Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 01/05/23 in all areas

-

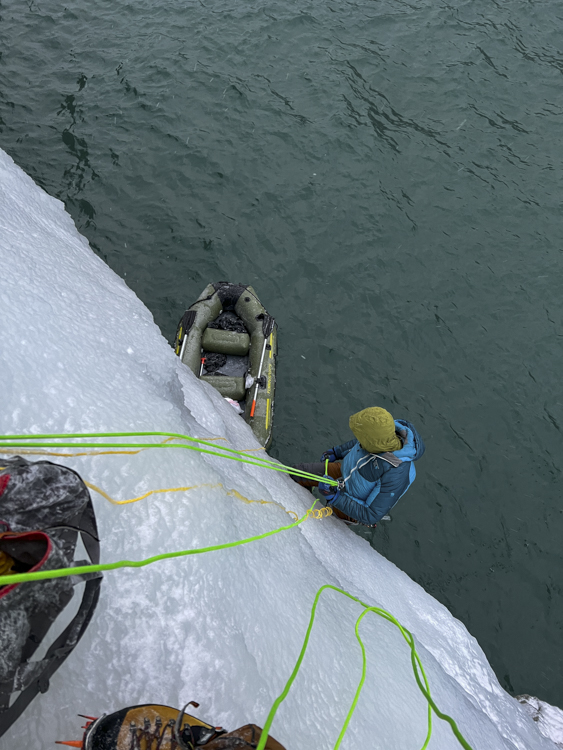

Trip: Seton Lake - FA-Lieutenant Dan's Aquatic Death Ride - 450m 4+ Date: 12/16/2022 Trip Report: Ice climbing around Lillooet has been on my to do list for a few years now. Just needed the right conditions and a stoked partner. This December it came together. Doing some research on the area, Zach Krahmer and I saw that an epic looking and unclimbed line had come in at Seton lake and it seemed too good not to take a shot at. We'd be there Thursday night, and Friday looked to have the best weather conditions to go for the route. The West Coast Ice guidebook advises climbers to “canoe down the lake about an hour to the climbs” on Seton Lake. Jesse Mace and Bruce Kay used a canoe, but recommended a row boat in their report for the FA of Piss 'n Vinegar. Jesse highlighted a few concerns with a canoe including potential capsizing in choppy weather and damage to the boat while climbing (from falling ice, and hitting the cliff if winds picked up as you climbed). Coming from Oregon, we looked into canoe rentals near Lillooet and found none given the season. After almost giving up due to feasibility concerns, a friend of Zach’s offered to loan us a rowboat style 2-person raft made of ripstop material. Not only would it fit in the car on the drive up, but it might be more stable in choppy water, and once we unweighted it to climb, it would be less likely to be damaged by contact with the rock cliff. On the face of it, there seemed to be some sensible advantages over a canoe. However, an obvious question remained → how to start ice climbing with crampons from an inflatable raft in an ice cold lake surrounded by steep rock cliffs? Would there be a place to safely step off the raft onto the climb without crampons that wouldn't result in a slip into the frigid water below? Jesse's trip report mentioned (jokingly) that a gun might be better than a life jacket if one were to fall in. It was hard to tell from the compressed pictures we’d seen online to know what would be waiting for us. We arrived in town Thursday evening and Zach drove us straight to the lake knowing that we might be paddling back the next night in similar conditions. The waves were nearly non-existent and the water almost completely calm. Checking the forecast we saw the next night's forecast was similar, which gave us what we needed to make a decision. We decided the next morning we would paddle out and see how the raft to climb transition looked. We hoped for the best, but knew very well we might be paddling right back to where we started. Prepping the boat in the early morning hours Ready to disembark The next morning we arrived in the dark after checking forecasts again. We inflated the raft and launched into the calm water. It was a peaceful paddle and we saw four eagles on the way out, one of them diving into the water for its meal. We took note of the other climbs that were coming in nicely this season. Looking back 2 km to our put in from aboard the raft. Comedy of Errors | Deliverance / Squeal Like a Pig | Fishin' Musician Fishin' Musician on left with Winter Water Sports in the distance. The climb! After 5-6 km of paddling, we neared our objective. We were dismayed by what we saw. The wall was far too steep to step onto safely without crampons. We paddled past the climb for a new perspective in hopes of seeing something nearby that could get us established, but found nothing. Passing by again, we took a longer look at the thin layer of ice that came down close to the water's edge. The ice nearest the lake water was partially delaminated from the rock, but seemed to be solid just a little higher. We devised a plan. With Zach holding dynamic tension from a cam at the rear of the boat, I would reach over to the sheet of ice and place ice screws, attach slings to those screws and then step into the slings with cramponless boots. This would get me high enough off the water, and far enough from the raft, so that I could attach crampons and get moving. Because the ice closest to the water was questionable, I knew I had to get a screw as high as possible. I leaned over kneeling carefully and started to place the first 10 cm screw. After just a few turns, the screw bottomed out onto the rock below. Damn. Surely I’d just hit an unlucky bit of thinner ice. “How easy this all would be if I just had my crampons on!” I removed the screw and placed it again, once again hitting rock after a few turns. Not willing to take a chance on such a marginal placement, I reached as high as I could while Zach steadied the raft. From this precarious stance, I managed to get a screw about 7cm into the ice. Knowing the failure mechanics of partially driven screws, and knowing I would be delicately standing in the sling rather than taking a dynamic fall, this seemed adequate to get started. I clove-hitched into the first screw to safeguard a higher reach and placed another screw. It wasn't great either, but deep enough! Using my tools I carefully stood up in the raft and got a foot into the first sling. I gently weighted it and saw no sign of failure. I stood up, and placed my foot into the other screw’s sling. With all my weight now on the wall, I reached higher to thicker ice. I fired in another screw and clipped into it. Now I was far enough from the raft to put on crampons safely. It ain't easy touching your toes while hanging off a screw and wearing a life jacket, but after a few minutes of uncomfortable gymnastics, the crampons were on! Now that I was properly ready, I shot up to a position above an overhanging cove where we would stow the raft. I built a v-thread to attach the raft and belay Zach up. Moments later we'd hauled up an array of “oh shit” gear (hot broth, food, bivy gear, dry clothes, warmers and anything else we might need if the boat failed) that had been stowed in waterproof bags in the raft. Zach cleaned the boat and made his way up to join me at the belay. We were finally ready to climb but the extra care we'd taken in exiting the raft had used up a considerable bit of time. Weighing the various risks, we'd prioritized fastidious attention to detail during this tricky and unfamiliar portion of climbing instead of schedule, and it showed. We were starting the climb at 12:30pm. We discussed and agreed - we weren't sure how far we would make it before we ran out of daylight, but the first half of the climb had looked relatively easy, so maybe we could make up time? I started up the first pitch which cuts over and then up a small section of ice that spills over and connects the starting cove and the primary flow of ice above. This first section turned out to be excessively wet, chandeliered ice with no real options to avoid the flowing water. I did my best to move quickly, and soon enough I was above the cove, an anchor was built and Zach was brought up. Above us was a long stretch of multiple 70m pitches of WI3 before steepening into the main headwall. We had twin 70m ropes so I knew I could cover a fair distance with each pitch, just had to move smoothly and efficiently! I took off. Although often wet, the climbing was straightforward, and soon enough I was 70m above Zach ready to set up a belay. “At this rate we stand a chance to make up time!'' I thought. But my hopes were quickly dashed. As I built the anchor and started to pull the weight of the two 70m ropes, I found we’d encountered an unfortunate new challenge. The rope was completely saturated and freezing in the cold temps. Not only was this creating a massive amount of resistance to pull the rope through my device as it sheared off the thick ice, but since the ropes were so coated in ice they were nearly impossible to grab with my glove, often slipping right through as I tried to pull in slack. I worked hard to use whatever tricks I could think of, but I was not able to pull in slack quickly, slowing Zach’s progress substantially. Finally Zach was at the belay and I started up the next pitch. On lead I was able to move relatively quickly, but at every belay the icy rope recoated, and seemed impossible to pull though the belay device. It wasn’t getting any better as we continued on, and it was taking a toll. The belaying was literally harder than leading the pitches! Around halfway up the wall the sun began to fade, and we knew we'd have to make a decision on whether to continue on or descend to our vessel. Winds were non-existent and temps were comfortable as night fell. The biggest challenge continued to be the icy belays, but conditions were downright pleasant, and route finding with a headlamp was going well so we decided to continue upward. The main headwall is a series of roughly pitch length ice steps, that each obscure the step above (probably exacerbated by the limitations of our headlamps). So at the top of each step we'd be sure we were on the last pitch, only to find another full rope length of climbing above. Slowly but consistently we checked in and continued on. The late night and cool temps brought some neat Hoarfrost. Similar to this branch, the hoar frost binded horizontally to many of the ice pillars on the upper portion of the climb. Way behind schedule but in good spirits, we topped out and built the first v-thread, preparing to descend. It was a beautiful night, and surely raps couldn't be as hard as the guide mode belays! Late, but in good spirits! Descending was relatively smooth with the exception of the rope freezing to the cliff a few times and a route finding error where I went too far to climber's right and ended up in the wrong drainage. Accidents seem to happen on the way down when people start to lose focus or rush, so we did our best not to do either, slowing and safely working our way down the wall. Before too long we were back at our stash of gear, drinking from Zach's thermos and eating snacks, our raft floating safely in the protected cove below. So far so good, now we just needed to get back into the boat and paddle out! We could hear the sound of waves below us, sounding larger than what we’d experienced on the way in. We tried to make out the lake conditions with our headlamps, but the dark water seemed to reflect almost nothing. We’d taken far longer than we’d anticipated to get to this point, and now the sun would be up soon. Feeling warm and good, we figured we might as well relax for a minute, taking our time to eat and drink, as daylight would make navigating the lake easier. Shortly after sunrise, as we prepped for the last rap into the raft, Tyler Creasey arrived transporting another party in his boat. From his boat, Tyler offered for us to come aboard to relax and enjoy his heated cabin for a few minutes once we got off the climb. We’d spoken to Tyler the previous week and ran into him the night before at the Cookhouse–awesome honey garlic wings by the way! Tyler is offering his services to climbers for the first time and we’d recommend connecting with him if you are interested in his boat. We removed and safely stowed anything sharp, put life jackets on and rappelled into the raft. We’d intentionally left the boat under the cove to protect it from ice fall, but this also meant that it was partially below the wet ice flow. I was in the boat first and found everything in good shape, but some water had accumulated in the bottom of the boat. Not enough to impact travel, but enough to slosh around and get my boots wet. “Oh how pleasant” I thought. Zach cleaned up, rappelled into the boat and we were off, leaving behind only the v-thread. Although I was anxious to get back to the car, we agreed it would be fun to take up Tyler on his offer and relax for a minute on his boat. Tyler was hanging out at the base of Winter Water Sports, occasionally trolling eastward toward the parking lot to prevent the wind from blowing him too far west. After we boarded we got to benefit from one of these trolling sessions, as we sat chatting with Tyler for about 15 min. Before long, Tyler reached the furthest east point he planned to troll to and let us know this was our stop. We climbed back into the raft and started paddling again. It was 9:59am as we pushed off from Tyler’s boat. We’d been advised about the risk of winds picking up around 2pm, which would have left us plenty of time, but as we paddled towards the car our luck wasn’t so good. Winds were increasing and our forward progress began to slow. As more time went by, the wind increased, we slowed and the cycle began to reinforce itself. It seemed our progress would eventually be stopped if winds continued to increase, so we opted to cross the lake and travel on foot the remainder of the way back. A railroad track runs the north side of the lake. We knew dragging a boat wasn’t going to be easy, but at least we wouldn’t be at risk of being blown further west, away from the parking lot. We arrived at the far side of the lake and pulled the raft onto shore. The boat wasn’t light, but slid along the tracks quickly. Just before the parking lot there is a narrow channel of water separating the railroad tracks from the dock about 55 meters across. We approached the channel and assessed the best place to put in and cross (taking care to stay west of the dam inflow). At this time, Tyler’s boat drove back to the docks, only to quickly turn around and head back up the lake. Tyler’s boat turned again and headed straight toward us. I figured Tyler was going to take the opportunity to bust on us for doing things the hard way before heading back to check on the other climbers. Instead, he conveyed a message that immediately crushed me. Someone had called search and rescue on us. I was in complete disbelief. How did this happen? We’d literally just been hanging out with Tyler on his boat joking a few hours ago and in good spirits and he is the guy that does SAR on the lake. Later we would find out that when SAR called Tyler after we’d departed his boat, he told them he’d just seen us, and if they waited we’d be back to the dock soon. While I am frustrated they didn’t heed Tyler’s recommendation, I understand why. I know SAR is under significant pressure in circumstances where a rescue is potentially needed and choosing not to take action always has some risk that a negative outcome will result. We both have a strong opinion regarding SAR calls. Specifically, we believe SAR should only be used in cases where death is imminent or long lasting bodily injury is otherwise inevitable. I despise an attitude amongst some that seem to believe that SAR is who you call when you get tired, or things get hard. If you don’t have high confidence that you can get back or get down, then you don’t have business pursuing that objective. Upon our return to the base of the climb, if the boat had been destroyed, and we had no other way across the lake, we would have climbed the route again, connected to Seton Retask Road and hiked the 27km back to the car. It wouldn’t be easy or pleasant, but harder things have been accomplished by people who’ve set their minds to them. I don’t see the world of adventure as a theme park where I can hit the big red EMO switch on. And yet here we were, standing in front of a uniformed Canadian police officer, requesting that we get on Tyler’s boat to be escorted across for the remaining distance that I could nearly throw a rock across. We reluctantly complied and soon enough we were back at the car. We talked with the SAR members to understand what had gone wrong so that a similar mistake would not be repeated. We’d thought we were doing things right. We had met with Tyler the night before and discussed communication during the climb. Zach had been communicating with Tyler (the very person who would have been called in a SAR event) during the climb, providing him with updates on our progress and general wellbeing. Zach had an inreach mini that we could have used at any time if a real problem had arisen, which we thought would prevent a loved one from thinking a call like this would be necessary. Zach’s loved one did not know we were communicating with Tyler and was unfamiliar with how to initiate a garmin message. Ultimately because of our slower progress and the coming cold front, a call was put out in the last hours of the trip. This call emphasizes the importance of establishing expectations with loved ones at home about communication before heading out. We both truly regret that SAR was incorrectly called. Besides that unfortunate mistake (and although everything took longer than planned), the trip went quite well, particularly considering the challenges involved. We climbed an unclimbed ice route on a frigid lake from an inflatable raft without a single "close call". Research shows accidents are most likely to occur not when carefully pushing limits, but due to complacency. Feel free to think it's stupid or crazy, but just remember those are subjective concepts that we often manipulate to justify our own actions and condemn the actions of others. Regardless, if you're hankering for a little aquatic adventure (and maybe a little suffering too! lol) Lieutenant Dan’s Aquatic Death Ride will be out there waiting!1 point