure). We wasted lots of time, energy, and patience with each other repeatedly losing and refinding the trail, including a big detour following a trail that petered out. It later turned out that the trail we tried to go down had been abandoned because it was exposed to serac fall from the Charpoua Glacier and in the dark we didn't really realize the danger. Oops. Finally, however, we got on the correct trail and things were going pretty well, except for the increasingly frequent but still silent flashes of lightning coming from the west. At about 11:30PM, we figured we were getting pretty close to where the trail descended steeply to the Mer de Glace and not wanting do deal with that, we looked for a place to sleep. Jared quickly found a very inviting-seeming cave with a nice flat floor formed by a large boulder. I crawled in to the back (the ceiling was pretty low) and Jared set up his bivy closer to the entrance. All seemed well. A mere hour later we were brought to attention by several very loud and very close thunderclaps, followed by a quick start to what sounded like an impressive downpour. In the back of the cave, I felt a bit of mist in the air, but Jared gave a cry of alarm. Close to the mouth of the cave, the wind was blowing rain on him, and water running across the roof was dripping on him and to a lesser extent on me. I moved to shove myself farther back to give him room to seek more shelter. Jared, however, sounded increasingly frantic, followed by cries of "there's a hole, there's a hole!" Not understanding, I turned on my light, only to see to my horror that my inflatable groundpad was surrounded by a flood of water between 1 and 2 inches deep, making it basically a life raft in our flooding bivy cave. I grabbed a rock and started digging a trench to drain some of the water out and prevent myself from being overtopped. Jared's situation was much worse. When scooting his ground pad towards me, he had popped it on something underneath him (the "hole"), causing it to rapidly deflate and drop both him and his down sleeping bag into a pool of freezing cold water. Luckily, the rain slowed and stopped as quickly as it began, and we managed to spend the rest of the night partially sharing my sleeping mat (though I must confess I took more than an even share) and huddling for warmth. The water drained away once it was not being replenished. Once their was light at about 5:30, we packed up our things, I silently thanked the weather gods that it wasn't raining, and got ready to move out. I'd been in the back of the cave between Jared and the entrance, so I remarked "at least that little breeze was nice," thankful for the ventilation. Clearly irritated, Jared snapped back that the breeze had kept him up all night shivering, and I remorsefully realized he'd had a much rougher night than I had. Despite that, he again put me to shame by setting a strong hiking pace out that I struggled to match, which is worthy of all respect. The cave as seen the morning after. We slept down and to the right in the slot. The south face of the Drus from the morning wet hike out. There were lots of ladders, both in the morning and all over the trail the previous night while we hiked in the dark. Morning on the Mer de Glace. Almost at the end of our hike out, the clouds parted one last time to give us a final view of the Dru, a source of a great adventure I'll remember for a long time. Writing this TR 5 days after that morning hike out, I can safely say that I'm still pretty tired and sore, and some of my toes are still a bit numb from all the jamming, but despite the low points and many small screw ups, it felt like a good experience worth doing. As of June 2013, the Old Chute route on Mount Hood was probably the most intense alpine climb I'd ever done. It's been wild to progress to a climb like this and I'm definitely interested to find out what the future holds, but I'm pretty sure at this point the remainder of my summer will be dominated by low altitudes and beers in the sun more than north faces and cold bivouacs. Once that bad alpinist memory kicks in though, well, I guess we'll see. Gear Notes: All the alpine stuff Approach Notes: straightforward by alpine standards1 point

-

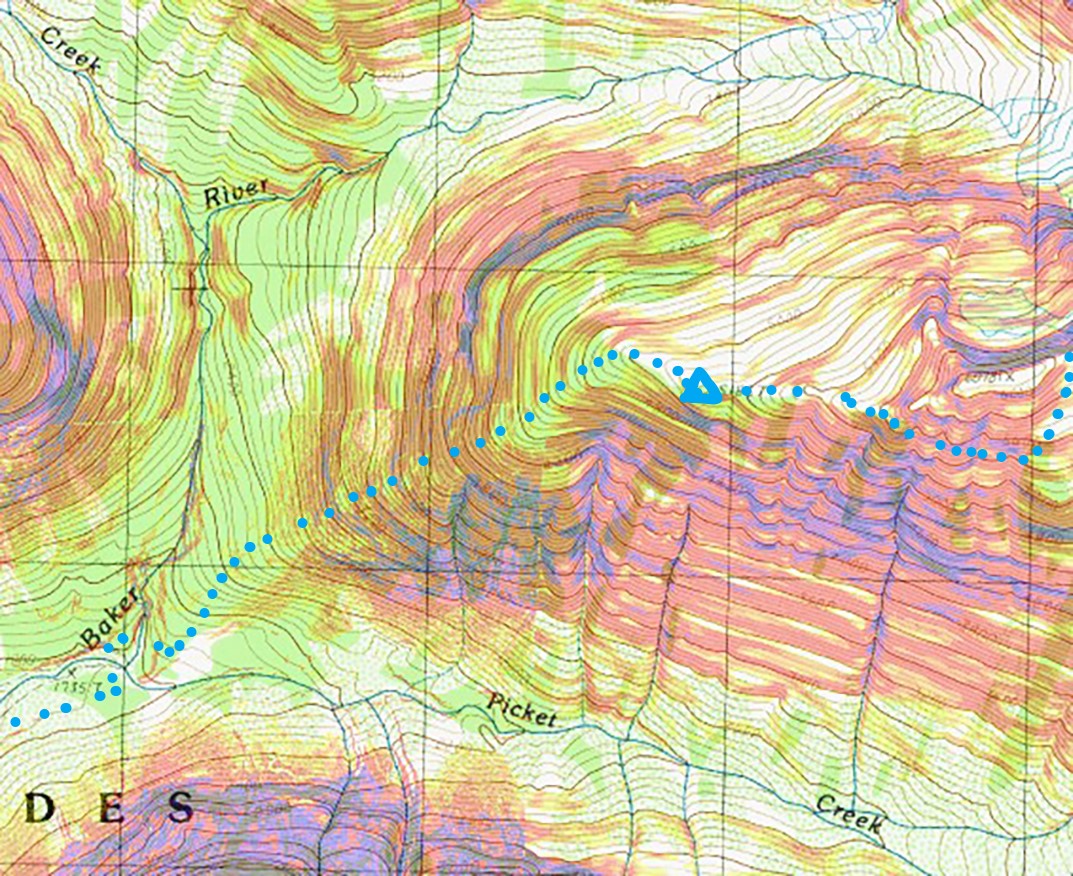

Trip: Northern Pickets - Mt. Challenger Middle Peak & FA of SW Ridge of Challenger 5 (Peak 7,696) Trip Date: 08/18/2021 Trip Report: Northern Pickets, image pulled from publicly accessible Google Book Preview of Cascade Alpine Guide, Vol. 3. The SW Ridge of Peak 7,696 is the righthand skyline. Fair use intended. TL;DR: Climbing partners Joe Manning (manninjo) and Joseph Montange ventured up the wild and rugged Baker River valley in mid-August 2021, seeking a shortcut into the Northern Pickets. After several days of travel, we climbed a very fun, new, five pitch, 750', 5.7 route on the Mount Challenger massif, the Southwest Ridge of Peak 7,696 (aka Challenger 5). Baker River Mandatory wading on day 1 starts several miles upriver Time to go to the beach! It’ll be fun: miles of sandbars and loads of deep blue swimming holes. Wading up the river in tennies. Getting to curl our toes in the sand. Sounds promising as a way to approach the remote and reasonably inaccessible Picket Range. Relaxing, beachy-type vacations are not my norm, so the Baker River seemed like the best of both worlds. Get the summertime water fix AND have an adventure scoping out the “direct” route into the Northern Pickets. The approach, documented in the 1968 Tabor and Crowder guide, has no record of folks actually going all the way in that way in the last 50 years. I’m sure some folks have, only to be swallowed by brush and never seen again. Mike Layton wrote in 2006 that John Roper “thoroughly sandbagged” him and Wayne Wallace on their approach to Spectre Peak by suggesting the Baker River. Following “six hours to travel a mile and a half along the Baker River we bailed. Ahead were three more miles of rain, brush, and swift water followed by a 5000-ft climb to the ridge… after our eight-hour false start, we dragged our soggy asses and 25-lb packs to the Hannegan Pass parking lot to restart the trip.” Pioneer Ridge (center-right) and the confluence of Bald Eagle Creek and Baker River For our part, we wanted to push beyond the Pioneer Ridge version of the Baker River approach and continue up the river, to the confluence of Picket and Mineral Creeks. From here, a spur ascending all the way to the Mt. Challenger massif would provide an escalator into the alpine. In fact, after all the beach time, we’d probably need to burn off some of those beach-induced calories. In all seriousness, there’s really no easy way into the western side of Northern Pickets. For a fit and competent party, stocked with full climbing kit and several days of food, Easy Ridge, Whatcom Pass and Peak, Eiley Wiley, even carrying over Fury all take at least two days. Sometimes fast and light parties get to Perfect Pass in a day for a two-night blitz of Mt. Challenger. But if you want to do something on the west side of Spectre, Phantom, Ghost, Crooked Thumb, anything on the south side of Challenger, it's two days just to get there (and two more to hike out). It was with this knowledge that we set off up the Baker River, hoping to find the equivalent of the Northwest Passage into the Northern Pickets. While we may not have found quite that, we did get to spend several days in one of the most rugged, wild, untrammeled and primeval wilderness areas this side of Alaska. The fact that access started less than a 90-minute drive from home was remarkable. The sheer quantity and apparent quality of the granite cliffs spilling off the sides of Pioneer and Mineral Ridges is mind boggling. It’s a beautiful looking mix of Index town walls, Squamish, Darrington, Yosemite, name any notable granite bigwall area. Were it not for a lack of trails and fixed anchor ban in the park, this zone would be a serious destination. As it exists today, it's worth admiring the incredible views every step of the way in. Just don’t forget to watch your step along the way. For folks who find off-trail travel “not so bad,” the stats are compelling. It's less than half the distance of any other way into the range, and less than half the elevation gain. There is no penalizing elevation loss. The approach lacks the objective hazards (e.g. icefall traversing around Whatcom Peak) and subjective hazards (e.g. exposed, loose scrambling over Whatcom or across the Imperfect Impasse) one would find coming in from other directions. The Baker River is a late season approach - the river needs to be low enough to regularly ford and wade. Most of the river walking we did was shin to knee deep. A pair of low top mesh approach shoes worked perfectly to hike in and out of the river. We got waist deep in the river once or twice, though that may have been avoidable. Make sure you line your pack with a garbage bag or other waterproofing. Sections of mandatory bushwhacking punctuate the river walking There is unavoidable brush, including some that registers as “BW5” on the Cascade Brush and Bushwhack scale. As with most off-trail approaches, the bushwhacking was far worse going in than coming out. Only a handful of times did patience grow thin and tempers flare due to frustrating travel conditions. Another dead end in the brush led Joseph to remark that “it wouldn’t be an adventure if there were no doubts.” At this point, with the hour growing late on the first day, we were having some serious doubts about the viability of the approach. After a breather and channeling the power of positive thinking, we made it through the worst of the brush and found ourselves a mossy camp in open forest next to a brook and several large boulders. With full packs loaded for climbing out of a base camp, it took about the same amount of time to go in this way compared to past experience with the more-frequently documented approaches. The crux of the approach, encountered on day two for us, was the wooded spur above the confluence of Mineral Creek/Baker River and Picket Creek. The wooded spur with approximate line and color showing slope angle It starts out innocuously enough. Low angle, brush-free walking past ancient cedars the size of skyscrapers, some well over 15 feet in diameter, soon gives way to steeper and steeper hillside. In what could be the toughest 2,000 feet of elevation gain anywhere, you’ll fight insanely thick brush, mostly saplings and huckleberries, all at a gradient of over 30 degrees, while dodging cliffs including a significant band at about 4,000 feet elevation. Helmets and dirt-ponning may feel necessary to descend safely. Steep huckleberry Typical brush thickness on the wooded spur Several cliff bands are hidden in the brush of the wooded spur Perhaps the effort overall is greater going off trail, though that is going to vary individual to individual. Climbers with their brushmaster degrees, good route finding skills and smaller, lighter packs could conceivably make it to the Challenger 4/5 col or Phantom alp slope camp (or pretty close) in a single big day via Baker River. We broke out of treeline on the afternoon of our second day, hiking into a thickening misty fog. Wonderful camping exists there on grass patches among the heather fields next to perfect 250 gallon tarns. Bring a water filter for the tarn water. Camping on a natural grass tent pad next to water around 4,900 ft Our third day, we woke up to driving rain - not the forecast we hiked in with. It broke into a light drizzle by midmorning and up the alp slope ridge we went, reconning for a higher camp. By midday, an updated forecast gave us a limited window to climb the next day only, August 18th. Chance of showers returned the afternoon of the following day, August 19th. Being well provisioned for several days of rock climbing, the change in weather was disappointing but we’d have to make due. Resigned to the revised forecast; Mineral Mt. in background As I’ve learned in the Pickets, 20 or 30% chance of showers is pretty much 100% chance of rain and low-to-no visibility. We ended up moving camp on day three just a half mile further up the ridge, to a larger patch of grass with an even deeper little tarn and mystifying views of Whatcom Peak, Mineral, Shuksan, Baker/Kulshan and numerous other mountains. We elected to leave base camp there on the ridge around 5,200 ft and go light above. Camp 2 on the ridge, Whatcom Peak in the mist and Perfect Pass at center right We had big (for us) ambitions for our week, yet somehow even the best-laid plans seemed to get waylaid by weather and slowed down by river crossings, vine maple, cliffs, huckleberry, and route finding. Southwest Ridge of Challenger 5 (Peak 7,696), 5.7, 5 Pitches, 750’, Grade II Rock climbing can be just plain Type I fun. You’re outside, with good company, in good weather, using your brain and body to briefly overcome gravity, dancing with the minerals, having a jolly ‘ol time. For whatever reason, granite especially lends itself to this kind of climbing. Joseph contemplating existence on the summit of Mt. Challenger's Middle Peak After scrambling Mt. Challenger’s Middle Peak on day four, Wednesday morning, August 18th, and considering different options for more climbing, we circled back to the south face of Challenger 5 to scope out some pretty neat looking rock. The granite was white to dark with a golden burnt orange in places, peppered with blocks, flakes, and large chicken heads. Fun scrambling to contour back west under Challenger 5's south face Anywhere else these cliffs would be stacked with moderate trad lines. We contoured all the way around the south face until there was nowhere left to go. The southwest ridge dropped off down the imposing west face. Above, a distinct ridgeline ambled up towards the summit. Belay at start of route The route started from a broad, jumbled, and blocky ledge system roughly where the seasonal snow line of the SW ridge ends and the more black, lichen-stained rock begins. If you were hiking directly up the ridge from below, it might be possible to add another pitch for fun, but we cast off from the highest “scramble accessible” point. Climbing on pitch 1 The first pitch went up slabs, followed by a left-facing corner with a laughably fun 5.6 hand crack. Above the corner, a good stance on a ledge set up a short finger crack to another ledge. The rock was exceptionally solid and remarkably splitter, with bomber gear exactly where you might want it. Topping out pitch 1 Starting pitch 2; camp, approach ridge, and Baker River all lower left The climbing went for four more pitches like this, ledgy yet exposed ridge climbing punctuated by fun crack segments. Every roughly 40 - 45m pitch ended at a spacious belay ledge with a slingable horn or solid crack for gear. Views and position on the peak were something to behold. Climbing on pitch 2 Pitch four was the standout, with an improbable and slightly intimidating step right onto the exposed face after a short offwidth pillar. A horizontal traverse with a few hundred feet of exposure led to a straight up crack system culminating in another perfect hand crack, which started at red camalot and ended with a good little stretch of near-vertical number 3 jamming. A final mantel ended on a flat ledge big enough to park a bus on. Awesome exposure and jamming on pitch 4 Huge belay ledge at top of pitch 4 The final 60m pitch cut hard left, off the ridge and onto the west face via an unmissable ledge system. A blocky and slightly loose gully led directly to the summit, with the headwaters of the Baker River 4,000 feet below nipping at our heels and Shuksan and Kulshan swirling in the clouds to the west. Final climbing to the summit As soon as it came in, our weather window was on the way out. Within 15 minutes of arriving on top we were getting engulfed in the mist. We’d left our axes and crampons at the base of the route, and not knowing there was a scramble route off the peak, we elected to rap the south face from the summit and contour back to our gear. In hindsight, had we carried glacier travel gear, we could have descended to the north and potentially gotten back on the glacier, climbed back up to the col, and returned that way. In any case, two raps with two ropes got us off the steep terrain. We retrieved our gear from the base and headed back down the ridge to our 5,200 ft camp, arriving just in time for an incredible sunset as the clouds broke once again. A view of our route from the approach ridge Descending on the approach ridge Back at camp Deproach With the chance of showers in the forecast, we felt good about two summits, a new route, and three nights camped out on an incredible ridge. Now all that was left to do was to reverse miles of steep, trailless wilderness back to civilization. 40 degree huckleberries on the descent Finding the "secret passage" through a major cliff band; we were prepared to rappel, yet managed to avoid it on the way down We camped at the beach for our final evening, near the confluence of Bald Eagle Creek and the Baker River. There was enough sand to walk around barefoot and relax, taking in views of Scramble Creek falls and the North Ridge of Mt. Blum. Surprisingly, someone had camped there in the days we were up high and had left a fire pit, complete with charred logs. One might think the novelty of wading down a river would wear off by the last day of the trip, but surprisingly it didn’t. Out the way out, we knocked over a handful of cairns we made for ourselves on the way in. The only other sign of people we saw was the fire scar and some fishing line at the final campsite, which we packed out. It'd be great to keep it that way for the future. My opinion is this approach is destined to remain in obscurity when “easier” approaches exist, but it is a truly direct and viable way in to the Pickets. Having the right attitude about brush would help immensely. Walking in the river beat the heck out of the alternative Take only pictures, leave only footprints In the days since, I’ve been dreaming about the walls back there, packrafting part of the deproach, scheming about another trip back into the wilderness of the great nearby. It’s adventures like these that, for me, climbing in the Cascades are all about. Many thanks to Joseph for the great company, partnership, use of photos, and willingness to try something different. Gear Notes: Extra shoes for wading, rock climbing gear to #3 camalot, crampons/ice axe for glacier travel Approach Notes: Starts from the Baker River Trailhead. See Tabor and Crowder's "Routes and Rocks in the Mt. Challenger Quadrangle" and Beckey's "Cascade Alpine Guide, Vol. 3" for more approach details.1 point

-

Thanks for your work on this Curt; I'd never even heard of Salami Slab before as it's not in Rattle n Slime and I don't always haunt Mountain Project. It was a fun day out on Sunday; got surprisingly warm on the slabs by the afternoon!1 point