JeffreyW

Members-

Posts

68 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

28

Everything posted by JeffreyW

-

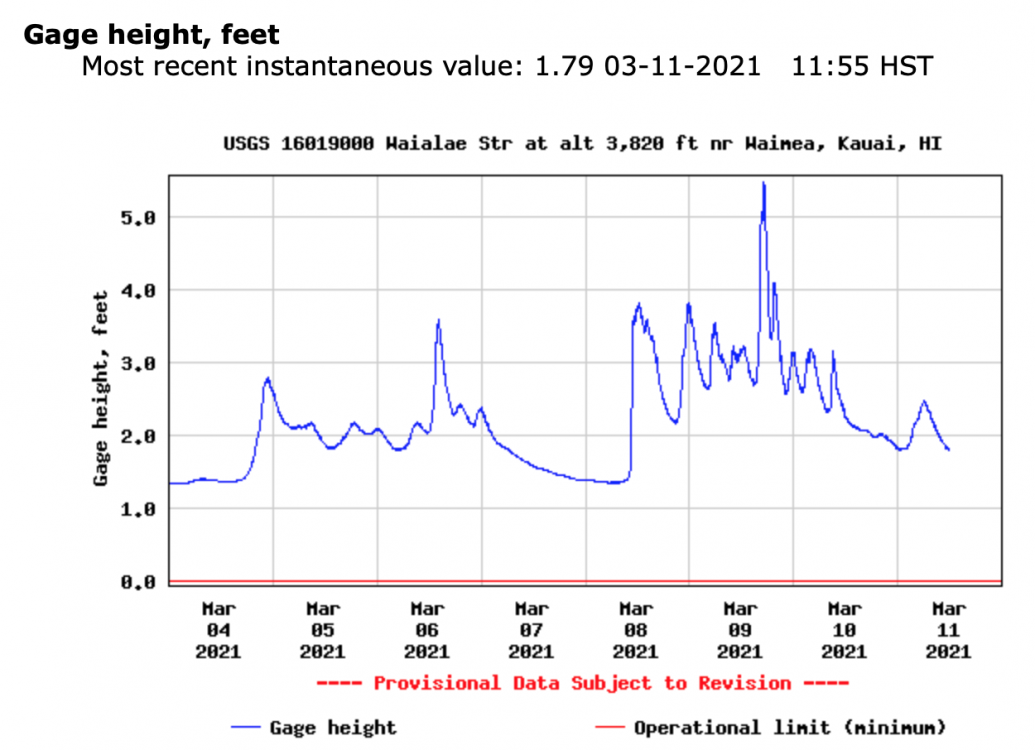

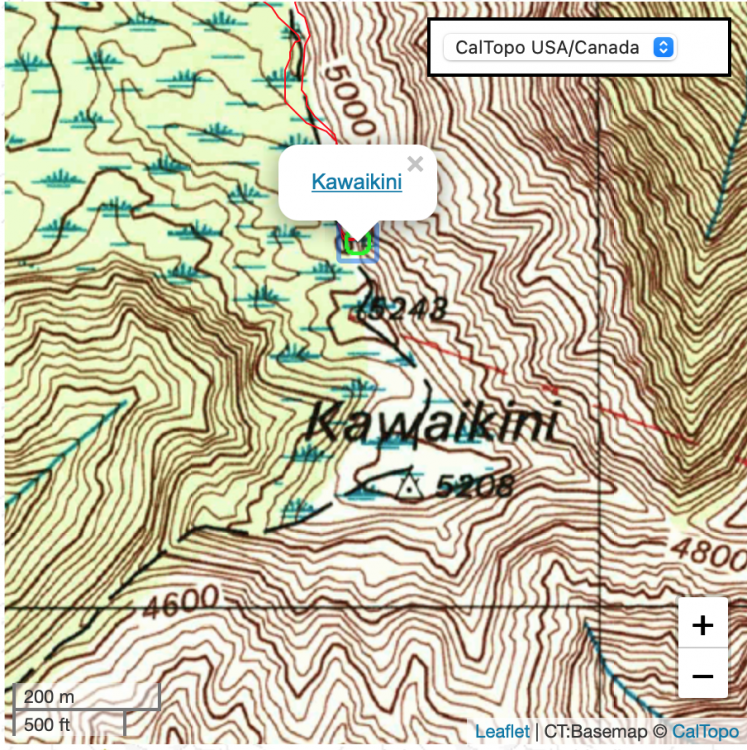

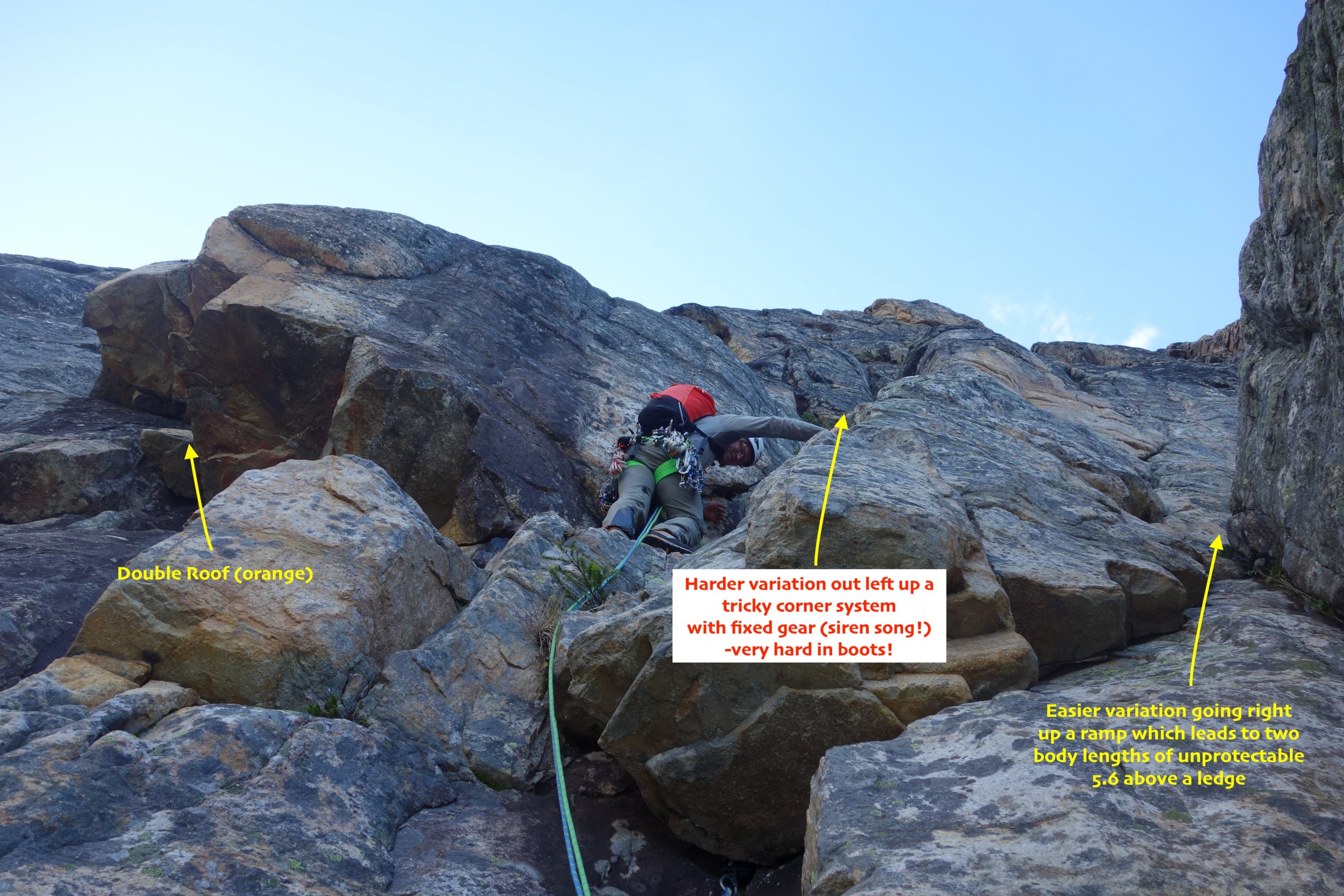

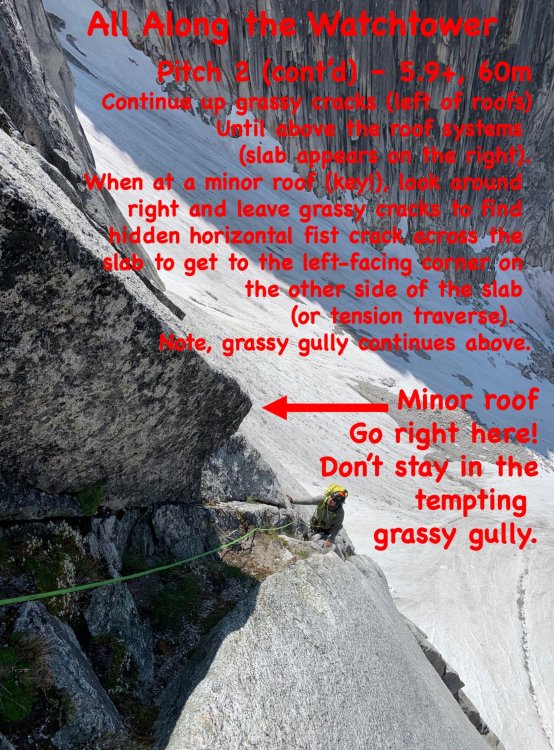

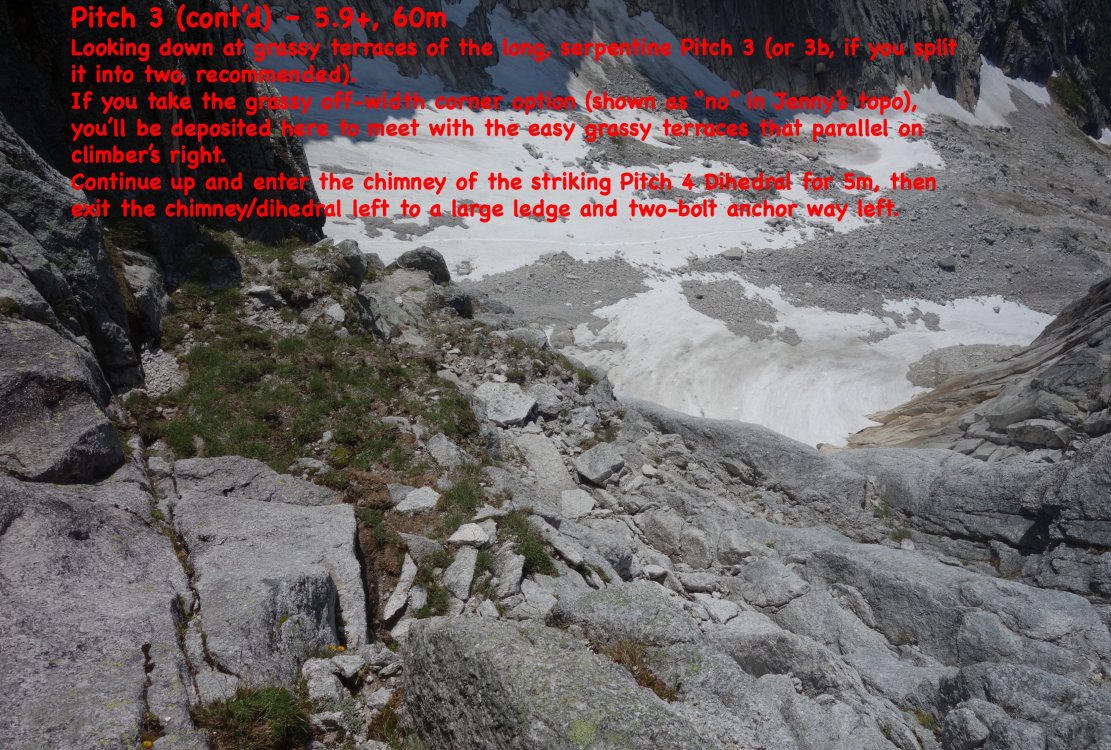

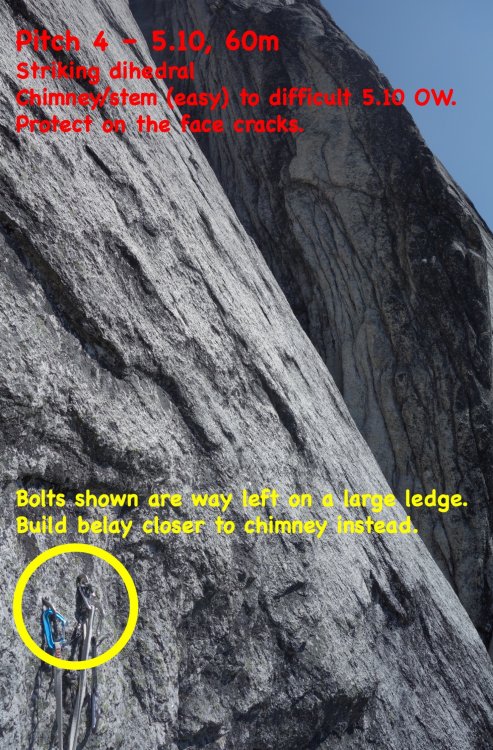

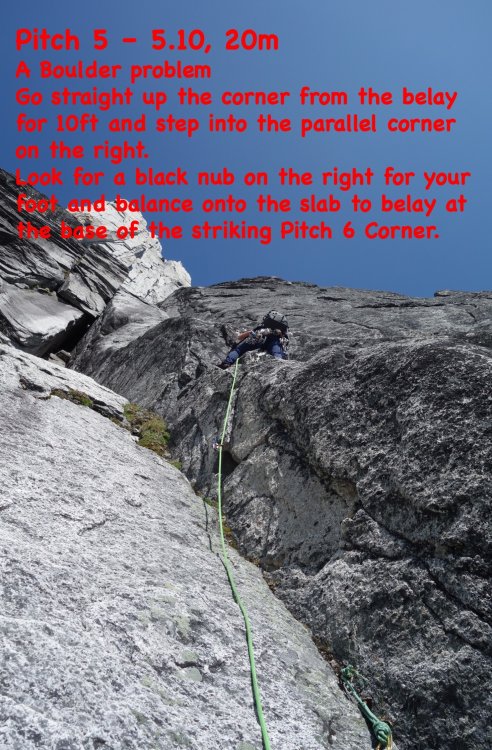

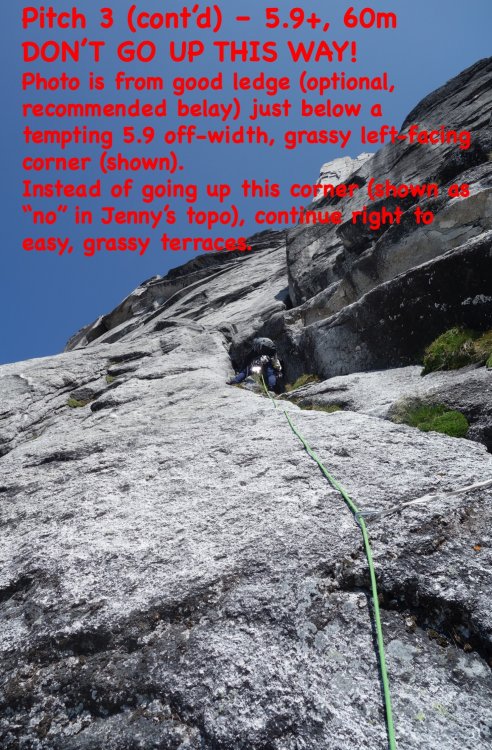

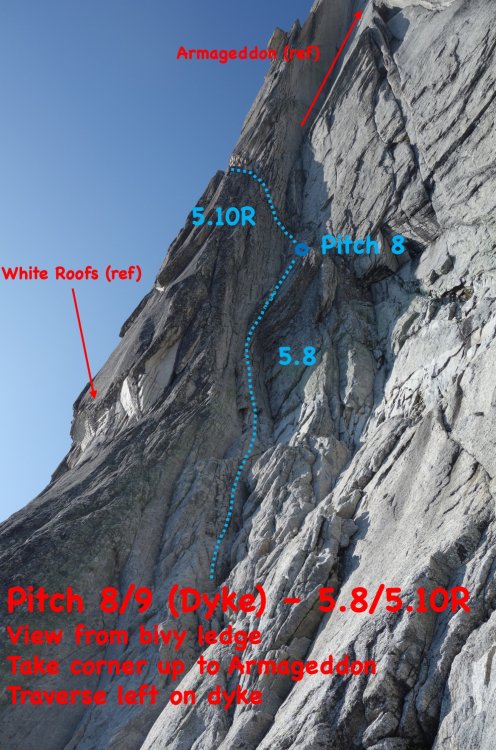

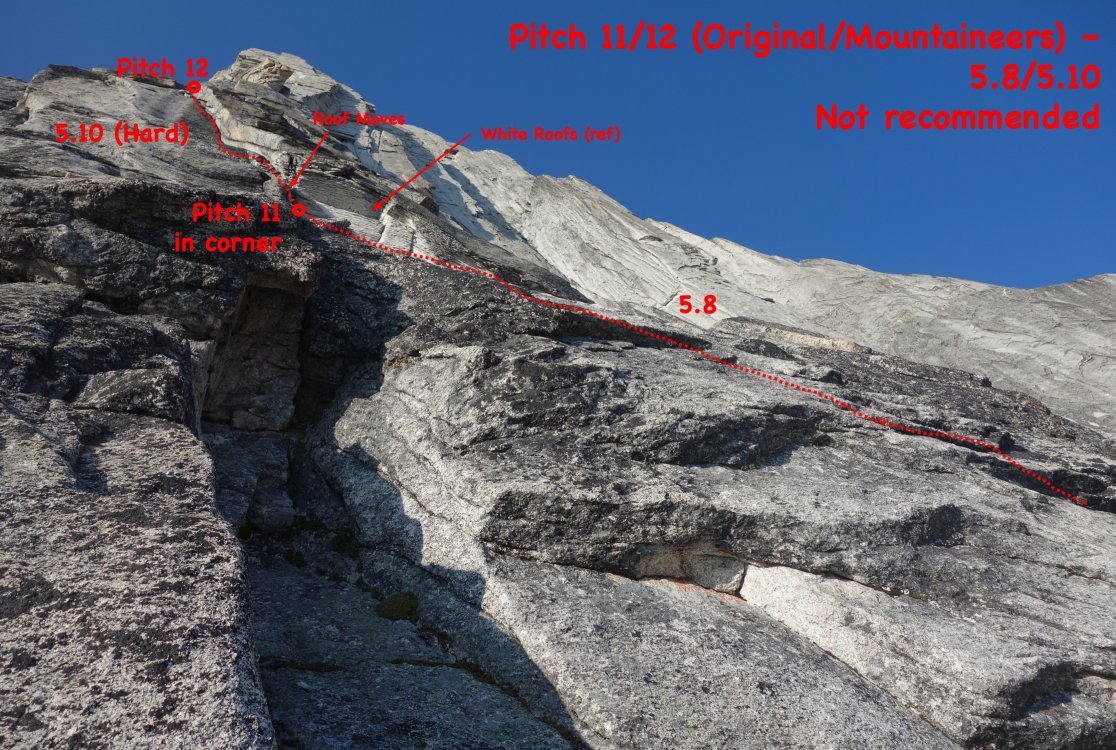

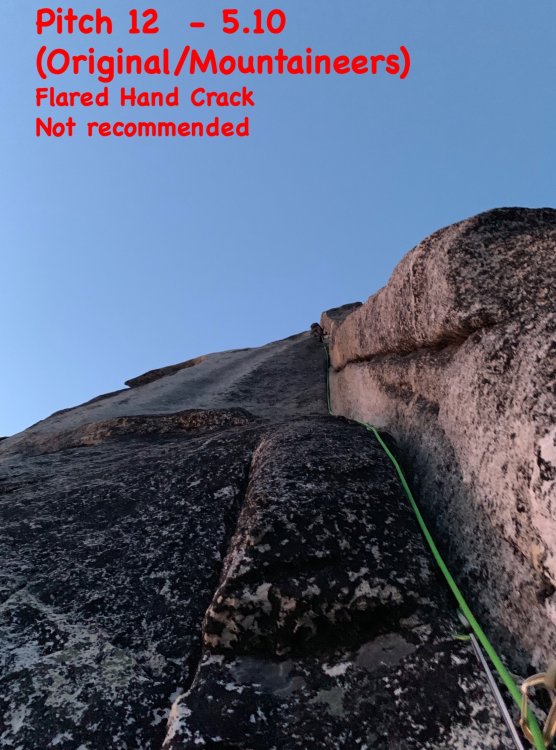

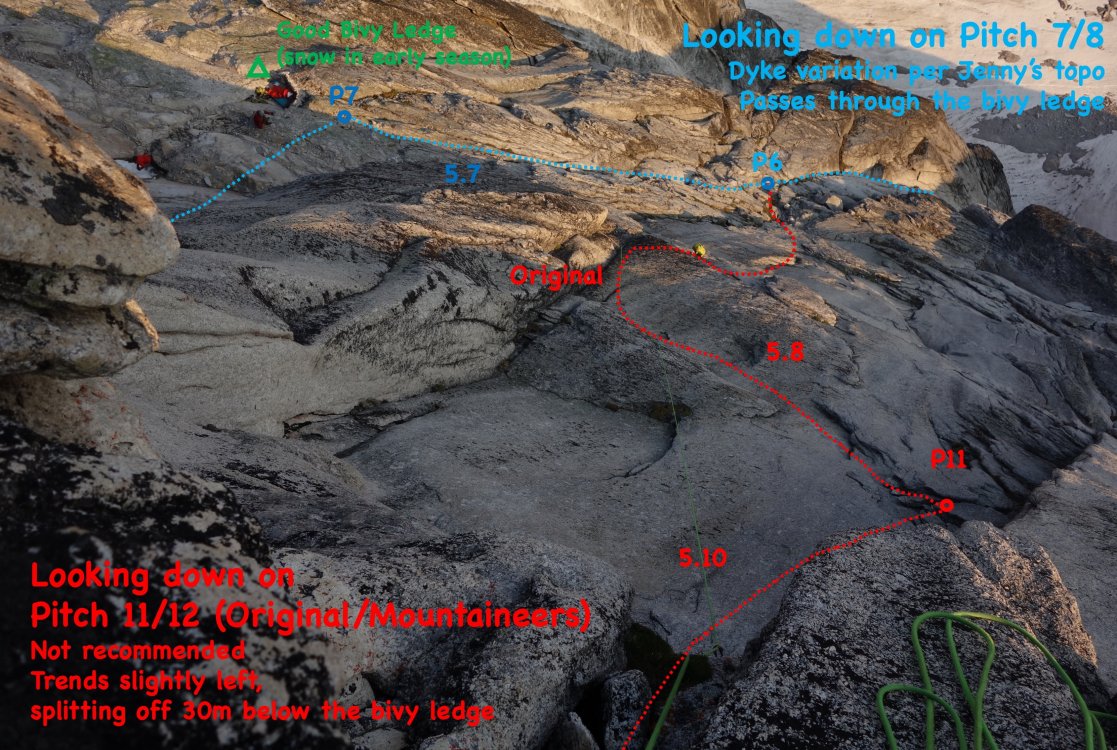

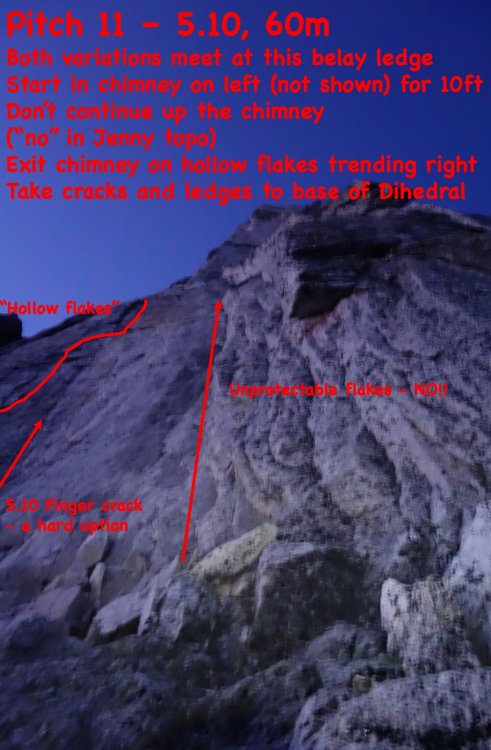

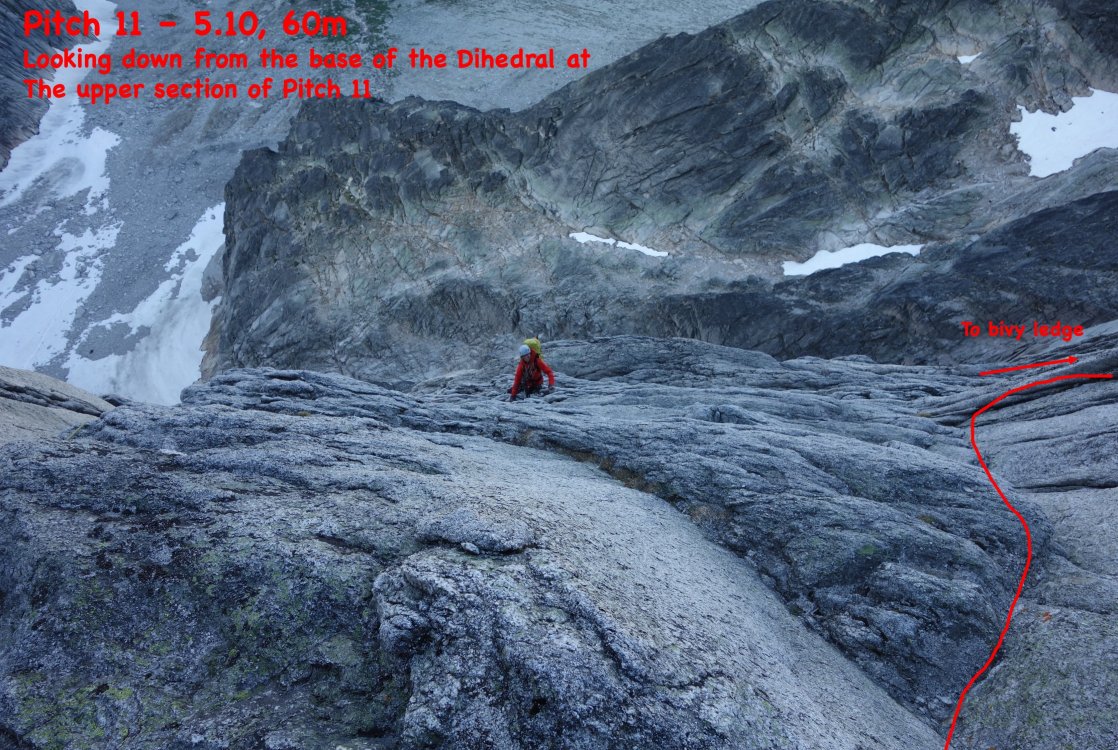

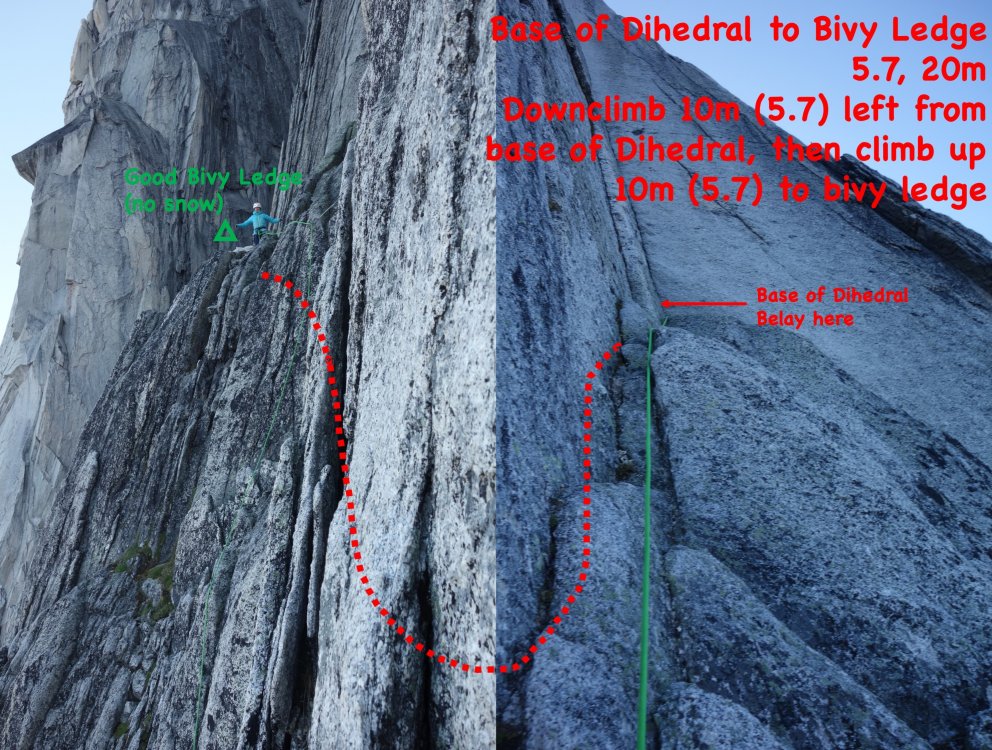

Trip: Sloan Peak - Fire on the Mountain (8 pitches, 5.10+) Trip Date: 10/07/2023 Trip Report: After attempting the SE Shelf on Sloan Peak (the "Matterhorn of the Cascades") in early-October with some Alpine climbing students and not summiting, Priti Wright and I (Jeff) went back the next weekend to climb Blake Herrington and Rad Robert's brilliant route Fire on the Mountain. I've honestly never alpine climbed in the Cascades this late in the season (typically rock climbing). Late season alpine can have really variable weather, but under the right conditions can be surprisingly perfect! One weekend, the mountain was a cold, snowy, winter wonderland. The next weekend, it was a beautiful, warm, dry, summer Type 1 outing. We studied all the past trip reports, downloaded all photos and route descriptions from every source, and still had a couple of issues. This report is not a one-stop shop of beta for this route since I still recommend you look at the past reports/pictures, but here are some extra learnings that we would've liked to have known going in. Read Wayne's report and all the reports linked (we had photos saved to our phone since routefinding was not obvious to us): https://waynewallace.wordpress.com/2018/08/02/fire-on-the-mountain-sloan-pk/ Also, save the excellent Mountain Project Description: https://www.mountainproject.com/route/122891276/fire-on-the-mountain Also, take a look at Steph Abegg's description and overlay of the SE Shelf route (which is the descent route): https://sites.google.com/stephabegg.com/washington/tripreports/sloan-bedal Approach I suppose, theoretically you could also approach via the Corkscrew Route (Sloan Peak Trail), then descend the SE Shelf to get to the base, then take the Corkscrew Route all the way back to the car, but I'm not sure how that compares to Bedal Creek. Most people seem to approach via Bedal Creek, so that is what I will describe. Bedal Creek starts by driving a few miles up a really nasty FS road (4096) which is not on Google Maps (high clearance 4WD advised...I know of at least one party that got a flat tire on this road, and I had to replace one tire after the trip). Here is the turnoff from the Mountain Loop Highway: https://maps.google.com?q=48.0856022,-121.3886677&hl=en-US&gl=us&entry=gps&lucs=,47071704&g_st=ic Take the road up until there is a small berm at the end (there is space for maybe 4-5 cars): https://maps.google.com?q=48.0719366,-121.3763550&hl=en-US&gl=us&entry=gps&lucs=,47071704&g_st=ic NW Forest Pass required (I think). No backcountry permit required. Gotcha #1: The road continues past the berm where you park, but do not start hiking up the road. The trail begins immediately uphill via a good, clear path and flagging from where you park. The USFS description is confusing when it says "Bedal creek trailhead is not located at the end of the road." (that's not a typo, but it is a poor description) There are many trip reports of unfortunate souls continuing up the road only to realize the trailhead was back where they left the car. The Bedal Creek approach (despite all previous accounts) was weirdly difficult to route-find. After many iterations, I think I finally nailed the approach if you are trying to get to the West Face, North Ridge, SW Face, or SE Shelf. Here is a CalTopo map with tracks, turn-by-turn waypoints and water sources (recommend downloading the topo map and satellite map for offline use with these tracks and waypoints): https://caltopo.com/m/RFMPB/LE9HFB06R0Q6PE6H 2-3hours to reach camp under the gigantic boulder in the Bedal Creek Basin (site of the old Harry Bedal Cabin who mined for asbestos in the early 20th century). This is a fantastic site with spring water nearby on flat grass that can fit multiple tents. The only downside to this site is that it is so comfortable and idyllic that you won't want to leave. It is also the site of Washington's most secure and gleeful V1 highball. Many folks climb Sloan in a long day from the City, but we did two nights out for a leisurely Type 1 camping trip (plus limited Fall daylight). Camp in the basin, or higher up at one of the sites on the South Ridge (very close to the start of Fire on the Mountain or the West Face route). See waypoints in CalTopo Map Gotcha #2: Most of the season you will encounter snow and running streams on approach for water sources. We didn't get any snow or water above camp until we descended to the glacier...oops. Carry water. Above: The West Face. Note that the "West Face route" (5.8) actually begins on the Southwest Face (which is on the other side of the right-hand skyline shoulder) Above (SW Face): Fire on the Mountain starts on the right hand side and goes straight up to the pointy gendarme. The West Face route (5.8) starts up the left-trending ramp on the left side of the face that you can see in the picture above. Pitch 1 (shown above) starts in a chimney then finger cracks (5.10+) then belays on a shelf above the obvious finger cracks. Pitches 1 and 2 take the longest, then the rest of the route is fast and cruiser. Money pitch! Pitch 2 (Gotch #3): the FA party did Pitch 2 in two pitches, but all parties since have done it in one long pitch. We ended up splitting up the pitch due to routefinding issues and rope drag, and it seemed logical to split this pitch up since it is so wander-y. Some reports showed climbing a wonderful hand crack flake above the belay, but NO! Ignore this beautiful crack (shown above), walk 10ft to the right on heather and find another beautiful hand crack next to an off-width. Climb the hand crack on the right, then traverse right to a small ledge. Climb up and gradually right on runout face to a "vertical seam"....we never found any of this since the face climbing was too scary so I backed off. Instead, we did a low, hand traverse to a grassy gully that led up to the roof (this was a complete garbage variation). I don't know...weird pitch...I never figured out where to go, and you can't see the roof from the bottom of the pitch...just keep trending up and right). The roof was super runout, save your #3 and 4 for this. I would have very much liked to have had a second #3 and one #4 for this pitch. Pitch 3 (shown above): climb the obvious, right-leaning crack, and don't be suckered straight up or left. Pitch 4 (Gotcha #4): This is NOT an Offwidth (unless it has changed in 10 years)! The Mountain Project and the Steph Abegg descriptions of this pitch are correct. It's just an obvious straight up, right-facing, dirty corner. Very straightforward. End on top of a pedestal (old piton rappel anchor from Kearney is down and left of the pedestal). No place for a #4 on this pitch (what the hell Blake!) Pitch 5 (shown above): Get your slipknot ready before you get off the deck and eye up the chickenhead (shown above)! Follow knobs then a ramp leftward. Skip the first right-facing dihedral and continue leftward to the second right-facing dihedral (5.10c). Belay just above the dihedral or keep going as much as you can in order to make Pitch 6 shorter. At least one party I know accidentally went straight up (into a right-facing dihedral) from this belay instead of starting off on the left; they found hard runout climbing to get back on route. Follow the chickenhead! Pitch 6: Climb as high as possible until you run out of rope (consider simul-climbing because it's no harder than 5.8). Skip the heather ledge and keep climbing into Pitch 7. Skip the unnecessary "boulder problem hand crack" and just take the path of least resistance out right then back left. Just chose your own adventure and continue straight up. It wasn't harder than 5.8 unless you just want to do a 5.10 boulder problem. Keep climbing, aiming for the pointy gendarme. Lots of good belay spots. Pitch 7 (shown above): If you extended pitch 6 past the shallow, heather ledge, chose your own adventure up the easiest path (no more than 5.8 if you chose wisely) and continue straight up to the pointy gendarme. DON'T start traversing too early! Continue aiming for the pointy gendarme summit until you reach an overhanging bulge (shown above) and you are forced to traverse out left. Belay under this overhanging bulge. You definitely want to split this pitch into 2 pitches, which is very logical because (1) rope drag is terrible on the traverse and (2) you can stretch this traverse pitch and end it above the heather ledge where you feel really comfortable to unrope. Note: for reference, there is a steep, slabby gully on the left side of the gendarme...don't go here! Stay on the prow and traverse high which puts you directly onto the final heather ledge. Once at the safe, heather ledge, you can unrope, put comfy shoes on (it's 3rd and easy 4th class from here), and coil the rope. Gotcha #5: Don't start traversing right at the first heather ledge system you see at the top because it does not join the Corkscrew Route here. Whether or not you are opting for the summit, traverse left on gentle heather for about 30m until you reach a gully. Ascend this gully for another 30m (3rd and easy 4th) until you reach the HIGHWAY that is the Corkscrew route (shown above). From here, leave your stuff and go left, following cairns, a nice path and some more 3rd/4th terrain to the summit (~30min to summit). Or, if you skip the summit, take the Corkscrew highway going right. Pictured above: descending the corkscrew trail traverses counter-clockwise around the Southwest side of the mountain where you will get a view of the impressive East Arm. The SE shelf descent route is a lower shelf beneath the East Arm. You will need to descend down slopes down an obvious gully to a rappel station (15m rappel or low-5th downclimb) which takes you to the top of the SE Shelf. Some parties rap off the shelf onto the glacier, but we found that just going all the way down the shelf was pretty fast and safer (plus the moat at the bottom of the rappel could prove tricky). There is some low-5th slab climbing at the bottom of the SE shelf. See some of my waypoint notes in my CalTopo. Enjoy! Gear Notes: Doubles to #2, single #3 (lots of finger size cams). Would have liked an additional #3 and also a #4, but not necessary. Didn't bring ice axe or crampons since we knew that the glacier could be avoided by climbing slabs in late season (recommend ice axe and aluminum crampons for added safety). Bring lots of water. Didn't have any water or snow from our bivy site in Bedal Creek all the way to the glacier on descent. One hiking pole each was really nice. One big follower pack. Approach Notes: Download this map (topo and satellite) plus the routes and waypoints: https://caltopo.com/m/RFMPB/LE9HFB06R0Q6PE6H

-

[TR] North Pickets - Mongo Ridge (Tower 1) 07/01/2022

JeffreyW replied to Jake Johnson's topic in North Cascades

Good effort, team!! Wish the pics were still available. I'd love for someone to figure out the optimal way to ascend Tower 1. I thought it was very cruxy/scary! -

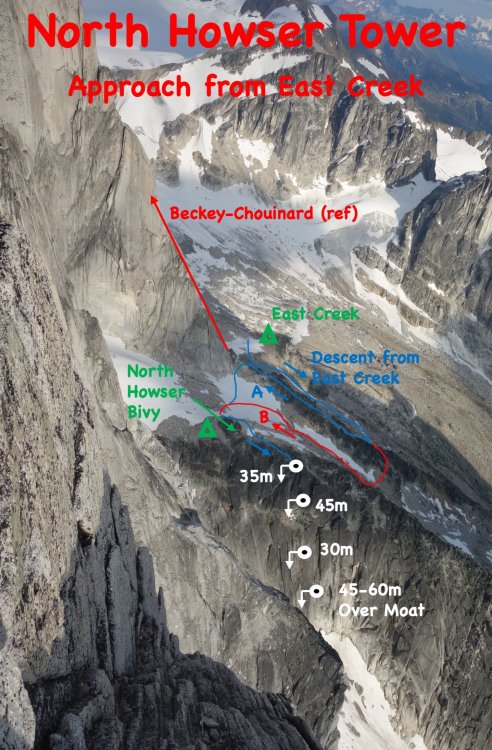

Trip: Mount Shuksan - Price Glacier and Nooksack Tower (attempt) Trip Date: 05/29/2023 Trip Report: Trip Dates: May 27 (Saturday) - May 29 (Monday), 2023 (3 days/ 2 nights total) Climbers: Jeff and Priti Wright Climb: Price Glacier (50 Classic) on Mount Suksan's North Face (successful) + Nooksack Tower (unsuccessful) along the way This report contains conditions on two routes: one is currently a sandbag and one is currently a featherbag...that way everybody has something to comment about! Descent Options: Fisher Chimneys, but there is snow on the trail all the way up Lake Ann according to the rangers on May 27. Rangers recommended floatation on the trail. White Salmon Glacier (skis), but you have a heinous bushwhack on the way out per this TR (link) "Once at the bottom of the glacier, we initiated the most miserable slide alder/thorny bush battle of my life. I was in a tee shirt, and was absolutely brutalized trying to fight through the vegetation with skis on packs." Sulphide Glacier (this requires a long car shuttle) but probably the easiest/fastest way off the mountain. Lots of traffic on Sulphide, no evidence of folks coming up White Salmon or Fisher Chimneys Memorial Day weekend. The snow on the Lake Ann Trail is perhaps scaring people away from Fisher Chimneys. Hanging Glacier Route No matter what you chose, make sure to have GPX tracks of all descent routes downloaded to your phone. You can find GPX tracks at caltopo.com or peakbagger.com. Logistics: Cache a bike or car at White Salmon Base (White Salmon Glacier or Hanging Glacier descent) or Bagley Lakes TH (Fisher Chimneys descent). We locked a single bike to a signpost behind a guardrail (very discreetly) near the White Salmon Base Area. It's a short/fun bike ride downhill and on the dirt road back to Nooksack Cirque Trailhead to your car. Note: White Salmon Base parking lot is closed for construction and no parking is allowed there. Therefore, I'd probably recommend Fisher Chimneys descent with a bike cache at Bagley Lakes parking lot. The road to Artist Point is partially open, so you can cache a bike higher up the road, maybe. You can also hitchhike down Mt Baker Highway then walk the extra 2.2 miles from the NF-32 turnoff to the Nooksack Cirque Trailhead. Park at Nooksack Cirque Trailhead and start from here. To get here, take NF-32 off of Mount Baker Highway, then branch off right onto NF-34 to the end of the road. NF-32 and NF-34 are dry, dirt roads in good condition currently. Plan for extra days out. The Price Glacier route can be trivial or it can be really complex and time consuming. Sandbag: In its current condition, there was no really technical terrain on Price Glacier (this will change day-to-day!). Just easy snow walking all the way up....much easier than the North Ridge of Baker. The bergshrund has a trivial crossing up the middle that might last a few more weeks. If it's out, however, then you're in for some mixed climbing out of the moat on the left or right side of the shrund. Featherbag: Nooksack Tower has a lot of rockfall, the worst rock quality I've ever experienced (even after the Southern Pickets Traverse!), VERY sparse protection, lots of required downclimbing, and difficult routefinding. Basically, YGD, and I don't recommend this peak at all to anyone, probably ever. I know it's a Cascade classic, but I was so shut down on it and also so unimpressed. It's just terrible...and too dangerous imo. All you successful Nutsackateers are free to comment about how trivial it is and how I need to harden up. Approach We got to the Ranger's office in Glacier at a leisurely 9:30 (they open at 8:00) but recommend you get there as soon as they open because stashing the shuttle/bike takes time. You might also want to consider getting your permit a day early, then sleeping at the trailhead to get an alpine start. Then we discreetly locked up a bike off the road near the White Salmon Base area and drove to the Nooksack Cirque TH. At the trailhead, head straight to the river and slightly downstream to reach an improved log crossing to start the Nooksack Cirque Trail. The trail has a few downed trees, but is generally in good shape. First improved log Crossing just at Trailhead Second improved log crossing along the trail...Priti doing her sexiest logwalk pose After reading this legendary trip report (link) from Pellucidwombat about their 9/2/22 Labor Day Weekend climb, we came prepared to encounter anything. This report is definitely worth a read. Mad props to those two for getting it done in those difficult conditions. I really feel like earlier in the season, the better for this climb. The original log crossing across the North Fork Nooksack River (now gone) has been there for years and years and provided access leaving the Nooksack Cirque Trail into the Price Lake valley. Pellucidwombat describes how they found a new crossing and provided us with the GPX point. Their new crossing is also gone (not underwater, but actually swept away). The best place to ford the river that we could find is at the original log crossing location (N 48.87097° W 121.61267°). We went up and down the river for hours to look for a new crossing. This location spot is the least sketchy spot to cross. A few parties have done it unroped this season (with skis!), however I thought it was sketchy and high enough to cross on belay then set up a tyrolean for the packs. Our tyrolean steps: Set up one end of the 60m rope to the tree as a retrievable bowline (equivocation hitch could also work, but this thing give me the heebie-jeebies, and it might be harder to release after a tensioned tyrolean). Practice this at home first! Tie-off of the bowline tail as as a Backup/Failsafe. Cross the river on belay with a bight of rope attached to your harness. Note: bring a bight across, not just the other end. Keep both ends of the rope at the start. Once across, make an anchor around a tree (2x 120cm runners work), then bring the anchored end of the rope tight and tension it with a simple Z-pulley (I used two micro traxions since they release easily). The taut, Tyrolean line goes from the Bowline to the Z-pulley. If you happen to have a GriGri, it is much safer to use the GriGri as a progress capture pulley than the micro traxion (link). Technically, Petzl says YGD if you use a micro traxion as a progress capture pulley for a tyrolean (link). Of course, a regular/passive pulley (such as a locked-open micro traxion) with an old-school progress capture hitch (Bachmann, prusik, Valdotain, etc) also works well and is safer. The free end of the rope going back to the start gets pulled in and attach a backpack to a figure-8 on a bight. Clip the pack onto the tensioned line and pull the pack across with the slack line. With a 60m rope, the person at the start should hang on to the free end of the rope to pull the carabiner back across. Therefore, you have a tensioned line and a slack line (tether). Re-tension the Z-pulley between each crossing. Once both packs are across, follower confirms that the Removable Bowline is set up, removes the Backup, then Tyroleans across the tensioned line (nothing fancy, just hand over hand with a locker on their belay loop) Release the tension on the Z-pulley. The Bowline (or EQ Hitch) won't release while the line is tensioned. To release the micro traxion (or GriGri or progress capture hitch), you'll need to tighten the Z-pulley slightly in order to open the toothed cam (practice this if you don't know what I'm talking about). Pull the pull side of the rope to release the Bowline (or EQ hitch). Note: this may be a *vigorous* pull! If you've set up an EQ Hitch, practice ahead of time what it feels like to pull on each line alternating between each bight release. Releasable Bowline (pictured) from 'Down' by Andy Kirkpatrick: the most effective ghosting technique, due to the fact most climbers know how to tie a Bowline, it’s safe if carried out correctly, and it works. In this set-up, a 120 cm sling is being used. You can use a longer sling (240 cm) or cord, but 120 cm is the minimum length. Anything shorter and the Bowline will probably not fully release. Also note that the tail of the Bowline must be long enough to tie an effective and secure the Bowline (30 cm long), but not so long that the tail does not fully clear the Bowlines when the RELEASE rope is pulled. There is flagging at either end of this river crossing location. From here, follow frequent flagging up the slope through mild bushwacking and bootpack trail until it opens up and you get your first glimpse of Price Lake. If you lose the flagging, retrace your steps and try to get back on course (GPX tracks are helpful). This section of the approach would be much harder without the flagging, so please try to preserve it. This section from the North Fork Nooksack River up the slopes to the Price Glacier moraine is fairly trivial, but it is STEEP! Once the slope opens up, you first traverse across talus and boulders to eventually gain a lateral moraine. Follow the moraine bootpack trail (green line pictured below) until you are under a cliff band. Immediately gain the cliff by the first gully (red line pictured below), then follow the undulating ridge (many bivy sites here) until you are forced to go down onto the open snow slopes. We bivied on top of this ridgeline the first night, but a strong party can easily make it to the Nooksack bivy which is recommended so that you get on Price Glacier early the next day. Priti and I originally planned to spend one day on approach, one day on route (Price Glacier only), then fly off the summit the morning of the third day. There was a team of 2 who were one day ahead of us (Eli Philips @eeelip and Ian Mock @cascade.ian) who impressively planned to do Price Glacier with skis on their backs and also tag Nooksack Tower along the way. When we got to the Nooksack bivy, and saw their tracks going up the Nooksack Tower approach gully (and after watching them effortlessly float up the Price Glacier in just a few hours), we couldn't let these guys 1-up us! So, we changed the plans and spent all of our second day questing up Nooksack Tower with just the pictures of the pages from Selected Climbs. The route line in the book is a little deceiving since it goes straight up the "central couloir" which looks to have overhanging terrain, and not the 4th-and-low-5th class terrain advertised. If we had done some research ahead of time, these two trip reports would have been handy from 2013 Jason G (link) and 2014 Dave Shultz (link). Eli and Ian (as we found out later) also didn't have enough beta, starting too low in the approach gully and bailing after getting spooked on runout terrain. I think we started at the right spot which is to go as high in the approach gully as possible then start up the right side at some TAT (don't get suckered up the chimney directly up the middle). The route has 3 distinct sections: low angle ramp/slabs (red line below), low angle couloir (orange line below), then a sharp traverse out left to more low-angle ground to the summit (green line below: the presumed route which we did not explore, so do not trust this green-line-overlay!). The start of the route has a few body lengths of wet, low-5th ledges with good gear in a corner which soon eases to low 4th class and little protection. Pass a large rappel anchor at the top of the slope where the angle steepens, then make a short traverse out right under the steepening wall and turn the corner to continue up and left into a wide gully (orange). Continue up this gully which gradually steepens to gain the ridgeline and a prominent notch where you get amazing views of Price Glacier. Side Note: A neat option for future parties might be to bring all your kit up to this ridgeline (top of orange line), cache your packs, summit Nooksack, retrieve your packs, then make two 30m rappels down the other side of the ridge to the top of Price Glacier which would bypass much of the heinous descent and shorten your total trip. The only downside is that you'll bypass the fun lower 2/3 of the Price Glacier route. From the ridge, we accidentally continued out right onto the West Face (yellow line). The route got difficult, loose, with bad protection (spooky!), so we tucked our tails and bailed. A key bit of beta from JasonG's TR would have helped us tremendously: "For aspiring Nooksack Tower ascensionists ... traverse hard left [at the ridgeline] across 3 or so ribs as soon as feasible once you've climbed up and right from the snow gully. Then, basically traverse left until you get to 3rd/4th class gully that will take you to the summit. This is key, don't be pulled up and right by the numerous rap stations-these led to the North face . Alpine Select gives this variation a 5.7/.8 rating and it felt quite spicy in boots." Note: I presume this North Face route continues straight up from the orange line. Photo above is taken from pelluciwombat 9/2/22 TR and not representative of current conditions. Nooksack Tower Descent: Selected Climbs warns that the descent off Nooksack Tower takes longer than the ascent, which is true! We only had one 60m rope so we made a couple short rappels with a lot of belayed downclimbing between stations. Two ropes would definitely had been nice! Be prepared to freshen up lots of anchors with new tat and maybe some leaver nuts since a lot of the anchors are snafflehound-tattered stuff from JasonG's 2013 ascent. Priti nearing the prominent notch at the ridgeline. We went right (West Face). North Face is pictured in the center (possibly). Likely, the Beckey route is way left around the other side of the skyline ridge. We bivied our second night after our 12hr attempt on Nooksack Tower at the Nooksack Bivouac (the prominent saddle under Nooksack Tower). Right now it is flat and snow-covered for several tents comfortably. Note that late in the season (according to pellucidwombat), this saddle is just a knife-edge snow ridge and not conducive as a bivy site. There is another nice bivy site on flat snow on an obvious rocky outcropping on route just after traversing out from the Nooksack Bivy. With fresh steps to follow, the Price Glacier itself was a non-event, taking 3-4 hours to ascend the face. Pure Type 1 Fun! We may be the first people in history to have steps kicked and the proper route found for them on Price Glacier! Luxury. No gear was placed, no crevasses were fallen into, and we got the muscular endurance workout we were hoping for. We each carried one picket and the follower carried one screw in case of a crevasse fall. The bergshrund crossing was easy, located in the middle (pictured below). I would almost feel comfortable solo'ing the Price Glacier in its current conditions (from a technical standpoint) except for the fact that it is still a glacier with several potentially dangerous crevasses, so a rope and glacier travel gear is still recommended at the very least. Above picture: Priti crossing the bergshrund in trivial conditions. This is traditionally the crux of the route. If there is no way to cross it directly, then mixed ground must be taken across the moat on the right or (more commonly) left side. Once on top of the face, it is necessary to make a wide circumnavigation to join the procession of Sulphide climbers. Instead of the wide circumnavigation, we followed Ian and Eli's clever shortcut, traversing high under the summit pyramid, then ascending to a notch in the South Ridge then descending slightly to join the main route to the summit. The summit pyramid is in easy conditions now, with snow most of the way to the top, with just a short section of 4th class rock (a few body lengths), reaching the summit at noon after starting out at 6:00AM. The descent went smoothly, then Priti grabbed her stashed bike and picked up the car, for a multi-sport weekend! Thanks North Cascades! Gear Notes: Single rack to #1 (used on Nooksack, didn't place any rock gear on Price...still a good idea to bring some rock gear for Price just in case, small cams are nice on Nooksack) 2 pickets for glacier travel (one on each person at all times, more pickets if you're not comfortable soloing "steep" snow) 1 knifeblade (didn't use) 10 ice screws (didn't place any, good to bring maybe 4-5 at all times) 12 runners (used a few to make anchors on Nooksack Tower, bring LOTS of anchor material and nuts if you plan to climb Nooksack) small rack of nuts (great anchor gear on Nooksack Tower) V-threader Rappel device for Fisher Chimneys rappels (good to have for emergency anyway) we did not bring rock shoes but I might have liked them on Nooksack (although traditionally it's been climbed in boots, but I'm not hard enough) crevasse rescue kit single hiking pole each (very nice for all the snow walking) 2 alpine ice tools each (Petzl Gully would be perfect) tent was very nice to have on exposed bivy spots (as opposed to open bivy or tarp) Floatation (snowshoes? ugh) *might* be nice for Lake Ann Trail, but I think skis are maybe a bit contrived for these current conditions considering how much bushwacking you do on approach and descent. We didn't bring any floatation and were very glad we didn't. 1x 60m rope (a pull cord or half/twin ropes would have been nice for Nooksack Tower) Approach Notes: Nooksack Cirque Trail

-

[TR] Mt Shuksan - Price Glacier 09/02/2022

JeffreyW replied to PellucidWombat's topic in North Cascades

Amazing trip report! Thanks for putting this together. FYI to everyone, the new log crossing described in this report is swept away. The best place to ford the river that we could find is at the original log crossing location (N 48.87097° W 121.61267°). We went up and down the river for hours to look for a new crossing. This location spot is the least sketchy spot to cross. Some folks have done it unroped this season (with skis!), however I thought it was sketchy and high enough to cross on belay then set up a tyrolean for the packs.- 8 replies

-

- mt shuksan

- shuksan

-

(and 5 more)

Tagged with:

-

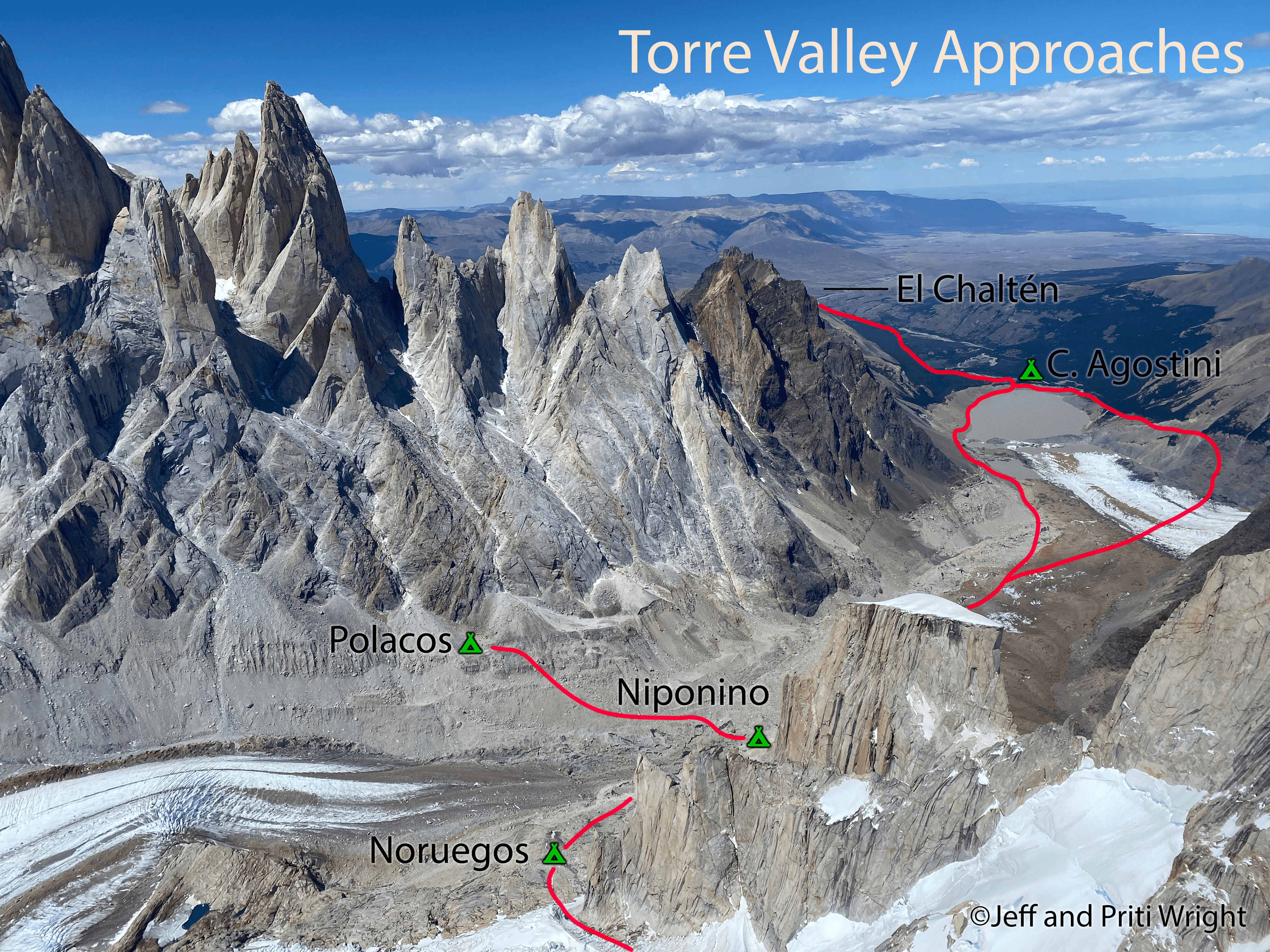

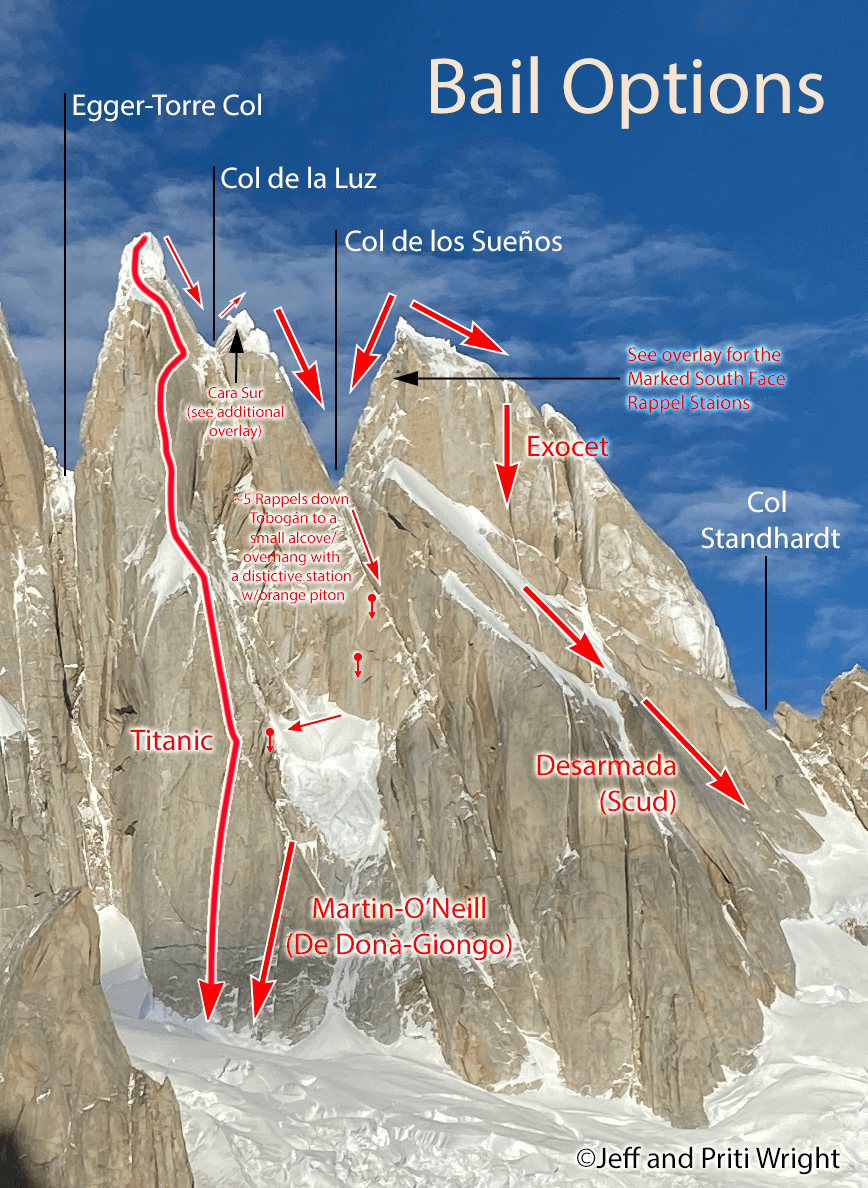

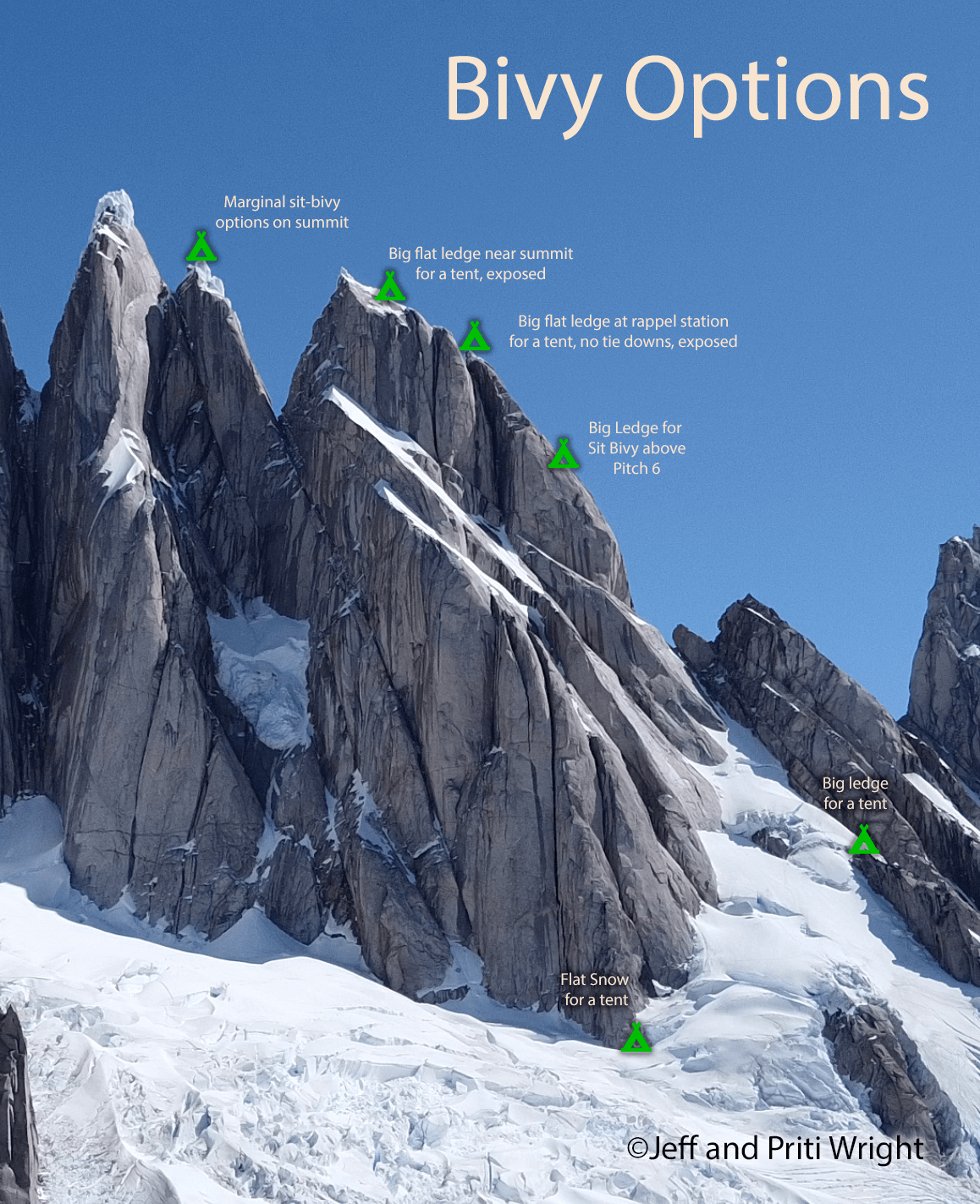

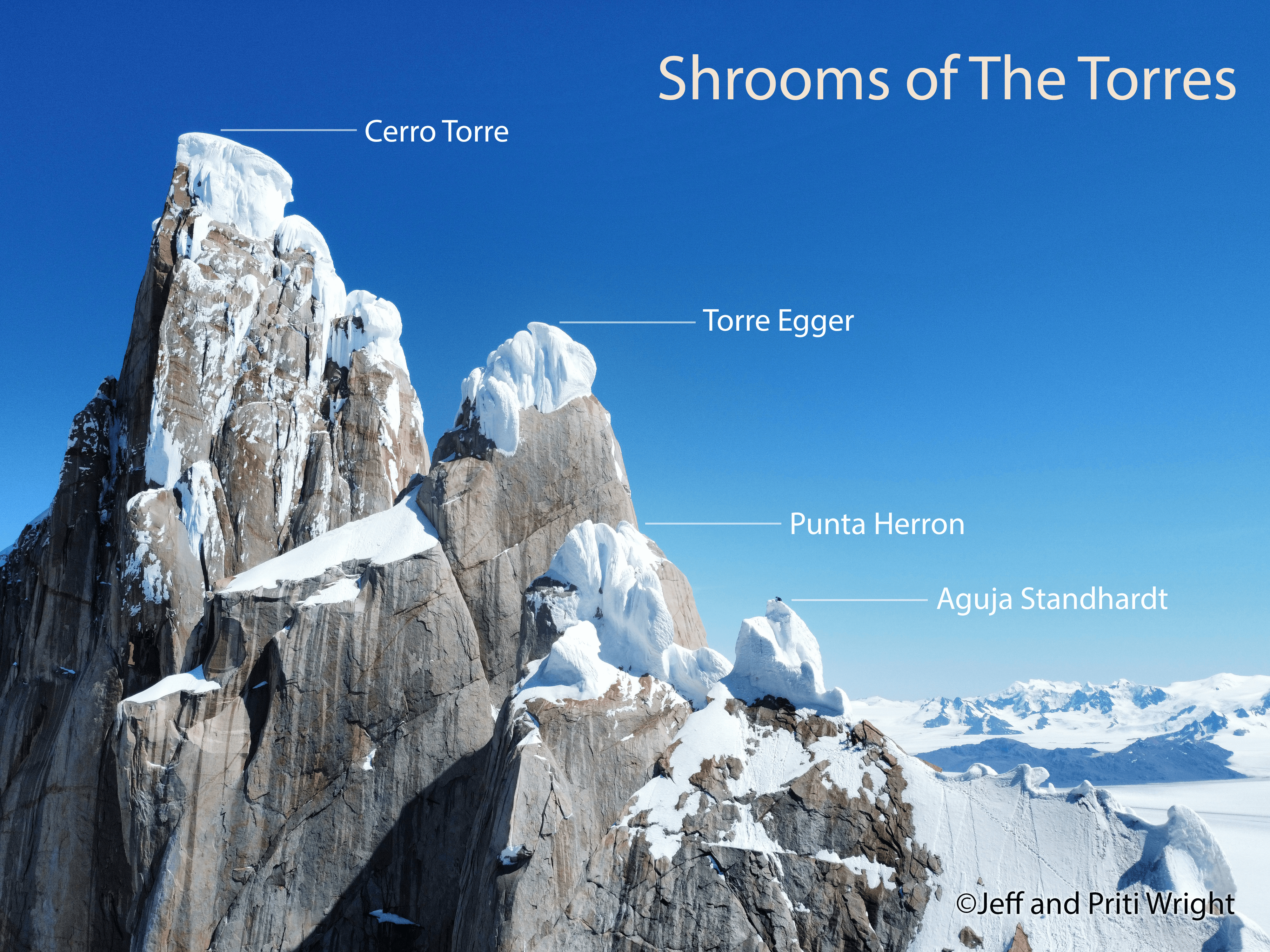

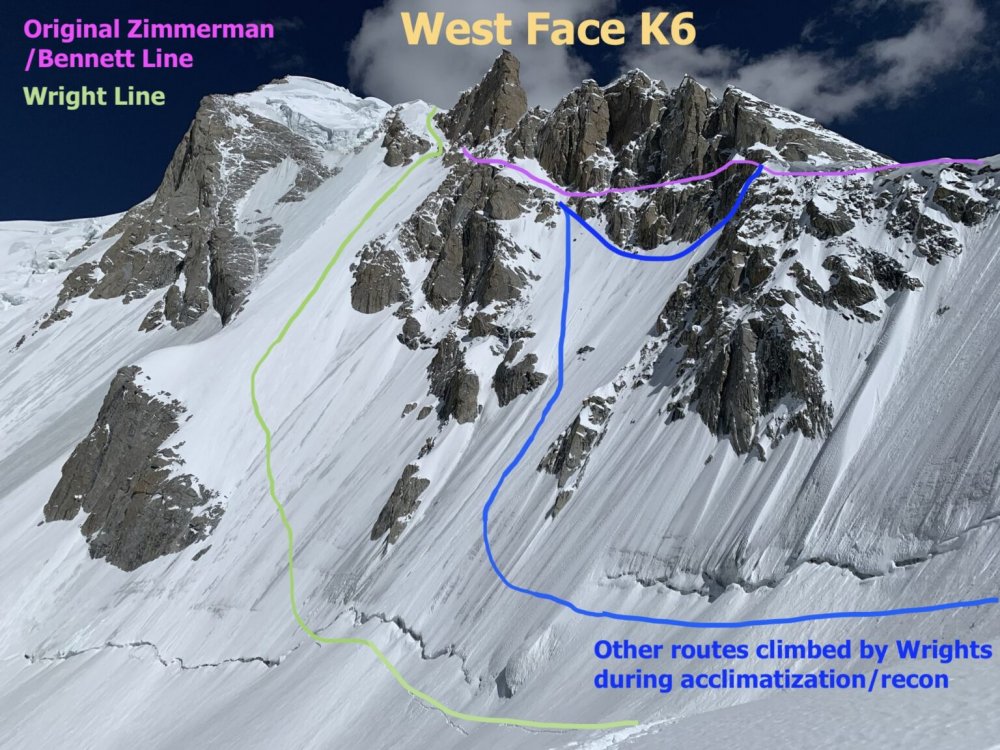

Trip: Patagonia - Torre Egger Smash 'n Grab - Huber-Schnarf Trip Date: 01/21/2022 Trip Report: Climbers: Jeff and Priti Wright Location: Patagonia - Chaltén Massif - El Chaltén, Argentina Traverse of 3 peaks: Aguja Standhardt - Punta Herron - Torre Egger Climb Date: January 18, 2022 - January 21, 2022 Full Trip Report: https://alpinevagabonds.com/torre-egger-traverse-a-smash-n-grab-story/ Climbs/Rappels Aguja Standhardt Climb via the North Ridge route Festerville (400m 90° 6c) in 15 pitches (14 pitches of rock and 1 pitch of rime ice) from Col Standhardt Aguja Stanhardt Rappel via South Face (7 Rappels) Punta Herron Climb via North Face route Spigolo dei Bimbi (350m 90° 6b) in 9 pitches (5 pitches of rock and 4 pitches of snow+ice+rime ice) Punta Herron Rappel via South Face (1 Rappel) Torre Egger Climb via North Face route Espejo del Viento (200m 80° 6a+, often referred to as the “Huber-Schnarf” route) in 5 pitches (3 pitches of rock and 2 pitches of snow+rime ice) Torre Egger Rappel via Titanic (countless Rappels, two downclimbing snowfields, and one 30m downclimb from the summit) In January of 2022, we completed another Patagonian “Smash ‘n Grab”, summiting three of the four peaks in the Torre Range via previously established routes (11 days Seattle-to-Seattle): Aguja Standhardt, Punta Herron, and Torre Egger. Including our ascent of Cerro Torre in 2020, we have now climbed all four summits of the Cerro Torre skyline, making Priti the first female to summit all four peaks. 2022 marked our fifth climbing trip to El Chaltén. In 2019, we completed a 10 day Smash ‘n Grab of Cerro Chaltén (Fitz Roy). In 2020, we spent two months in El Chaltén, during which time we climbed Cerro Torre on the route Via dei Ragni. Urgency and several parties in line behind compelled us to accept a top-rope on the final pitch of the summit mushroom of Cerro Torre, joining the conga line. Pink: The accidental line we took on wet, grimey terrain....oops (not recommended); Blue: the original route Festerville on golden granite Their 2022 traverse from Aguja Standhardt to Torre Egger enchained three distinct climbing routes (all established by different parties), climbing for four days and three nights, bivying twice on Standhardt and climbing through the third night up-and-over Torre Egger. After arriving in El Chaltén, we cached a tent at the standard Niponino Base Camp, carrying a tarp and a double sleeping bag for the traverse. We started on the route Festerville (400m 90° 6c) which follows the spine of the North Ridge of Aguja Standhardt for approximately 13 rock pitches. Another team of two (Michał Czech from Poland and Agustín de la Cerda from Chile) started up the route ahead of us and the four effectively joined forces, climbing symbiotically, each team helping the other along the way. After summiting Cerro Standhardt via 30 meters of 90° ice and rime, Michał and Agustín rappelled the Exocet route back to Base Camp while we (Jeff and Priti) made seven rappels down the South Face of Cerro Standhardt, continuing the traverse. The South Face rappels end 30 meters below the Col de los Sueños (the col between Standhardt and Punta Herron), requiring climbing the final 30m of the route Tobogán to reach the col. The traverse continued up to Punta Herron via the route Spigolo dei Bimbi (350m 90° 6b) climbing 5 pitches of rock and another two pitches of beautiful, vertical ice and rime to the summit. A single rappel from the summit of Punta Herron led down to Col de la Luz under the North Face of Torre Egger. Spigolo dei Bimbi included some of the most fantastic rock climbing that we have ever climbed in Patagonia! From Col de la Luz, we continued up the route Espejo del Viento (200m 80° 6a+, often referred to as the “Huber-Schnarf” route) in the dark of night for three rock pitches which ends in a long, run-out, wet, technical slab traverse under Torre Egger’s overhanging summit mushroom. We continued through the night, climbing two more moderate pitches up the mushroom on easier 70 degree snow and ice to the summit of Torre Egger at 2:00AM, the most difficult summit in the Chaltén massif. We continued through the night without a bivouac, descending 27 rappels and down-climbing along the route Titanic which follows the East Pillar of Torre Egger. Upon reaching the tent at Niponino in the Torre Valley after 44 hours of constant movement, we collapsed in the tent realizing we were too late to catch their planned flight home. Unfortunately, we neglected to notify anyone that we were missing our early-morning airport taxi. When the taxi arrived at our hostel Aylen-Aike, the driver woke up Korra Pesce who was sleeping in the room where we had previously slept. Korra notified the hostel owner Seba and Rolando “Rolo” Garibotti who were all quite worried and proceeded to notify rescue teams. Later that morning, Rolo successfully contacted us on our inReach before any rescue efforts began, teaching us a valuable lesson: let people know if you're going to be late! A week later, a team of bold volunteers attempted an unsuccessful rescue of Korra Pesce, the legendary French-Italian Alpinist, on the North Face of Cerro Torre who will be sorely missed by his friends, family, companions, and fans. Being back at home in the US by the time the accident occurred, we wished that we had been present to aid the operations. The 2021/2022 Patagonia season was marked by several notable deaths and rescues in the mountains as well as several celebrated new climbs. Patagonia continually demands of its visitors the humility that this place deserves. We really want to thank Rolando Garibotti and Colin Haley for their beta, support, and encouragement; Agustín and Michał for being a great team to partner with as we shared the same objective on Cerro Standhardt; Aylen-Aike for putting us up at the last minute in El Chaltén; Hector Tito Soto Nieto and Andrew Reed for loaning us your cams (we decided what route to do while on the airplane); our bosses and work colleagues for letting us go for a week with hardly any notice; Ilia Slobodov for the awesome weather updates while on route; and Kelly Cordes for the rad Patagonia gear. Priti on the summit of Torre Egger, 2:00AM. Time to rappel. Gear Notes: 2x Camalots to #1, 2x TCUs, 1x Camalots to #3, 6 ice-screws, a set of stoppers, and deadman stuff sack (substitute a jacket instead?) to rappel off of Torre Egger (or a retrievable ice tool anchor or downclimb) Approach Notes: Approach as for Col Standhardt

-

I am an experience climber who has climbed Triple Couloirs three times on three different years in various conditions. I consider myself a very conservative climber with a low risk tolerance who has climbed some of the most technical routes all over the world. I have only solo'd two "technical" routes in my life: one 5.6 rock climb in Leavenworth and Triple Couloirs, but I generally always prefer a running belay on all "technical" climbs. My personal opinion is that Triple Couloirs for the experienced climber lends itself to solo'ing. In the best conditions, TC has two very short ice pitches (less than three body lengths each) separated by three couloirs of snow which generally would be good terrain to self-arrest a fall. If you get to the first ice pitch and it is dry or thin, you can easily walk back down. If you get to the second ice pitch and it is dry or thin, you can easily walk back (reversing the moves or rappelling the first ice pitch). You can basically climb up and turn around when you get to a section that you decide that you can't reverse the pitch in its conditions. Yes, the route can be dry and it can be thin, but you can always turn around if it's not in great conditions. A fall from one of the two ice pitches would be relatively easy to arrest a fall. I teach students on arresting a fall on snow. I would classify the angle of snow in these couloirs relatively moderate self-arrest terrain (not the easiest, but not a difficult place to stop a fall). As a very experienced Mountaineer, I assume Dr. Thurmer was an expert at self-arrest technique on snow. I solo'd TC with three other friends at the same time, all soloing, carrying a 30m skinny rope to rappel or for emergencies or for a belay if somebody wanted it. In prime conditions (as I climbed it solo), the first pitch is 4-5 body lengths of AI3- and the second pitch is 1-2 body lengths of AI2 (sometimes it's even just snow that you walk up). Page 191 of the new guidebook "Cascade Classic Climbs" is a good, representative picture of my wife about to solo the "crux" WI3- on TC. You can see that in prime conditions, it is a *very easy* ice step. Without an autopsy, and without knowing the conditions, and without having known Dr. Thurmer personally, it is possible that he got hit by a falling rock and may have been incapacitated to arrest (the worst case and very unlikely scenario). Impossible to know. I don't think TC is notorious for having rock fall this time of year. I have climbed this mountain 8 times in March and April on different years and never observed rock fall. It's possible that he was just really unlucky and got hit by a rogue rock. Norman_Clyde, I think it's very unlikely that Dr. Thurmer would have set up a self-belay at any point, as the pitches do not lend themselves to a self-belay. I have climbed Gib Ledges, and (for comparison), I did not and would not solo that route due to the frequency of rock fall. I think Gib Ledges has much more exposure and much more objective hazard, for reference. The point of me saying all of this is that I personally think there should be zero judgment towards Dr. Thurmer's decision to solo this route. I don't really think there is any "no-fall" terrain on TC, as long as you are experienced with self-arrest techniques. I 100% respect all opposing opinions since everyone has different risk tolerances. My personal opinion, if you can lead WI4 ice clean, roped, and it feels easy, and you also have solid self-arrest skills, TC is a trivial route to solo (coming from a guy who doesn't solo shit).

-

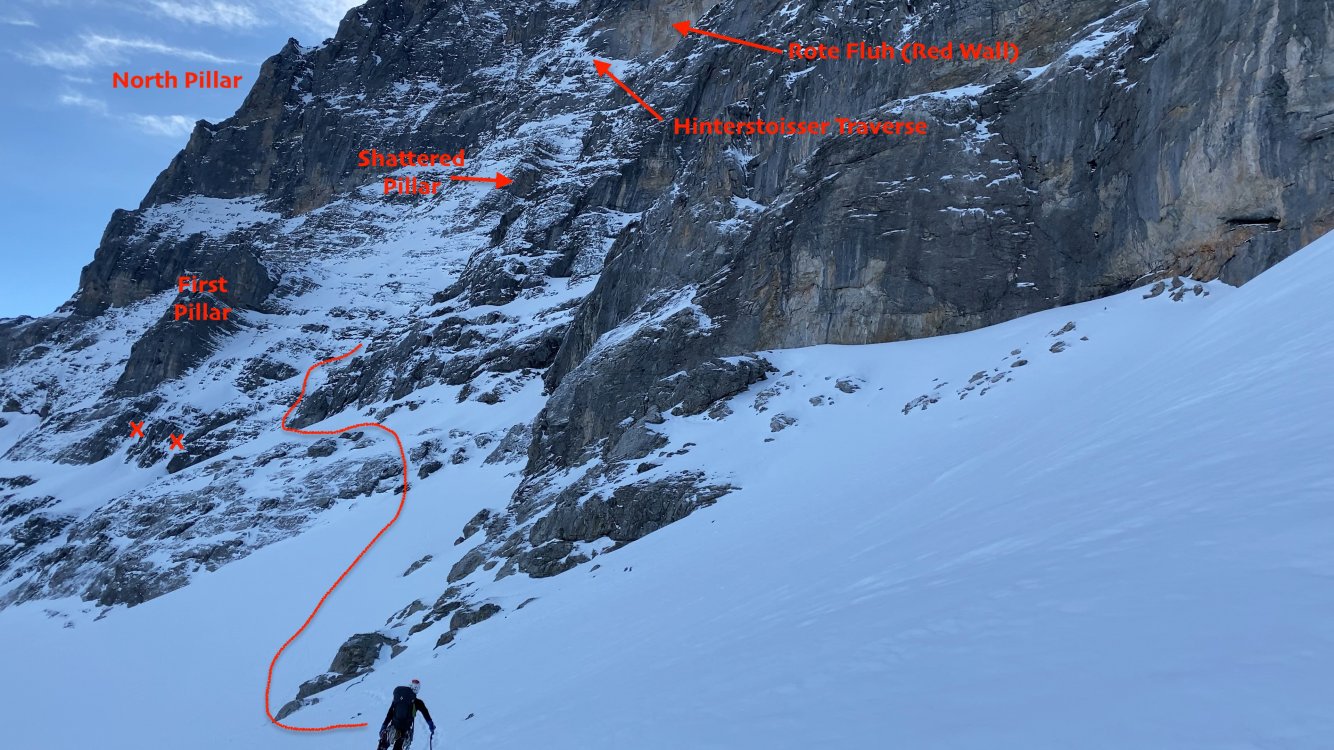

Trip: Goode Mountain - Megalodon Ridge Trip Date: 08/29/2021 Trip Report: Megalodon Ridge. An evocative name for an evocative climb on Goode Mountain, the tallest peak in the North Cascades National Park. Priti and I have been struck by its lore ever since we were students learning to alpine climb. It is another one of those mythical Cascades test pieces that rarely sees ascents (although it really should get more attention). Megalodon Ridge is the East ridge of Goode, joining with Memaloose Ridge and Goode Ridge from the Southeast before it reaches the summit. The climb ascends with foreboding views out onto Goode’s impressive North Face and the highly aesthetic, classic NE Buttress. Put up in 2007 by local legends Blake Herrington and Sol Wertkin over three days with recon by Dan Hilden, we were maybe the sixth known ascent. Dan and Jens Holsten made the second ascent in 2010 over a blistering 27 hour single push. FA TR: https://cascadeclimbers.com/forum/topic/53892-tr-mt-goode-megalodon-ridge-iv-510/?_fromLogin=1 Second Ascent TRs: - http://jensholsten.blogspot.com/2010/09/sound-of-goode.html - https://cascadeclimbers.com/forum/topic/76094-tr-mount-goode-megalodon-ridge-932010/ Other folks who have successfully put their hat in the ring include local heroes of ours: Alex Ford, Laurel Fan, Austin Siadak, Michael Telstad, and Sean Fujimori…all people we have no business having our names in the same sentence…which added to the improbableness of this climb. With new standards in moderate 5th-class choss tolerance, however, I think it’s time to lift the veil on this elusive climb. Named after the prehistoric behemoth of the ocean, fish-themed snacks are a must. 33.5miles and 8,500ft vert round trip make this climb a relatively chill 3-4 day outing, an ambitious 2 day outing if you’re a pro climber, and an unfathomable single push outing if you’re a demi-god. Being mere mortals, we did this as a casual 3-day outing with lots of time to spare. Since its inclusion in Blake’s 2015 “Cascades Rock”, those pages went unconfronted for six years until Michael and Sean posted of their adventure this past July, reigniting its possibility. Michael TR: https://cascadeclimbers.com/forum/topic/104101-tr-mount-goode-megalodon-ridge-07192021/ Michael had an amazing trip report that helped us immensely. The purpose of this TR is to sprinkle in some more micro beta if you choose to have less of an adventure. Strategy Tips The route could feasibly be done in 2 days by a very fast team of folks who are used to covering many miles of trail quickly. But it is actually a very moderate outing when done in 3 or 4 days. I'll outline all bivy options. You never really need to carry much water with you unless you plan to bivy on the summit. We chose to carry less water on the route, and skip the summit bivy, since it's just an hour or two down the SW Couloir to flowing water. The Goode Mountain summit bivy is truly remarkable and a destination in and of itself. There are two ledges at the very top which can fit four, then two more ledges 60m below the summit which can fit four more. Sleeping on top is REALLY COLD, however, and you can get away with bringing less clothes if you don't sleep on top. You really don't need to have a stove on this trip either since there is enough flowing water (unless the daily high's are below freezing in early season). We regret bringing a stove. Save every ounce In all of my anecdotal polling data, nobody has taken the alternate wraparound descent as described in Cascade Rock. Seems to be generally difficult and sketchy, requiring gnarly glacier travel and crampons. Most parties who do the NE Buttress go down the SW Couloir to Park Creek, and it's kind of nice to just take the normal descent and avoid any extra shenanigans. So...recommend just taking the normal descent. There is still some weirdness going down to Park Creek, however, and we had to check our tracks frequently. Many tracks are available on Peakbagger.com You can probably skip crampons and ice axe. The SW Couloir doesn't really require it, although you will find chill snow travel on descent. There is a snow ridgeline along Megalodon Ridge (the ski descent). Depending on the time of summer, you may be on top of the snow, in a moat, or in choss. If you're on top, you can probably get away with just belaying across if you're worried about the exposure. Pair down the weight!! We brought light glacier harnesses and loved it! We clipped gear onto our backpack waist straps and all draws went around the neck. There is really only 4 roped pitches. The descent is between 2 and 6 rappels depending on how much down-climbing you're comfortable with, so you don't really need a regular harness, unless you're bringing more than a single rack. A single rack .2-3 and a few small nuts is more than enough if you plan to solo <5.6 terrain. Bring more gear if you plan to simul. You can even skip the #3 if you are really confident at 5.9. Less is more. Headphones and downloaded podcasts make the 20 mile hike out go faster. Skip the chalk bag. Maybe bring a tiny tube of liquid chalk. If you're confident in climbing 5.8 in techy approach shoes, you could maybe skip rock shoes altogether. Cache beverages at Maple Creek on the way in so you have it on the way out! There are really just 3 mandatory pitches of climbing all stacked on the headwall, and two additional optional pitches (the rest is 4th class and low 5th). To start off, I personally highly recommend roping up at the top of Tower 1 for the downclimb to the first notch since it is megaloose 5.6 downclimbing with mega exposure (Note: the FA party rappelled 50m to the south, not recommended). Then unrope for the traverse up/over/around gendarmes until the headwall pitches (4th class and low 5th). Bypass gendarmes logically via lines of least resistance (sometimes up and over, sometimes around). Rope up for the three headwall pitches to the summit of the SE summit: 1) 35m of LOOSE 5.7-5.10 (depending on which variation you chose), 2) 30m of 5.9 (technical crux of route) with many hand cracks, 3) 70m (simul) of LOOSE 5.7 to the SE summit (you can stop before summit if you don't want to simul). Then unrope again, pass over the "ski descent" snow ridge, downclimb talus Gain the rocky ridgeline again and pass a prominent col (not to be confused with Black Tooth Notch) Continue on the rocky ridgeline, passing a piton and an old sling (5.6), continuing mostly on top of the ridgeline to the final gendarme just before the Black Tooth Notch. Blake describes it as "a pitch of well-protected 5.10 climbing on the north side of the crest down into the notch" (Michael down-graded it to 5.9). We found a 4th class route on the South side (climber's left) which bypassed the gendarme entirely, if you want to lose cool points. Cross over the Black Tooth Notch (the SW Couloir), notice the rap stations, then an exposed traverse (cairn here) meets up with the NE Buttress. Three 30m pitches of exposed and quality 5.6 (angling severely up and right) take you to the summit. We downclimbed the 5.6 back to the Black Tooth Notch, skipped the first rappel at the notch, scrambled down 15m to the next rappel, then made two raps (30m then 15m). I highly recommend not trying to downclimb these two rappels...just take them, it's steep, loose terrain. Approach Start from Bridge Creek Trailhead (just East of the Rainy Pass Trailhead) and take the PCT south, leaving it for the North Fork Bridge Creek trail (this is also the approach for the NE Buttress of Goode). Starting from the Bridge Creek TH instead of Rainy Pass saves an extra mile of hiking. Our downloadable tracks once you leave the North Fork Bridge Creek Trail and getting up on to the ridge are here: https://www.peakbagger.com/climber/ascent.aspx?aid=1748765 Pictured above is the turnoff from the North Fork Bridge Creek trail which matches the tracks. It's an obvious boot pack that quickly turns into easy bushwhacking through alder. This turnoff is approximately when the trail is closest to the creek. Pictured above is the minor bushwhacking (knee to waist) over the creek (hidden) to gain Megalodon Ridge (right side of the frame). The bushwhacking will be much harder if it's just after a rain. When you get close to the creek the bushwhacking goes over head just for a little bit. We took lessons that Michael and Sean learned and stayed on land through the dense brush, heading upstream for ~50ft along the creekbed instead of attacking the creek directly and wading upstream in the icy water. When you pop out onto the creek, don't get in the creek until you confidently see your egress point. You don't want to spend more time in the creek than necessary. I got screaming barflies just from our straight-line crossing. If you don't see the super obvious exit point (circled in red above), keep plowing upstream through the dense brush. Once on the other side of the creek, a little more bushwhacking takes you to a rocky stream bed which you follow for a ways until you reach a chockstone waterfall (get water here). You have 2-4hrs until you reach water again (approximately 1/4) up the ridge, so you don't need to carry too much. Chockstone Waterfall. Follow ledges high and right until it opens up. Follow the stream until you get to the chockstone waterfall (where the green track diverges). Cross the creek over to the North (Megalodon) side and skirt the the top of the canyon wall until it opens up...don't go straight up the ridgeline. Follow open slopes up to the top of the ridgeline until you get to a small saddle and a 5.4 buttress. This 60m buttress is super loose and scary, so spend some extra time looking for a safe route up. Above the buttress is a few more hours of 4th class hiking and scrambling to the top of Tower 1. There is mild exposure on the final ridge to the top of Tower 1, but it's easy climbing. From the top of the buttress to the water are several really good bivy sites. At the water source is flat snow and boulders (not really a good, dry bivy site), so find something lower down on the ridge and hike up to retrieve water. This is the last flowing water until the Goode High Camp basin below the SW Couloir (1-2hrs after reaching the summit), so fill up a day's worth or more if overnighting on the summit. You also have the option to melt snow at "ski descent" along the way if you chose (no flowing water here). 4th class ridge to the top of Tower 1. Looking over onto the North Face and the awesome NE Buttress route. Neat pic. Pano of Memaloose Ridge as it meets up with Megalodon at Tower 1 on the right. From the top of Tower 1. The "headwall" is on the left (SE Summit) which contains three roped pitches. The FA party rappelled 50m to the South then traversed to the notch (not recommended). Other parties since have downclimbed. The downclimbing is loose, exposed 5.6...highly recommend roping up! You can unrope again down at the notch (~2 rope lengths). Unroped, easy scrambling up/over/around several gendarmes to reach the headwall. The traverse from Tower 1 to the SE Summit Headwall. Once at the headwall, choose your own adventure. The first pitch is 30-60m (depending on how high up you start belaying) of 5.7-5.10 climbing. Belay under an obvious corner on a ledge. The second pitch is quality 5.8 or 5.9 (the technical crux of the route) hands and fists for 30m to a ledge below the final ridgeline to the summit. The third pitch is 70m of unprotect able 5.7 ridge climbing (stacked, loose blocks) to the SE summit. You can stop short of the summit if you don't want to simul. Blake suggested the SE summit as potentially a good bivy, but I didn't see anything that looked mildly comfortable. Press on to the summit or the Goode High Camp. Looking down from the belay at the top of Pitch 1. You can see the ridge traverse down to Tower 1 (center), Megaladon Ridge (left), and Memaloose Ridge (right). Could be a neat trip to take Memaloose into Megalodon Ridge! Looking up at pitch 2. Start in the corner and traverse left. From here we unroped for the rest of the way (and we're not very good rock climbers either). You can also put on your approach shoes for the talus. Cross over the snow (it is all choss now). Melt snow here if needed, no running water. Downclimb talus and start back up the ridge, staying mostly directly on the ridge. The final obstacle is a gendarme guarding the Black Tooth Notch. Go right (North) for the 5.10 original route (5.10 or 5.9) or downclimb and go around left (South) for our 4th class cheater-bypass route to gain the Notch. Once at the Black Tooth Notch, traverse right (North) to join the NE Buttress. Climb 3x 30m pitches of quality, exposed 5.6, trending right to reach the summit. You can then make 3 traverse-y rappels back down to Black Tooth Notch or downclimb. Recommend taking two rappels down Black Tooth Notch (30m, then 15m) since it is very loose and steep. Here is a really good description of the descent: https://engineeredforadventure.com/goode-mountain-northeast-buttress/ Looking back at the final gendarme before the Black Tooth Notch at the two route options (photo taken from Black Tooth Notch looking East). Photo of the entire Megalodon Ridge! By now, you should be able to pick out "Tower 1", "SE Summit", and "final gendarme". I'm not going to overlay them for you . The photo is taken from the ledge traverse on the North side looking back at Black Tooth Notch. Another view of the "final gendarme" and the 5.9/5.10 downclimb on the North (shady) side that we did not do. Fish-themed snacks are mandatory. Looking up from the normal descent towards the SW Couloir. A long, but straight-forward descent down to Park Creek Trail and 20miles on trail back to the car. There is a good High Camp bivy site with water in the basin below the couloir: N 48.48025° W 120.91991° Gear Notes: single rack .2-3, few nuts, 8 single alpine draws, 3 double alpine draws, light glacier harness Approach Notes: Tracks: https://www.peakbagger.com/climber/ascent.aspx?aid=1748765

-

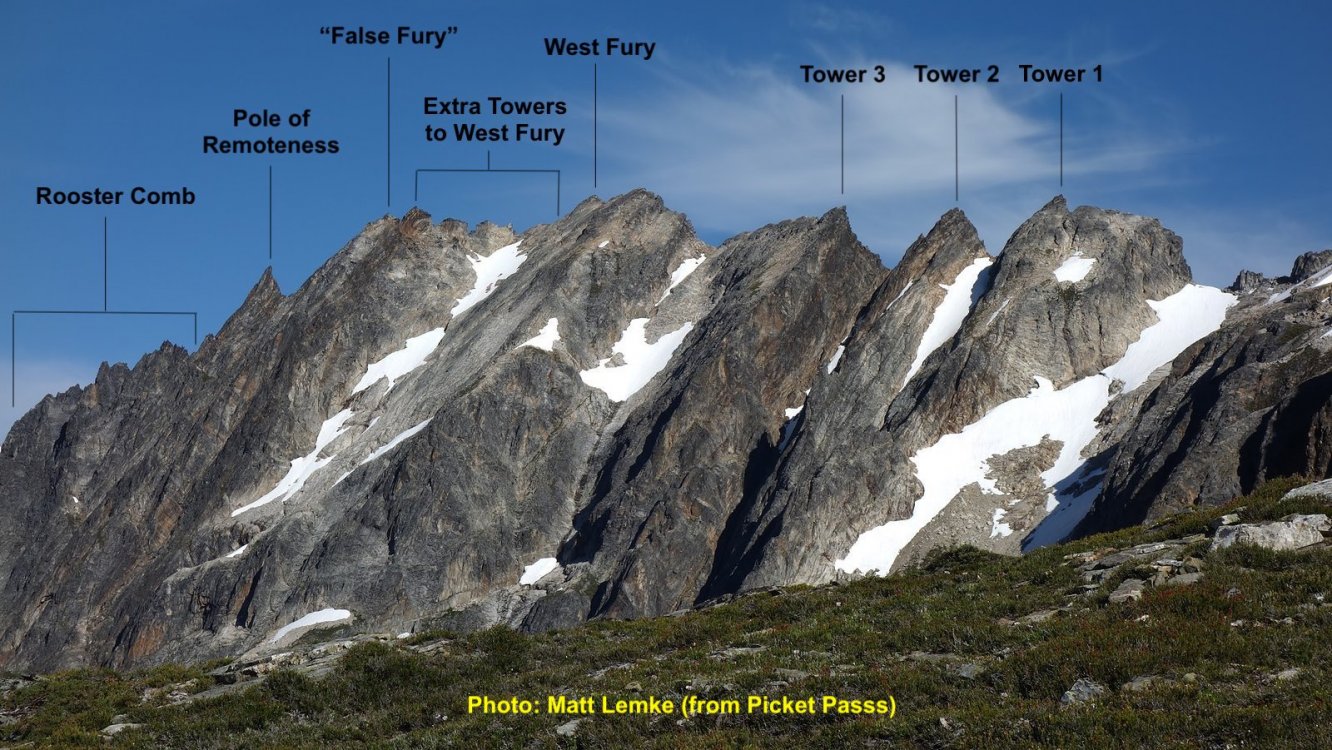

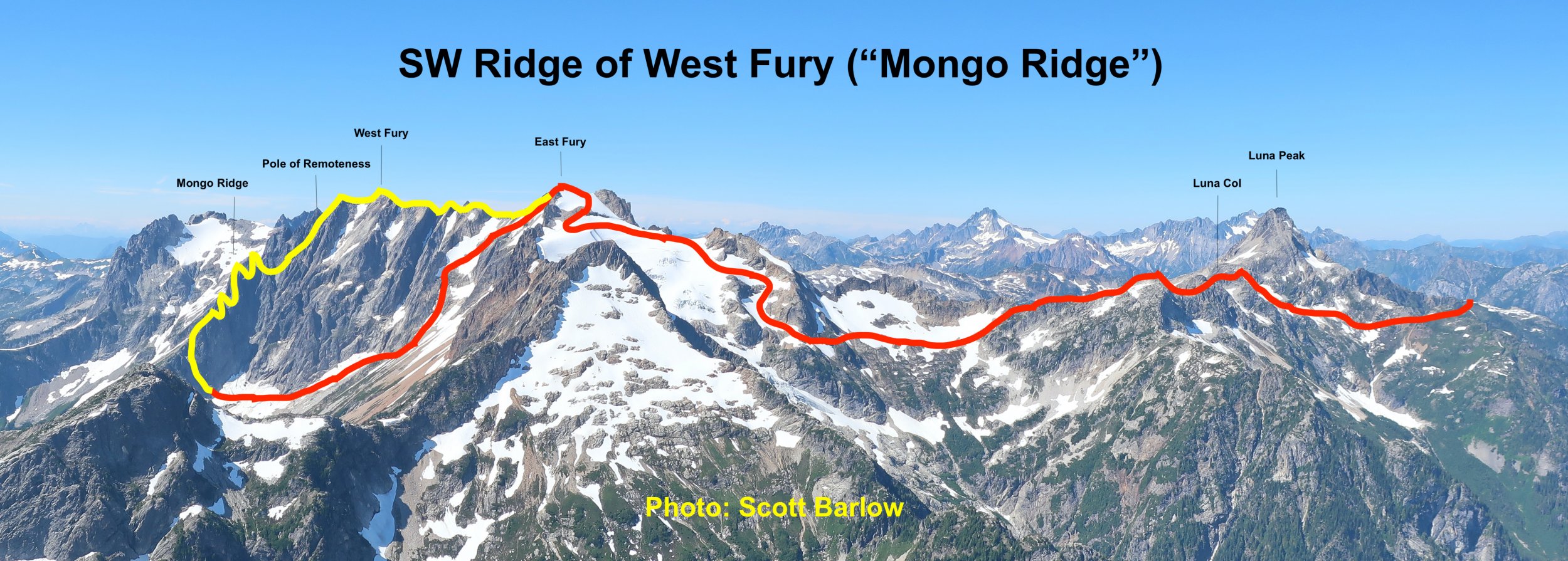

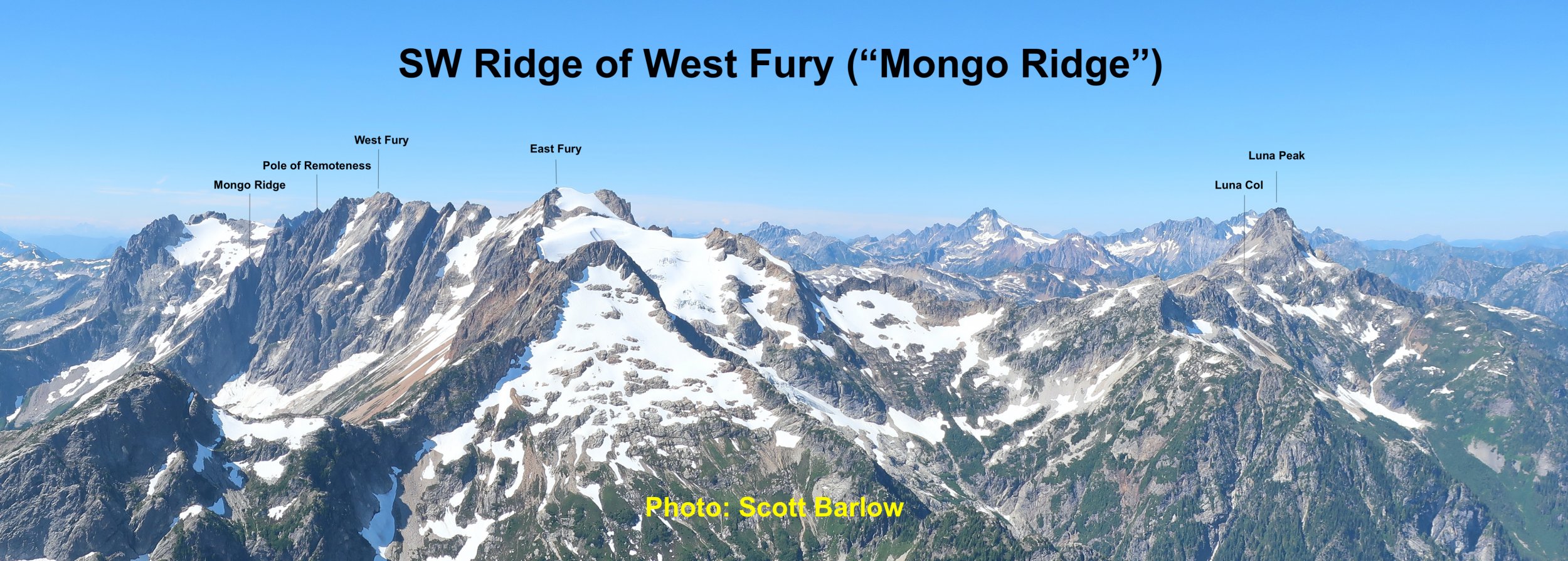

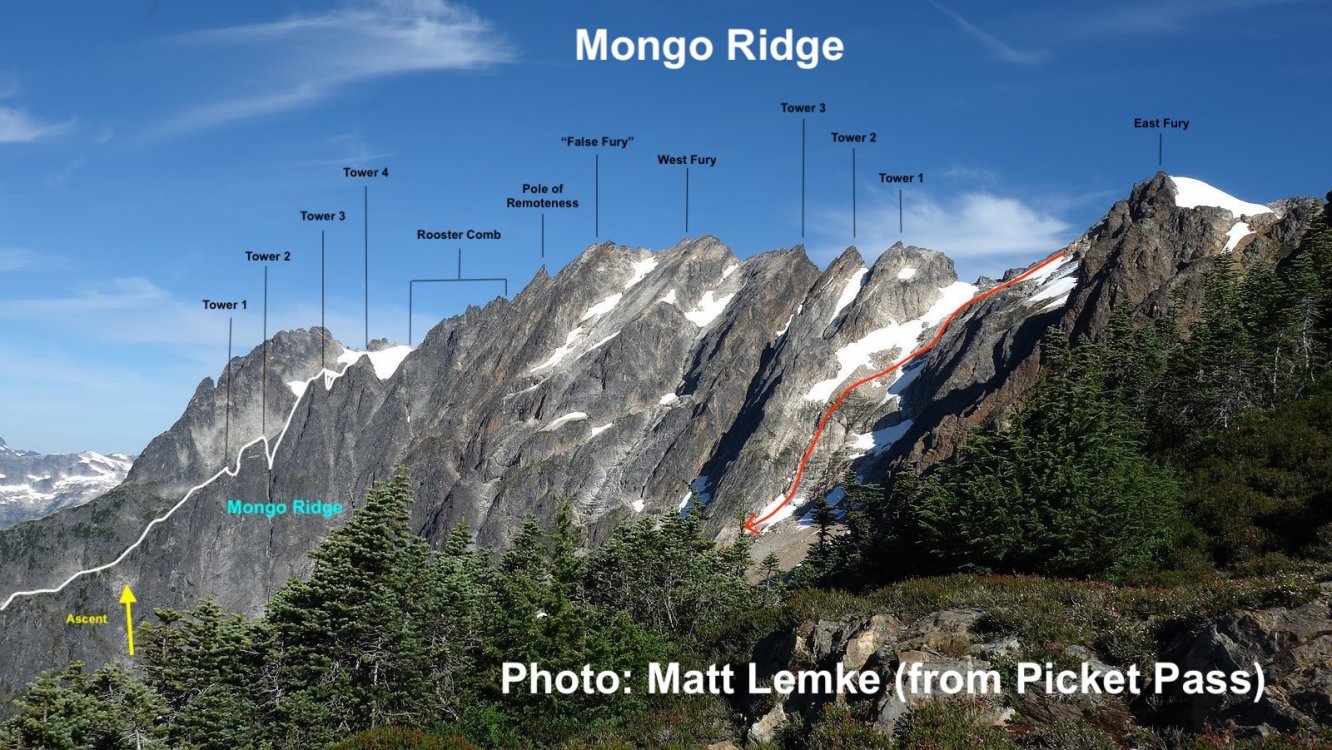

Trip: West Fury - Mongo Ridge Trip Date: 07/05/2021 Trip Report: In our relentless pursuit to ride the coattails of THE Wayne Wallace, Priti and I made the second ascent* of Mongo Ridge (the SW Ridge of West Fury in the Northern Pickets of the North Cascades). It is a Stegasaurus ridge which rises 4,000ft over a mile from Goodell Creek punctuated by thick clusters of gendarmes that look like they’re straight out of the Karakoram. [*2024 Update: Since our ascent, two more parties have ascended the SW Ridge of West Fury (total of four ascents as of July 2024, detailed below)] August 26-27, 2006: Mongo Ridge First Ascent Wayne Wallace (solo) making one bivouac past the Rooster Comb and Pole of Remoteness (with all of the route's technical climbing completed). Legend! https://waynewallace.wordpress.com/2014/05/ July 5, 2021: Jeff and Priti Wright make the Second Ascent of SW Ridge of West Fury, following Wayne's line of ascent but bypassing both the Rooster Comb and the Pole of Remoteness. They did not bring bivouac gear on route (bad call), and they did not make any bivouacs on route. Camp-to-camp in 23hrs from the summit of East Fury (base camp). July 11-13, 2022: Sam Boyce and Lani Chapko make the Third Ascent of the SW Ridge of West Fury, following Wayne's line of ascent, taking Jeff and Priti's Rooster Comb bypass, making the second ascent of the Pole of Remoteness (following Wayne's approximate 5.7 line), and making two biouacs on route (base camp at Luna Col). https://www.theclimbingguides.com/post/mongo-ridge-and-the-pole-of-remoteness-7-09-2022-7-14-2022 Early July, 2024: Emilio Taiveaho and Adam Moline make the Fourth Ascent of the SW Ridge of West Fury, following Wayne's line of ascent including the Rooster Comb (second ascent) and the Pole of Remoteness (third ascent, and by a new line of two pitches of 5.9R) making them the Second Complete Ascent of Wayne Wallace's Mongo Ridge! https://cascadeclimbers.com/forum/topic/107832-tr-mt-fury-wayne-wallace’s-mongo-ridge-second-ascent-of-the-rooster-comb-and-new-line-on-the-pole-of-remoteness-07072024/?fbclid=PAZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAaZGeT7NzsHS7Pk4D4-BEz-9Fi4D7NGD8mzAiVTHkasQ-41sIDl0dhUtNzM_aem_PLTVnZmmLRYxsTBP00Ynuw#replyForm We first heard about Mongo when Wayne came to speak for a BOEALPS - Boeing Employees Alpine Society Banquet in 2015 and regaled a captive audience with his bold adventures. We warmed up Wayne's feature presentation with a talk on our trip to Patagonia climbing Aguja de l'S. Then Wayne came on stage talking about Mongo, making de l'S look like a mole-hill. Wayne climbed this route in 2006 SOLO, like a boss, questing into unknown terrain that easily could have landed him into mandatory hard free climbing. With vertiginous cliffs on both sides, he knew that bailing from the route was not an option and that he had to climb whatever the mountain presented. The difficulties on the route were up to 5.9, with an additional 5.10b pitch (a routefinding error), but the towers presented possibilities up to 5.11 if we weren’t lucky enough to have Wayne’s beta. The first ascent is one of the legendary, mythical ascents of the Cascades and even of the climbing world. After 15 years, only a handful of folks to my knowledge have even considered attempting it again. The bottom half of the ridge has four narrow towers which require you to summit and rappel in order to make vertical progress on the ridge. Long, double-rope rappels and hard technical climbing discouragingly makes it take hours just to ascent 100ft at times. Above these four towers are the “Rooster Comb” and the “Pole of Remoteness” (named by John Roper who figured it was the hardest place to get to in the lower 48). After Tower 4 and before the Rooster Comb, we scramble traversed low around each of these features and did not summit the Pole of Remoteness since it was getting dark and we did not bring bivy gear. At Wayne’s suggestion, we planned to climb camp-to-camp which was situated at the summit of East Fury. This means that while we did ascend the topographic feature of Mongo Ridge to the summit of West Fury, we did not truly climb “Wayne Wallace’s Mongo Ridge” in the manner that he climbed, including many more pitches of technical terrain. When we talked to Wayne in 2019, I told him that “Somebody needs to repeat this route, just so the world can understand what you accomplished.” It’s impossible to understand the scale of this route without being on it, competing as “one of the largest features on any mountain anywhere.” “You have to climb a major mountain [East Fury] just to start a most major climb.” Even with Wayne’s pictures and descriptions, we were still filled with dread as we attempted to route-find up each tower. While I am proud of what we did accomplish, I am still shaken at the boldness and audacity of the first ascent. Our tale should be considered a celebration of that event. Wayne called it Alpine Grade VI, but Beckey downgraded it to V deeming it (incorrectly imho) similar in commitment to Slesse NE Buttress (ref. Cascade Alpine Guide Book 3, pg. 118). We concur with Wayne's Grade VI rating, although I won't be even slightly offended if anyone wants to challenge the grade while ensconced in sofa cushions. Our itinerary: -7/3/21: 2PM boat ride from Ross Lake Resort to Big Beaver TH. Bivy in Access Creek basin. -7/4/21: Access Creek Basin to East Fury Summit. Left summit bivy in situ. -7/5/21: 23hr day camp-to-camp including Mongo Ridge and the traverse from West Fury to East Fury. -7/6/21: East Fury to Access Creek Basin -7/7/21: Access Creek Basin to Big Beaver TH. 2:30PM boat back to RLR. Here are collected links regarding Wayne's FA, for reference: https://waynewallace.wordpress.com/2014/05/ http://www.alpinist.com/doc/ALP19/climbing-note-fury https://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/21/sports/othersports/21outdoors.html http://www.alpenglow.org/nwmj/07/071_Mongo.html http://publications.americanalpineclub.org/articles/12200713002?fbclid=IwAR0iS9vNBvJ1XUQPOTPIXy8eymiTsuWFHI5TJtuAvLJUNb5LknfgeYgTriI Scurlock Picture: https://www.pbase.com/nolock/image/65948954 I won't go through too much detail on our approach to Luna Col and East Fury, since it is detailed well in many other places: https://onehikeaweek.com/2020/08/02/mount-fury/ http://www.nwhikers.net/forums/viewtopic.php?t=8021967 (specifically useful here is the traverse from East Fury to West Fury) Since we planned to do the route camp-to-camp (situated on the summit of East Fury), we studied the traverse from West Fury to East Fury in detail since we figured we'd be onsighting it in the dark to get back to camp. I will point out the "Red Ledge" (pictured above) just past Luna Col is reached by staying directly on the ridgeline from the col to begin the traverse over to East Fury. Past the Red Ledge, the next tower (called "Crux Tower" in some reports) is ascended directly via 4th class ledges and short 5.4 steps. A rope and gear would not be useful here. There is significant foreshortening here, as the route looks much more accessible as you get closer. Unless you're climbing in Winter or Spring, you will not be able to get across the bergshrund (as shown in the Beckey overlay), but instead will traverse left then right to reach the summit arête. Furthermore, the approach to the base of Mongo Ridge from East Fury's summit as discovered by Wayne is the easiest approach. While it is possible to reach Mongo's base via Picket Pass (either by navigating over Outrigger Peak "Southeast Peak" or Otto-Himmel Col), these approaches would be significantly more effort...or bushwhack for days up Goodell Creek. As you approach, notice the grey washboard streak with an overhanging gully. The route will start to the right of this feature. The 4,000ft descent from East Fury's summit may involve a lot of slab if the snow levels are low. We regret not bringing bivy gear on route. An alternative itinerary could be: -Day 1: Big Beaver TH to Luna Col -Day 2: Luna Col to Mongo Ridge Tower 1. Option to leave stove and tent on East Fury Summit as you pass by. There are no good bivouac sites on route. Just bring a sit pad and a sleeping bag and open bivy if splitter forecast. -Day 3: Tower 1 to either East Fury or Luna Col. A note on weather: The Pickets have notoriously unpredictable weather. Even with a splitter forecast, you can still have rain or even storms. Consider a tarp as backup shelter. Crossing the moat is the first crux. The moat is huge! Only found one place where it touched the rock slightly. On the approach, don't come down anything you can't go back up! Here I had to cross a giant moat (unprotectable compact snow), using both Gully tools (then passed the tools down to Priti). A picket here would have been very useful...but that's a big cost. Might have to bury a tool and rap/swing across the moat. Tower 1 was a TIME KILLER! Wayne reported a 5.8 overhang crux which we did not find. Instead we got suckered into a runout 5.10b overhang in the grey washboard gully. Recommend future parties to avoid this gully completely, and instead stay on the face to its right. Our second mistake was getting suckered into a difficult 5.8 grassy gully. Wayne later clarified that he immediately captured the ridge first, then went straight up the ridge (recommended). We started in an obvious chimney (5.6), gaining the face on the left then going right (many variations). After the chimney, we went left to the 5.10b overhanging grey gully instead of going up. It looked harder to gain the face above, but it is 5.8 if you can find Wayne's Way. The slopes to gain the ridge are all STEEP. We breathed a sigh of relief once we were on situated on the upper slopes of Tower 1, but route finding continued to be a challenge. A 30m rappel took us down to the notch between Tower 1 and 2. It seems possible to bail here back down the glacier and back up to East Fury. Perhaps the last legitimate bail option, so we considered the time and knew we would be climbing through the night. Tower 2 is only 2 pitches of 5.7 with no real route finding difficulty and went pretty quickly. The rock is REALLY loose however, so I was careful not to knock anything down on my belayer. Route lines are all approximate by the way! The first double rope rappel from Tower 2 led to the notch between Tower 2 and Tower 3. Tower 3 is the technical crux of the route and another TIME KILLER! It takes hours just to gain 100ft elevation. Once atop, it's demoralizing to look down and see the top of Tower 2 so close. Wayne reported a 5.10a bulge which I think we avoided by staying on and just right of the ridgeline. From the notch between Towers 2 and 3, a 5.4 traverse gains a grassy belay with 5 more pitches above ( 5.9 30m, 5.9 30m, 5.9 30m, 5.9 50m, 5.6 65m). Priti stopped whenever she found a good belay spot. We also hauled packs on 4 pitches expecting 5.10a climbing at any moment. It was real 5.9 climbing, consistently on decent rock for four pitches. Next time, instead of hauling just load everything into the follower pack and leave the leader with a mostly empty backpack instead. We took two backpacks on this climb to evenly distribute weight and bulk while simul-climbing. This was a good method. We consistently trended right above the belay. Higher Hiiiiiigher Hiiiiiiiiiigher Another 60m rappel deposited us to the notch between Towers 3 and 4. Finally, we got through the technical crux and we were losing sun fast! We knew we were in for an open bivy or a heartbreaking omission of the Pole of Remoteness. Tower 4 is another quick one. Two pitches, 5.9 then 5.7. It looks like really hard climbing going straight up! Instead we followed Wayne's advice and traversed out right for ~20m on 5.9 terrain with decent protection, then up following flakes and grass to a good belay. As you start climbing up, the climbing doesn't ease up, but instead is engaging, fun 5.9. Then 65m simul-climb to the summit. A final 50m rappel down to the base of the Rooster Comb. We were a bit confused here since the terrain opened up into a minefield of gendarmes. The Pole of Remoteness was indistinguishable among all of the towers. We knew we had to boogie so we took all the shortcuts that we could find. We noticed that the Rooster Comb could be bypassed on the right on low-5th terrain by taking another 30m rappel, then down climbing and traversing its Eastern flanks to a grassy gully. Wayne went up and over the Rooster Comb, not realizing there was a bypass. The Rooster Comb is very complex with several small flagpoles that required rappels. Wayne describes the final rappel off the rooster comb as a "diagonal rappel" that you can redirect off of horns, after which he flicked the rope to retrieve. There are at least two more intermediate gendarmes between the Rooster Comb and the Pole of Remoteness that we skirted around. Wayne found himself on their left side while we were on their right side. Wayne captured the upper 4th class slopes via a grassy gully (shown above). From here it's all 4th class to the "False Fury" summit. I coin the label "False Fury" because we stared at this point almost along the entire route thinking it was the West Fury Summit, but instead is fairly far from the true West Fury summit. Above is pictured our Rooster Comb bypass route which required an additional 30m rappel (or easy down climb). This was the first time we encountered snow on route, but don't count on it being there! Bring 4L water each. Southern Pickets in all their glory. Wayne traversed around the right side of the Pole of Remoteness to reach the col and summit it from the backside. To climb it directly would probably be 5 pitches of hard, loose climbing. From the notch between "False Fury" and the Pole of Remoteness, Wayne reported 1 pitch of 5.7 to reach the summit of the PoR. There is no anchor on top, so he threw a rope around a loose block and solo downclimbed, using the rope as a backup. If you are a team, consider downclimb-belaying. We sadly felt the need to skip the pole since it was total darkness by the time we got to the notch with a lot of traversing left to go. Once atop "False Fury", we couldn't find the summit register and realized that the real West Fury was maybe .25miles away separated by 4 more gendarmes, first downclimbing (or rappelling) down and right and traversing around the first gendarme, then weaving up, over, and around the others to finally reach the real West Fury summit. Glad to have put in the time to memorize the traverse beta between West and East Fury, it went off slowly but smoothly. One piece of key beta was at the end of Tower 1 (the last tower between the Fury's), you can find a secret 4th class ramp around to the North (climber's left) to find the rappel station that leads to the final push up the slopes back to East Fury. This is a 30m rope stretcher rappel, by the way! Thanks to Wayne for all of your support and encouragement! I think this route is more of a classic in the way that Hummingbird Ridge is a classic. We should really just sit back and marvel at the first ascent. It's a true Picketeering adventure, but loose rock, lack of bail options, and lack of bivy sites is pretty discouraging. The Pole of Remoteness still needs a second ascent, however! But it would a pretty doable day to get to PoR in-a-day from your East Fury bivouac by traversing high along the ridge and scrambling down from "False Fury", then reversing the route. Gear Notes: Single Rack .1 to 2, doubles .3-.75, small cams (TCU 00, TCU0). We like small cams in the Pickets! Small rack of nuts. 1 screw and 1 V-threader for glacier (didn't use). 60m single rope, 60m pull cord (three long rappels + optional pack hauling), 1 Petzl Gully (technical light ice axe) each, 10 single alpine draws, 3 double alpine draws, 1 quad, 50ft 5mm cord for rap anchors (used it all), left three caribeeners on rappel stations, steel horizontal front-point crampons. Approach Notes: Boat from Ross Lake Resort to Big Beaver Creek - Access Creek - Luna Col - East Fury - 4000ft descent on South side - Mongo Ridge - West Fury - Easy Fury

- 16 replies

-

- 12

-

-

-

-

- tripreport

- cctripreport

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

[TR] Darrington - Squire Creek Wall -> Buckeye -> Whitehorse 06/19/2021

JeffreyW replied to Kyle M's topic in North Cascades

Holy cannoli! This is an epic trip you two! Bravo. Takes creativity and vision to dream this one up. Probably not many people understand exactly how crazy hardcore this is. Next level. Chapeau. -

[TR] Wai‘ale‘ale - Alaka‘i Swamp 12/01/2020

JeffreyW replied to JeffreyW's topic in The rest of the US and International.

Ha! That's a good way of putting it! Still can't believe you biked and hiked the whole dang thing in a day. Total badass. I was so nervous and intimidated about this hike, and it ended up just being good Type I fun. Couldn't do it in a day though. The video of crash landing and the proceeding 30min of untangling lines from the ferns will remain in the vault forever. -