-

Posts

2925 -

Joined

-

Days Won

25

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Posts posted by Rad

-

-

Spicy snice. Nice!

-

A group campsite on Icicle Creek in Leavenworth is probably your best option.

-

16 minutes ago, Off_White said:

I guess it's related thread drift, but I'd be interested in reading more about this trout killing deal, is it because they're planted non-natives? Is there some ecosystem disruption? Not enough mosquitoes?

Trout are voracious predators that disrupted the ecosystem of mountain lakes. It'd be like adding polar bears to pre-schools, but more gory. Hey, do you suppose we could arm those polar bears with AR-15s?

Seriously, though, here's an article on trout in mountain lakes.

-

1

1

-

-

I've learned from experience that if it's green when you find it it'll go back to green if it doesn't get traffic. People will be re-discovering Index routes to the end of time for this reason.

-

1

1

-

-

1 hour ago, JasonG said:

But quantifying risk is Y incidence per X events. We have data on the accidents, but do we know the number of events that it took to produce those accidents? That is what @olyclimber is getting at I think.

The data probably exist, but it might take some work to get them. For example, in MRNP and NCNP backcountry climbers are required to register, so this provides data on the number of outings. This can be compared with accident data. In avalanche papers I seem to recall data about accidents per user-day. There will be cases where the user-days are not available or harder to get, but that doesn't mean we should throw up our hands and say there's no data.

-

2 hours ago, genepires said:

well of course it would be near impossible to make a even half decent number...

There are numbers, there are statistics, and there are articles on climbing accidents. You can read ANAM and put together your own chart if you wish. Claiming there are no data or that risk can't be quantified is lazy at best and inviting trouble at worst.

To Bob's comment, my kids and I talk about how much luck and skill are involved in the games we play. Chess is all skill. Chutes and Ladders is all luck. For the ones in between, we try to assign a percentage. Settlers of Catan, for example, might be 70% skill and 30% luck. Cribbage might be 70% luck and 30% skill. Climbing accidents can be viewed this way as well.. Some are 100% human error (rapped off end of the rope), all luck (a stone falls down Everest and beans poor Ueli Steck), and many are something in between (getting struck by lightning in an alpine thunderstorm).

I advise, support, and invest in biotech and medtech companies. There are at least as many types of risk in these ventures as there are in alpine climbing. People's careers, reputations, and money are on the line, so we can't just throw up our hands and say, "I don't know" when it comes to evaluating risk. We try to break down the different types of risk, work to see what can be avoided or mitigated, and determine when there are unacceptable risks. It's never easy, and we still get it wrong, but we analyze as much as we can in hopes of making the most informed decision we can.

In climbing, we don't get to learn from our mistakes very often as a single error can kill us, so it's important to learn what we can from the mistakes of others. Adding statistics and probability into these analyses allows us to learn from a larger data set than just a few examples.

-

1

1

-

-

6 hours ago, montypiton said:

5.4 will limit you . northwest buttress on Stuart goes about 5.0 if you stop at the ridge crest. to continue to the summit, finding a 5.4 line on west ridge of Stuart might be tricky, likely more like 5.6.. north ridge of stuart (50 classic climbs) goes about 5.6 northwest buttress and northeast couloir (possible ice or snow) on Argonaut go about 5.6. cross to the south side of mountaineer pass and the south face of Argonaut may have a line at 5.4. east ridge of Sherpa from mountaineer pass goes about 5.5. northeast face of false summit on Stuart supposedly goes at 5.6. possibly a 5-easy line on northwest face of Colchuck, but that is undocumented as far as I know. all of these routes will have some snow on approach, even in August. I've climbed ice in Argonaut's northeast couloir Labor Day weekend.... all of these would be fairly long days for a family group (unless your family name is Lowe), but none are terribly committing - escape/retreat would be reasonable in most cases. do take fishing gear for Stuart Lake.

It should be noted that most or all of these routes involve mountain navigation and route-finding skills. If the route is 5.4 but you start up the wrong crack or don't cross the crest at the right point you can quickly find yourself in terrain that is 5.9 or harder.

-

I agree with everything said above. In my experience, carrying a rope, rack, harness, helmets, and related climbing gear adds a lot of weight. You could do trad multi-pitch lines in Icicle Creek canyon before or after your trip and be lighter and happier without lugging that into the back country.

Note that the tiny lakes above Stuart Lake are surrounded by incredible boulders and there are plenty of peaks nearby to scramble/climb. There is an unofficial trail that leads up there. Might be helpful to have a topo to guide you.

Enjoy!

-

2 hours ago, olyclimber said:

Ryan didn't share any TRs here, but he did have a pretty good contribution to the Random Climbing Partners thread (best of cc.com)....

And the entry right after Ryan's is from....Marc-Andre Leclerc.

-

I do think attempts to quantify risk are valuable, even if they are flawed, because a better understanding of the risk/reward ratio might change a few people's minds, change their behavior, and perhaps spare them from a life-changing/ending accident. Or it could help them enjoy hundreds of days of climbing, skiing, or other reportedly risky activity without a serious incident.

Unfortunately, many of us don't do a good job of evaluating statistics because we draw conclusions based on stories from people we know or read about and ignore or misrepresent statistical data on the subject in question. If someone says they have same risk of dying in a rappelling accident as being hit by a bus in a crosswalk should you believe them? What if your wife asks you to quit alpine climbing because it is too dangerous and take up paragliding instead? How do the dangers of these compare with texting and driving? What if someone could show you data that the chances of a rappelling accident go up 10x if you don't tie knots in the ends of your ropes? There will always be unknowns in climbing, but attempts to quantify risk can make us both wiser and safer. Here are two illustrations from other parts of life:

If your doctor tells you that you late stage Pancreatic cancer, have a 98% chance of being killed by it within 2 years, and have a 10% chance of responding to a new drug that could allow you to live 10 years but will definitely make your next year miserable and drain your savings, would you get the therapy? Do you think you will "beat the odds'"? Will you go for the experimental drug? Do homeopathy instead and focus on getting the best out of the time you have? Understanding the statistics can lead to better decisions and better quality of life.

The act of building a mathematical model for your personal finances, even if it is too simple and even if it is wrong, is valuable because it forces you to write down and quantify the assumptions that go into the model. Then once you understand the model you can change the assumptions, variables, and inputs and see what happens in different scenarios. Should you retire at 60 or 65? Get disability insurance? Can you afford to take a year to travel? Should you pay down loans, take that expensive vacation, max out retirement investment, or fix that plumbing leak? Everything has costs and near-term and long-term consequences. Quantifying these can be informative and lead to more informed decisions and a better life.

Building a simple model of risk in climbing, even if it is imperfect and incomplete, could lead to better climbing decisions, better conversations between climbing partners about risk, and perhaps fewer injuries and deaths for climbers. That said, if you read ANAM and can learn to avoid making the top three types of human errors you will be much safer for it.

Bring on the math!

-

1

1

-

-

@W your post is one of the most powerful and profound pieces of climbing writing I've seen in a long time.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts and for showing us what it means to live with intention.

-

Play with this calculator and you'll see that even if the chance of a given bad outcome on a single day is low if you roll the dice long enough the chance of that bad outcome happening can be quite high. Simple risk model from SJSU

A survey would be interesting, but I think it will yield anecdotes more than useful data. For larger numbers of anecdotes and data check out ANAM issues. Patterns emerge pretty quickly, and there are stats available. I think this should be required reading for all outdoor climbers.

-

1 hour ago, dberdinka said:

More interested in the idea of why and should we applaud such high levels of risk taking.

I think this has more to do with media coverage of climbing than anything else. In today's world, clicks/likes = dollars, so this drives the media machine. Look at Loren and Jens' TR on Jberg. It drew a lot of clicks, even if a fair number of people talked about how it was an unwise risk. Would Into Thin Air have become a best seller, or even been written, if everyone came back alive? No. Death and death defying feats sell.

You may recall that Clif Bar backed out of sponsoring climbers who engaged in free soloing. This included Potter, who is now dead, and Honnold, who has gone on to become a mega-star known for free soloing.

That said the general public is still quite ignorant about climbing and doesn't understand that the risks of climbing the Dawn Wall are actually pretty low compared to many other kinds of climbing. With Honnold, everyone understands that if he falls he dies. Ueli Steck was thought to be the Swiss machine who was super safe, but they didn't factor in that he was doing his thing in the mountains, where objective hazards are higher than on the rock walls of Yosemite.

I agree with others above that climbing needs a better culture of rational risk assessment and management. These may be better in other fields, such as avalanche safety and paragliding (apparently). One challenge is that climbing has way more things that can go wrong and hence risk factors to assess compared with avalanche safety. An organization like the Mountaineers could play an important role in this education.

-

I find risk fascinating. It seems that humans are often irrational when it comes to risk assessment and risk management/mitigation. I don't have formal training in this area, so others may have expert opinions to contribute that are more sophisticated than mine, but here are a few thoughts.

It seems that risk involves the following factors:

A - inputs: intrinsic and extrinsic actions or non-actions. Intrinsic refers to our own actions or non-actions whereas extrinsic is everything outside us, including the actions and non-actions of other people as well as acts of nature and other non-human actions. Note that extrinsic inputs include both objective hazards like avalanches as well as other humans who may drop things on you or trigger avalanches above you).

B - Outcomes, good or bad.

C - Probabilities of outcomes given certain inputs.

Note that you can only affect A, and even then your direct control is limited to intrinsic actions/non-actions.

Risk assessment is about understanding the relationships between A, B, and C.

Risk mitigation/management is about changing certain inputs in an effort to achieve or avoid certain outcomes. Classically, the ways to deal with risk are to avoid, reduce, transfer, or accept it.

A few quick thoughts, each of which could be its own essay:

1 - There are risks, rewards, and consequences in everything we do. Social. Career. Financial. Physical. People rarely think about all of these.

2 - There is a continuum of consequences in many situations. Life is rarely as simple as fell/didn't fall.

3 - Consequences can come from in-action just as easily as from action.

4 - There may be time-dependent, delayed, or cumulative effects that complicate the ability to connect 1, 2, and 3 in a causal way. For example, not exercising or smoking might have no discernible immediate health consequences, but their impact can be devastating if they become a pattern. Many people are unable or unwilling to acknowledge the long term consequences of the myriad of behaviors they perform.

5 - Skill, speed, experience, planning, gear, and strength can be inputs. Alex Honnold is far less likely to fall off 5.12 than me.

6 - I find climbing interesting because it forces us to think about risks. The ability to rationally assess and manage/mitigate risks can benefit us in every facet of our lives. I hope my kids learn these skills in climbing or another facet of life.

I'm still learning, that's for sure.

-

Damn. Like many, I was hoping for the best but expecting this outcome. Tragic.

-

20 minutes ago, billcoe said:

I apologize and mean no disrespect. It's tough, as we all know, nothing I say will change any of that. There are a lot of nuances which we miss in making bold declarative statements, it's harder to type it than say it. I'll bow out now with that final note.

Bill, you haven't said anything wrong and certainly don't need to apologize. We'd like you to stick around cc.com even if you're done in this thread. Peace

-

1

1

-

-

It doesn't need to be either or. We can grieve the loss of an inspiring climber AND shake our heads at the risks they took. Dean Potter is a case in point.

I, for one, am not past the grieving stage for Marc, even though I never met him. His loss tears a big hole in the fabric of our local climbing community.

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

-

Powerful stuff, Jay.

It's generally not the deceased who suffer longest, but the ones they leave behind.

-

2 hours ago, genepires said:

for a while I have been trying to figure out the mathematics with a probability of risk.

Gene, it's easier if you flip it around. The chance of nothing happening in your model is 99%, or 0.99. The chance of nothing happening two days in a row is 0.99 x 0.99 = 0.98. The chance of nothing happening a hundred days is 0.99 to the 100th power. If you calculate this you get 36.6%. Which means there is a 63.3% chance something bad will happen if you climb 100 days with each day having a 1% chance of that bad thing happening.

-

I think part of the reason accidents are disturbing to climbers is that we are forced to acknowledge what we try not to accept: it could happen to us. We explain to ourselves and to each other "that would never happen to me" and "I would never make that mistake". But if you read ANAM you know we can all make mistakes and eventually luck catches up with you.

Mountains are inherently dangerous, but the danger is an essential part of the game for most of us, even if we all have a different tolerance for risk. Part of climbing is about conquering fear, and seeing Honnold or Leclerc is impressive for the mind control they've achieved. We can admire that, even if we would never take those risks ourselves.

-

From LeClerc's blog on his Emperor Face ascent on Mt Robson:

"It was now my fourth day alone in the mountains and my thoughts had reached a depth and clarity that I had never before experienced. The magic was real.I thought to myself that the essence of alpinism lies in true adventure. I was deeply content that I had not carried a watch with me to keep time, as the obsession with time and speed is in fact one of the greatest detractors from the alpine experience. I was happy that my entire experience had been onsight, on my first visit to the mountain, and that the route had been in completely virgin condition. One of the greatest challenges of mountaineering is in dealing with the natural obstacles the mountain provides. So often in modern alpinism, routes will be fearsomely difficult for the first party of the season, and then once the obstacles have been cleared, a track established or the ‘tunnels’ dug it becomes easy for those who follow.Climbing routes that have been cleared, with an established track,simply in order to attain the summit, or keeping time in order to set records is in fact reducing the adventure of alpinism more to that of a sport climb, and strips the route of its full challenge making it more of a ‘playing field’ of a team sports athlete or like a barbell at an indoor gym where a jock tries to lift his personal best.As a young climber it is undeniable that I have been manipulated by the media and popular culture and that some of my own climbs have been subconsciously shaped through what the world perceives to be important in terms of sport. Through time spent in the mountains, away from the crowds, away from the stopwatch and the grades and all the lists of records I’ve been slowly able to pick apart what is important to me and discard things that are not.Of course the journey of learning never ends but I’ve come to believe that the natural world is the greatest teacher of all, and that listening in silence to the universe around you is perhaps the most productive ways of learning. Perhaps it is not much of a surprise, but so often people are afraid of their own thoughts, resorting to drowning them out with constant noise and distraction. Is it a fear of leaning who we actually are that causes this? Perhaps so many of us are afraid to confront our own personalities that we go on living in a world of falseness, filling the void of true contentment by being actors striving to be perceived by the world around us as something that we ‘supposed to be’ rather than living as who we are."-

1

1

-

-

Oh, I really hope this is just a shiver bivy followed by a cold walk out and an awesome story to read in Alpinist. Fingers crossed.

-

It took me just 15 minutes to create this TR, copying and pasting from content I had.

So easy! Thx for the awesome upgrades to CC.com!!!

-

1

1

-

-

Trip: Sedona - Mars Attacks!

Trip Date: 11/20/2017

Trip Report:Having an adventure that pushes you beyond your comfort zone is great....unless it's your daughter, a friend's child, and your wife on the other end of the rope when things go sideways.

When my wife and I started dating we made a deal: I’d learn snowboarding, which she loves, and she’d learn climbing, my passion.

We shared some good times on the rock many years ago, but in recent years we haven’t climbed together except in the gym. My daughter, now 12, started climbing early, but she’s only been outdoors a few times, on top rope or following single rope pitch bolted climbs. Dan, a close family friend, has really enjoyed the few times he’s climbed and was eager to do more. A quick trip to Arizona, a few hours from his family, provided an opportunity.

I figured we’d just climb on some short, easy routes in the sunshine. I’d walk to the top, set up an anchor, toss down the rope, and belay. But then on our hike to Devil’s Bridge we saw climbers on a sun-drenched buttress across the valley. Gaping from flatland, I realized I was now the tourist gazing up at climbers instead of the climber looking down on tourists. I’m not ready to make that transition. So I did some research and looked up the route….

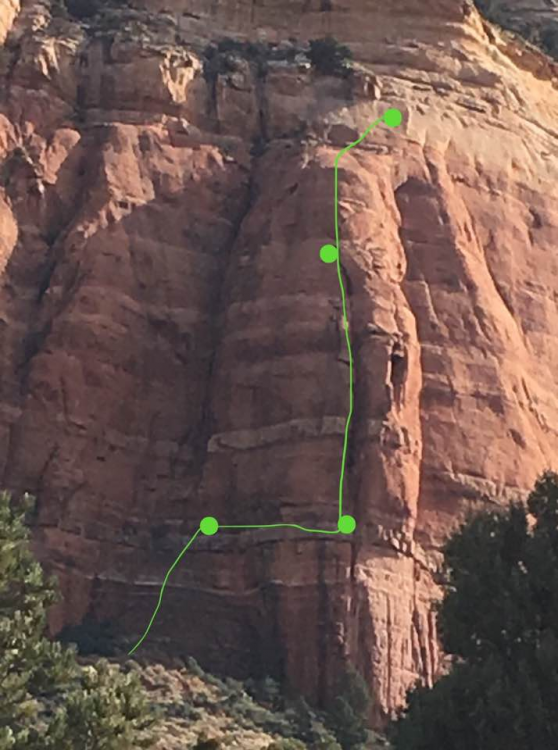

The climb we did is the prominent buttress in the upper center of this shot.

It was Mars Attacks. Four pitches of 5.8. Each one holds a different mental and physical challenge. 400 feet of climbing with a traverse and two double-rope rappels to get off the top.

I might be pushing too many envelopes at once by bringing three inexperienced climbers up the route, but I was confident I could get us safely up and down (green dots mark the belay stances at the top of a pitch.) …

The approach started on the familiar trail to Devil's Bridge before heading North to a wash and a faint climber's trail around a cliff to the base of the wall. Somewhere in there we got off route and had to dodge some ankle-biting cacti, but we found our way...

The trail contoured above a small cliff with great views back across the canyon...

At the base of the wall, we got our gear together: two ropes, harnesses, and a variety of climbing gear. My daughter sticks to the wall even without her climbing shoes.

The crux of the opening pitch is a holdless low-angled slab where you must trust your feet and the rubber in your shoes, balance on the balls of your feet with no handholds at all, and BELIEVE in order to climb.

I lead the first pitch, scampering up moderate climbing to a high first bolt. 20 feet later I hit the crux slab. I puzzled for a bit, but hundreds of ascents in recent years have worn off the tiny features on the rock, which is now smooth and blank. I tried one sequence and started sliding, so I grabbed the protection to stop. We didn’t have all day, so I pulled on the quickdraw and stood on a bolt to get past the crux. I climbed the rest of the pitch clean and made it to the belay, an airy stance below a giant hueco.

The others came up behind me, with a bit of tension on the rope to help them through the crux. They all did great on the rest of the pitch.

At the belay there was a giant hueco worn into the rock by thousands of years of desert winds. It was a comfy spot for some to take off their shoes and take in the view.

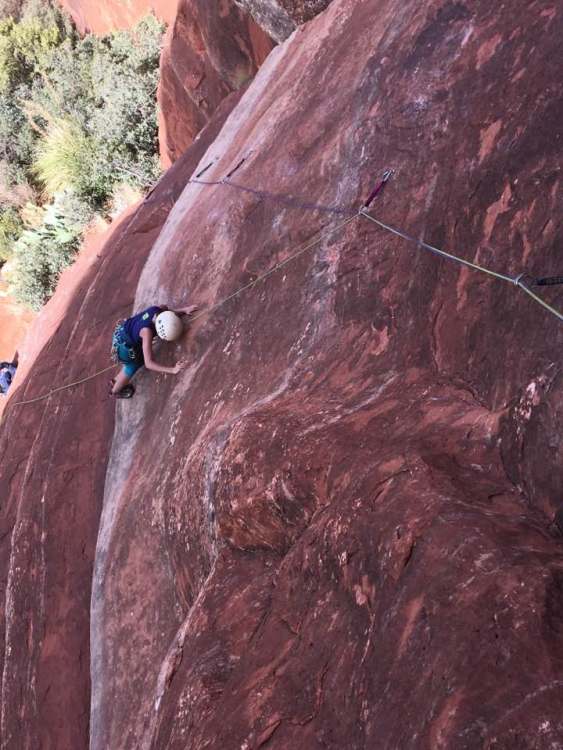

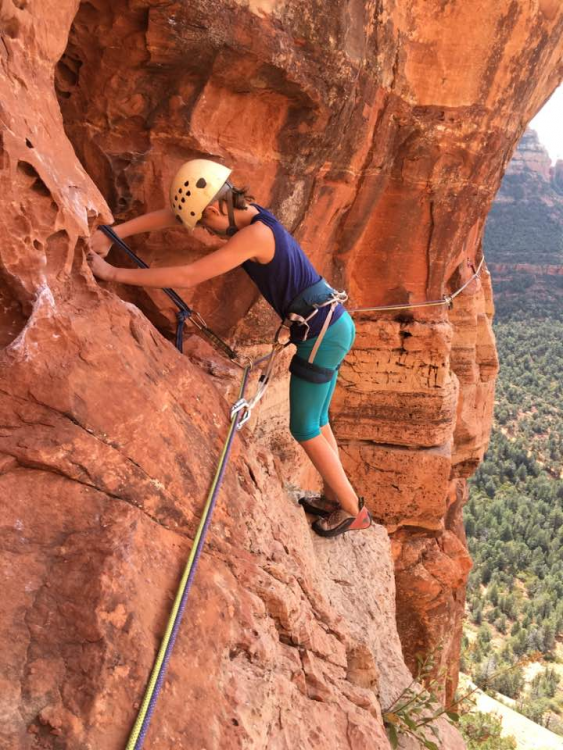

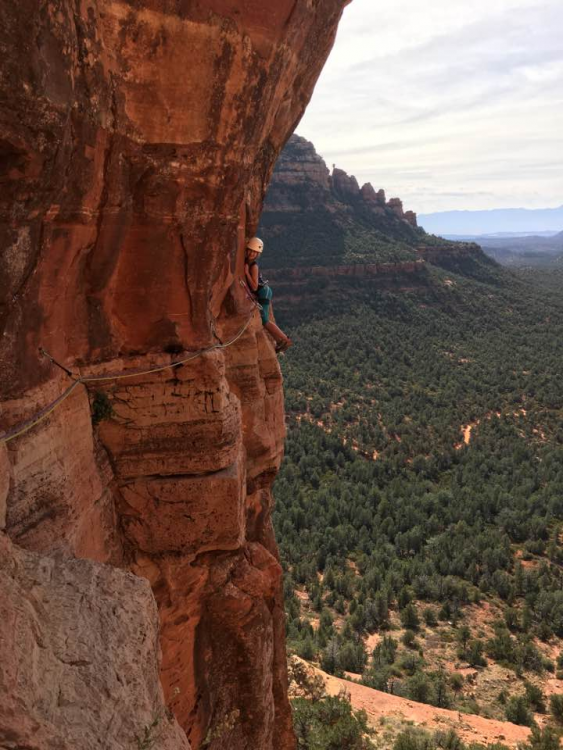

The second pitch is a horizontal traverse along a limestone dike in the middle of the red sandstone cliff. There are good holds most of the way, but the exposure is incredible. The limestone band protrudes from the cliff because the softer sandstone below it eroded away, leaving you staring down between your toes to the ground about a 100 feet below.

If you fall, you will dangle in open space and might be unable to re-gain the limestone.

I had a hard time sleeping the night before the climb, going over in my mind how we could all safely climb this pitch without risking a pendulum fall into space.

First, I lead across.

A came next, clipped to both ropes via slings but not tied into either one. Via ferrata style. She had to unclip one sling at a time to get around each bolt. If she fell she'd still be attached to both ropes and could easily get back on the wall.

Here she is moving past one of the seven protection bolts that were placed by the first ascent party in 2000.

Resting in a thin section. The Devil's Bridge trail is visible behind her.

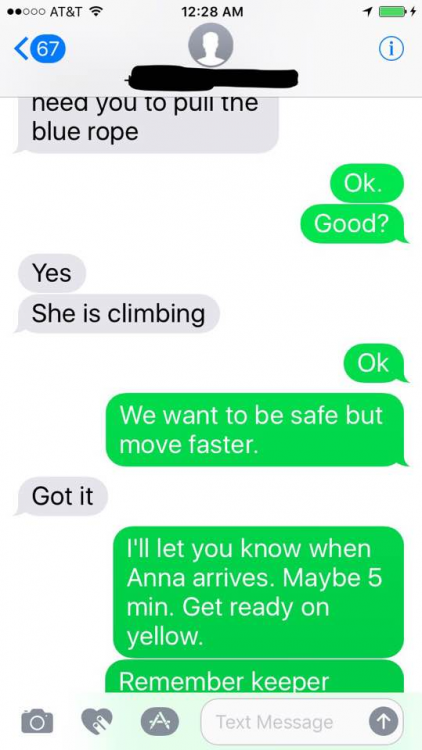

It was impossible to communicate on the second and third pitches, but we had just enough cell signal for texting. Here's a snapshot of our communication.

We had a clear plan, and I knew Beth had enough climbing experience to belay me and make sure A and Dan could set off safely.

Arriving at the end of the limestone band.

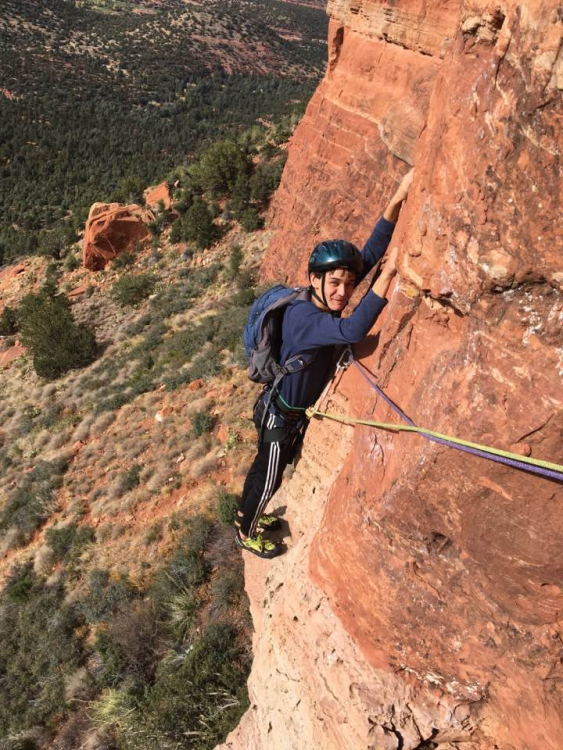

Dan coming across second. He was tied into the end of the yellow rope and had one leash clipped to the blue rope, which would keep him from dangling in space if he fell. He didn't.

Beth came last, tied into the end of the blue rope. She unclipped our gear from the bolts. She was totally solid and didn't fall.

Two pitches down. Two to go. But we were moving slowly. I was having to check everything and do all of the work to keep the ropes and protection organized and untangled. We were always very safe, but we were slow. And it would catch up to us...

The third pitch is a dark red vertical chasm, a slot, like an open book. The steep sandstone on one side of the corner has been worn by wind into crazy pockets called huecos. Some are tiny, others are large enough to climb into, and you’ll find every size in between. Then there is the crack, which varies between the width of a finger and a slot several feet wide.

To ascend you must use a wide range of crack climbing techniques that are not very intuitive to the uninitiated, including hand and foot jamming, palming smooth walls to move your feet up in a stem, using your palm and upper arm in opposition while your arm is bent like a chicken wing in a wide crack, lie backing on a sloping rail, and more.

I placed cams at wide intervals for efficiency and because I didn't have a lot of gear. Fortunately, the climbing wasn't too hard and the tough bits were well protected.

Sometimes an accidental shot can yield an interesting image. This is looking back down from high on the third pitch.

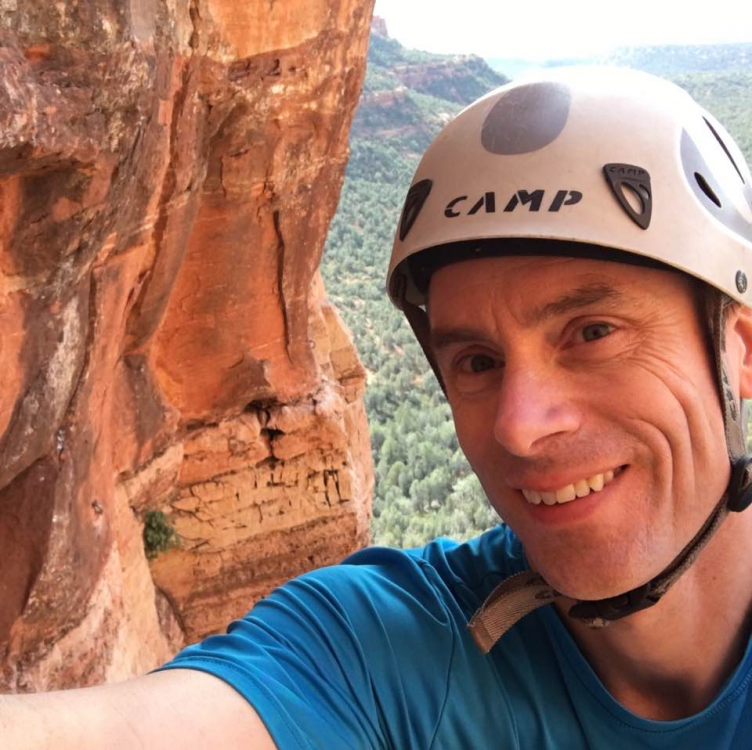

Lead climbing brings the mind into sharp focus. The world's deluge of distractions is swept away in the face of the immediate situation.

The views from high on the wall were stunning, the air was still. At one point, a raven swirled on rising currents and circled our group curiously, wondering what these noisy, vulgar beasts, whose brethren provide such rich garbage down below, were doing up here in the land of wind and stone.

The fourth pitch combines some awkward crack with slab and face moves and ends with a long, unprotected section of low angled rock where a fall by the leader is unlikely but would be bad.

Dan climbed the final section of the final pitch...

just as the sun was just about to head down below the horizon. Night would soon be upon us, and we still had to get down.

Here we are about to make the first rappel, which runs down a clean face on the far side of the buttress. You can see the trail far down below us.

I rigged everyone's rappels and then headed down first to look for the next bolt station just as the sky glowed orange and red in a beautiful sunset. But we didn't have any headlamps, a cardinal sin I acknowledged before we left the car in the morning. I've rappelled in the dark, but never without a headlamp, and I've never had inexperienced climbers rappel in the dark without a light. Good thing they're all strong of mind.

I rappelled down the vertical face in gathering darkness, looking for a three bolt anchor mentioned in the guide. We'd never seen this part of the wall as it's on the other side of the buttress we climbed. And here's where I pushed things a bit farther than I'd intended, because I never found the bolts. I looked left and right between 45 meters to 55 meters down our 60 meter ropes. Nothing.

Swinging back and forth across a blank cliff in near darkness without a light was a bit unnerving even for me. Our ropes wouldn't reach the ground, and although I could have ascended back up to our anchor above, it would have been very slow and difficult.

We could have rappelled back down pitches 4 and 3 and then to the ground from there, but I'd read multiple stories of people getting their ropes stuck in the cracks we'd climbed, so that was surely a last resort.

Instead, I swung over to the crack shown here and built an anchor using a few cams I just happened to still have on my harness. Truth be told. I'd put most of the rack in the pack my wife was carrying. Fortunately, I had the pieces I needed. Luck was with us. I clipped myself into this unplanned, makeshift belay spot and yelled off rappel so the others could come down to me.

I held the rope ends as first A, then Dan, then Beth rappelled down in the dark to join me in this corner crack 150 feet off the ground. I pulled them each over to me from the blank face out right. We were safe, and I kept reminding them of this. The stars came out on a brilliant night.

I was able to tuck my phone into my pants by my belly and shine light on our belay as we rigged to descend. This time I would just lower them one at a time to the ground. Thankfully, the rope reached. I lowered Beth into the darkness first, explaining that she'd need to climb up to the large ledge below us if the ropes didn't reach the ground. But she made it.

We were safe, but well beyond our intended plans. Then again, that's where adventure begins.

We made it down and used the light of my phone to hike out on the trail. The evening was calm and still and the Milky Way guided us back to the car.

I ended up leaving two cams behind. Over the years I've gathered gear from the misadventures of other climbers. This time they can benefit from ours. No worries.

An adventure to remember!

Gear Notes:

Headlamp would've been nice

Approach Notes:

Follow the trail-

3

3

-

1

1

-

Beacon Rock Stories

in Oregon Cascades

Posted

@dpasquinelli Thanks for sharing. Hopefully some of those who climbed with him can join you. In any case, climbers will be passing over him every time they are out there. RIP Ken.