Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation since 03/18/24 in all areas

-

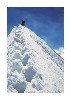

Trip: Mount Rainier - Ingraham Direct Trip Date: 03/17/2024 Trip Report: Mount Rainier in calendar winter... 👻👻👻 Whooooo oooo ohhhhh 👻👻👻 Scarry Well, this wasn't like that. With the big first warm-up of spring predicted, NWAC was saying considerable at all elevation bands everywhere due to wet slides. This actually made a calendar winter climb of Rainier seem spot on for the weekend of St Patrick's Day. Me and @Albuquerque Fred headed out hoping for an easy nab. So that I could get some extra sleep and to let the gate opening crowds thin out we left Seattle at 9:00, getting to Paradise close to noon. The ranger at Paradise (where we self-registered) literally said "you should have no problems"! This was extremely surprising after getting used to rangers telling you how scary and dangerous everything is, assuming that you are getting in way over your head. I think this may have had the opposite effect and made me nervous. It was 68° in the parking lot at 12:30 p.m. We slogged uphill passed about 400 people, mostly snowshoeing in jeans, good for them getting outdoors though. I think it was due to the heat but we felt like we made awful time getting to camp Muir but upon further reflection it took 4.5 hours which seems respectable with overnight packs. There was one other party of four staying at the shelter that night, they were going to bed extremely early for an Alpine start, so we hung out outside in the warm weather making water and cooking and eating and watching the sunset. We turned in at a halfway reasonable hour for a 4:00 a.m. wake up. At 4:00 it was indeed quite cold, especially after my pad went flat and I had to blow it up like five times. The prediction was for low 20s° weather, that seemed about right. We started hiking at 5:15 with our skis on our backs in the pitch black. It was cold, but calm. Booting up Cathedral Gap got me mostly warmed up, and it started to get a little light by the time we crested the ridge. I was taking diamox for the second time on Rainier (the second with diamox that is), and I didn't realize it but tingling in your fingers is a side effect, I thought they were very cold all morning but I think there was just extra blood flow. It felt a lot like light duty screaming barfies though. The sun rose right when we hit Ingraham Flats right around 11k, it was stunning. The going was hard, punching through breakable crust while booting, but it seemed like skinning would just be icy and scary, and the crust was intermittently supportable. The perfect conditions for disheartening travel, right when you think you are making headway on top of the crust you start breaking through, then you have to put extra effort into stomping the crust down so you don't pitch forward. There were two crevasses, one we stepped over, and the other had a nice stable bridge/plug. We went straight up the gut although I think climber's right is actually more filled in. We made slow progress up to 12,200' where we briefly tried to skin, but it immediately was supportable and icy and steep and scary, once I got to a place I could get out of my skis I did so with gratitude. Due to the hard going we decided to hang a left off the Ingraham Glacier to gain the upper part of the Gibraltar Ledges route and follow the other party's boot pack. There was some minor crevasse dodging here at the ridge crest but nothing challenging, then we followed the boot pack to the summit passing the other party on their way down. The head wall above 12800' above Gibraltar Rock was easy cramponing. As soon as the sun came up it had started to get extremely warm, the bowl of the Ingraham Glacier was absolutely roasting, I was wearing long underwear and couldn't really take it off so I was down to just a sunshirt on top with no gloves and no hat all the way from about 12K to the summit. I summitted in a sweat soaked sunshirt, there was basically no wind the whole way. The crux of the entire climb was definitely the heat, it sapped us pretty hard and made for slow going. This was also very unexpected so it was hard to convince yourself you needed to shed a layer. We were very far behind schedule after almost 7 hours camp to summit, so we didn't linger, we stripped skins, put our skis on for the first time in hours and headed down. I found the skiing to be very challenging for the top 1000 ft on hard packed sastrugui, with the occasional hard-packed smooth pocket that made for easy turns. At about 13,000' there was a long smooth steep head wall that made for great linking turns, though very fast and icy. From here down I found all of the skiing to be quite excellent all the way back to camp Muir and below. With the heat the snow from about 12,800' and below was creamy on top, but still supportable. I made it to Muir with my skis on. Fred is less into sketchy, bumpy, icy, exposed turns, so he found the whole thing much less enjoyable. I guess it's just a matter of taste. We packed up camp and headed down. The snow below Muir was excellent until 6700' were a bad case of mashed potatoes set in. It didn't really matter anyway as this was boot packed out 50 ft wide, so we just survival skied the boot pack back to the sign-in hut, and eventually the car. From summit to car with 30 minutes of packing was 3 hours. It all goes to show you that "calendar winter" is total BS and everything should be based on conditions rather than man-made dates. I found this trip to be a more challenging ascent than the Emmons Glacier was in the spring last year, due to the hot conditions and punchy crusty snow. Gear Notes: Avalanche gear, crevasse rescue gear, 2 30m ropes, sleeping gear (no tent, but a pad with a hole in it), way way way too many clothes, not enough water. Approach Notes: Show up late and skip the gate line, it only takes a third of a day to get to Muir, and what are you going to do before it's reasonable to go to bed anyway? It was a bust day on Saturday: Nice sunset though, views all the way to Jefferson: Fred slogging on the Ingraham: Sunrise: Fred finishing it off: Warm summit break:6 points

-

Hello climbing community! Three of us climbed Rainier this past weekend via Gib Ledges on ascent and Ingraham Direct on descent. Gib Ledges were in good condition - adequate snow; however, in few spots with exposure snow cover is thinning out. Hopefully this weekend will supplement what is there. On Ingraham Direct I counted seven crevasses that we crossed - stepped over, with bigger one of them 2 feet wide. This route will be intact for a while. Above 12500, crevasses are well filled in, making for direct climb up. Besides our team, this past weekend another two groups of two on skis summitted. Good luck!5 points

-

Trip: Kangchenjunga - SW Face Trip Date: 06/01/2023 Trip Report: Kangchenjunga (28,169ft/8586m) Highpoint of India Third highest mountain in the world June 1, 2023 Eric Gilbertson On the summit (photo by Anna Gutu) May 27 – Heli from Kathmandu to Lukla, delayed by bad weather in Lukla May 28 – Heli to Tapethoke village, delayed there by bad weather May 29 – Heli to Kangchenjunga basecamp May 30 – Climb to camp 2 May 31 – Climb to camp 4, start for summit 7:30pm June 1 – Summit 5:30am, descend to basecamp June 2 – Heli to Taplejung, jeep to Suryodaya June 3 – Jeep to Bhadrapur, flight to Kathmandu June 4 – Flight to US Location of Kangchenjunga Kangchenjunga is the third highest mountain in the world and straddles the border between Nepal and India. It is officially the highest mountain in India, but is closed to climbing from the India side for religious regions. So it is only climbed from the Nepal side. The name means “The five treasures of the high snow” and indeed the peak has five sub summits. This very often leads to confusion with climbers taking routes to a summit that is not the true highest point. Aside from routefinding issues, the normal route to the summit is technical with steep rock and snow sections. I was in Nepal for the spring and my goal was to climb Mt Everest and Kangchenjunga. I’m working on climbing country highpoints and this would theoretically get the highpoints of China, Nepal, and India. The normal climbing season for both peaks is mid/late May, and it is difficult for me to get time off this time of year due to my teaching schedule. So if I could get time off for one peak I might as well try to squeeze them both in. The route I officially got time off to climb Mt Everest, so I needed to go for that one first. Then if I happened to finish that climb early enough, was still feeling ok, and the monsoon and high winds hadn’t yet started yet, then I could give Kangchenjunga a shot. I would theoretically already be acclimated so Kangchenjunga should only take a few extra days to climb. I arranged logistics with the cheapest company I could find, Seven Summit Treks, and paid for basecamp services for each peak and helicopter transportation between basecamps. I was planning to climb both peaks without supplemental oxygen and without personal sherpa support, just on my own above basecamp. This was mostly to save money so I could afford both peaks in the same season. I had previously climbed K2 this way in the summer of 2022, so the strategy seemed feasible. Climbing with supplemental oxygen and personal sherpa support significantly increases the price. Flying out of Kathmandu Three partners – Matthew, Steven, and Darren – would join for Everest, but I would be on my own for Kangchenjunga. On May 22 I made my solo no O2 summit attempt on Mt Everest, but had to turn around at 8500m after showing signs of HACE. I had been troubled by a dislocated shoulder in the Khumbu Icefall, two weeks of being sick from a respiratory infection, and not enough time for all the rotations I had intended. Unexpected wind had then delayed my summit push making me spend 40 hours above 8000m without oxygen and pull two consecutive all-nighters before moving up from camp 4. It seemed like luck was not on my side that attempt, though I did make it back down unscathed to basecamp with just a bit of sunburn on my nose. The Khumbu Icefall was effectively closed a few days after I descended (ie all ladders across crevasses were pulled), meaning there was no time for another attempt, unfortunately. After hiking two days down to Lukla I caught a late-morning flight to Kathmandu May 26 and considered my options. Flying to Lukla I was using weather forecasts from professional meteorologist Chris Tomer, and he told me there was still a summittable weather window on Kangchenjunga in late May and early June. It appeared the weather on Kangchenjunga was a bit different than on Everest, since the Everest season effectively ended May 26 due to increasing winds. I had already paid for permits, transportation, and logistics support for Kangchenjunga. And I was already acclimated. The elevation I had reached on Everest was approximately the elevation of the summit of Kangchenjunga. The only potential reasons not to go were that I was still exhausted from Everest and the hike out, and I might end up being alone on the mountain. But I had heard that a group from Elite Expeditions was planning to head from Everest directly to Kangchenjunga, so I wouldn’t be alone. And perhaps if I rested a few days I could regain some energy. I met in person with Dawa and Thanes from SST shortly after landing. It turned out there were currently two solo no-O2 clients of SST in trouble on Everest and Kangchenjunga and rescue teams were being sent to help. Suhajda Szilard, who I knew from basecamp and some of my rotations, had attempted to climb Everest solo with no O2 two days after me on May 24 but had not made it down. He was last seen laying down below the Hillary Step. SST was scrambling to send a rescue team to find him (the search would end up being unsuccessful). Also, skier Luis Stitzinger had failed to return from his solo no-O2 summit bid on Kangchenjunga also on May 24. SST was currently organizing another rescue team to look for him (he didn’t survive and his body was later found at 8300m). With this situation unfolding, understandably SST did not want another solo no-O2 client up on one of those mountains. I was told I needed to go with sherpa and supplemental oxygen. I was confident I was acclimated enough to summit without oxygen, but it appeared my options were to either summit with oxygen and personal sherpa or go home and lose all the money I’d already spent on permits and logistics. Grounded in Tapethoke village It would cost another $11k to hire sherpa and oxygen for Kangchenjunga, and I could just barely afford that if I zeroed out my bank account. That would be cheaper than losing all the money I’d already invested and then paying more a future year to come back, so I reluctantly agreed. Dawa made some calls and indeed a team of four clients and eleven sherpas from Elite Expeditions was planning to helicopter to basecamp the next morning and start a summit push. I would have the highest chance of success if I went on the same schedule as that team. I would go with Pemba Sherpa and he would bring three oxygen cylinders for me to use on summit day. He would bring a spare regulator and he knew how to fix any issues with the system. Approaching basecamp So I had that afternoon and evening to quickly cram in some resting and eating before heading out at 5am the next morning. Most of the SST climbers were back from Everest now and everyone was at the Fairfield or Aloft hotels. It appeared I was one of the few cheapskates who hiked out and most other climbers helicoptered back from basecamp. I met up with Matthew and Steven for a big Indian lunch, then Steven and Elena for a buffet dinner at the Aloft hotel. I tried to cram in as much food as possible since I’d lost a lot of weight on Everest, but it’s not possible to make up for all that in just two meals unfortunately. Made it to basecamp After dinner I quickly repacked one duffle worth of gear for Kangchenjunga. Unfortunately one of my bags of gear was still stuck at Lukla, but Steven lent me crampons, harness, and helmet just in case I couldn’t recover my gear. May 27 The next morning I left the hotel at 5am and met up with Pemba and a three-man rescue team at the airport. We would all head to Kangchenjunga together. We crammed our packs and gear into a helicopter and soon took off. The plan was to stop at Lukla, which was on the way, then change helicopters and continue. It was a scenic one-hour flight, and we soon made it to Lukla in increasing clouds. I found my duffle in a pile of bags under a tarp outside the airport, and switched out my crampons/harness/helmet from the bag for Stevens. I was soon ready to go again, but the weather had different plans. The clouds got thicker and it started raining. I hung out in the helipad terminal with a bunch of other climbers killing time. I’ve found that basically all expeditions are characterized by the “hurry up and wait” situation. That morning I had rushed to make an early morning flight, only to wait and kill time the rest of the day. Indeed, the weather never improved, and I spent the whole day milling around the terminal killing time. In basecamp By 4pm Pemba made the call that it was too late to fly out and we needed to spend the night in Lukla. We walked over to the Everest House Hotel, ate dinner, and soon went to bed. I was instructed to be back at the terminal ready to go by 5:30am the next morning. May 28 I got to the terminal a bit early at 5:15am, and was of course the only one there for the next hour. The weather was still socked in, and I suppose I could have easily slept in a lot longer. Over the next few hours some climbers trickled in, until the terminal was full by 11am. The clouds gradually started lifting and a few helicopters flew in and out. By mid afternoon the SST helicopter made it to the helipad. It had to make a few trips before it could take us last, though. It made a shuttle trip to Namche first. Then they removed all the seats to save weight and headed up to Camp 2. The rescue team looking for Szilard on Everest had made the summit but found no trace of him, unfortunately, and had descended back to Camp 2. The Khumbu Icefall had been closed by then with all ladders removed, but the team got extracted by the helicopter from Camp 2 back to Lukla. By mid afternoon it was our turn. I loaded up with Pemba and the rescue team and we finally took off. We headed due east in marginal weather, zipping above jungle and villages. We went for around an hour, starting to head up valleys to the northeast, but then the pilot suddenly descended and landed on a small helipad at Tapethoke village. The pilot had been on the radio with a pilot from an Elite Expeditions helicopter up ahead of us and the weather was too bad to make it to basecamp. The other helicopter had been stopped at Tseram, so we decided to stop there. In basecamp A few locals got out to help direct the landing, then they showed us to a small guest house. The village was pretty small and I bet they don’t see too many outsiders. There was a very rough jeep track going through, so it is accessible, barely, by road. They killed a rooster and we had chicken soup with dahl bat that night. The sherpas tried to convince me to eat sherpa style with my bare hands but I managed to find a spoon to eat with. It seems a lot cleaner to eat rice with a spoon to me. May 29 The next morning the skies were clear and we took off at 5:45am. It was a short and scenic flight up the valley to the edge of treeline at Tseram at 3700m. The helicopter couldn’t go fully loaded all the way to basecamp at 5400m so had to make shuttle runs from there. We unloaded everything, then Pemba and I got in with our gear while the rescue team waited. We helicoptered up to 5400m and landed on a small pedestal of rock sticking up from basecamp. The view from basecamp The basecamp location was amazing. It was a peninsula of rock jutting out between two glaciers and sticking up enough that it was sheltered from any avalanches from above. Even at its height there were small patches of grass growing on it. Kangchenjunga loomed above behind camp, and yellow tents were scattered all over the peninsula. It appeared only Seven Summit Treks and Elite Expeditions still had camps there. A handful of climbers were milling around, having recently successfully summitted. I got out and soon ran into Flor, whom I’d met on K2 last year. She’d summitted a few days earlier and had known Luis, the climber the rescue team would be looking for. There were a half dozen climbers all getting ready to fly out on the same helicopter. Lots of Sherpas would stay to run the camp while we were there. I was ushered into the dining tent and served a great breakfast. I stuffed as much food down as possible since I was still kind of in recovery mode from Everest. The helicopter did one more shuttle run and got the rescue team in, then shuttled a bunch of climbers out. More basecamp views The rescue team quickly packed up and started up, but it didn’t seem like Pemba was in much of a hurry. It was only 7am and there was plenty of daylight left, and the weather was perfect. My forecast from Chris was for great weather today, and sunny for the next four days, but increasing summit winds each day. It seemed to make the most sense to me to summit as soon as possible before the winds got too high. I told this to Pemba and he went and talked to the Elite Expeditions team, which had just arrived. Their plan was to take a rest day in basecamp and start up the next day. This didn’t make any sense to me. All packing could be done within an hour and we would have plenty of time to make it up to camp two or three. We had just rested the past two days with the bad weather delays. The rescue team had just started up and they were planning to make it to camp 3 that night. But since the Elite Expeditions team wasn’t going up we had to also wait. This is one reason I like going unguided, so I can make all decisions on my own. But I was basically obligated to go with everyone else. So I reluctantly unpacked my gear, found a tent, and tried to nap the rest of the day. I suppose one good thing about all these delays was that I actually got three unexpected rest days, which I probably needed anyways. And the delay in Tapethoke village gave me another night at low elevation, which probably helped with recovery. Hiking up to camp 1 The Elite Expedition Sherpas were planning to move to camp 2, then camp 4, then summit June 1. Chris’s forecast was for summit winds 25-35mph on June 1, which seemed marginal. Generally I want winds less than 20mph for summitting without O2. With O2 I’ve heard a common threshold is 30mph. Supplemental oxygen warms the body up so you can tolerate more extreme wind chills. So June 1 would be marginal while May 31 would have been acceptable in my view. But the Elite Expedition Sherpas said the route up the southwest face is generally sheltered from the winds, so you really just experience them briefly on the summit ridge. Chris confirmed the winds were indeed from the WNW and that ought to leave most of the route sheltered. The sherpas had done this mountain plenty of times so I had to trust they knew the conditions. May 30 The next morning we got ready early and by 8:30am the Elite Expedition team started up. So we started up behind them. Pemba and I split the group gear (tent, stove, fuel) and he said the rescue team had taken up a few extra oxygen cylinders. Still, my pack was around 65 pounds with the down suit, -20F sleeping bag, and tent strapped on. Nearing camp 1 I noticed the clients with Elite Expeditions didn’t seem to be quite as loaded down. They just had small day packs. It appeared there were a lot more sherpas in that team to help carry gear. There was even a professional photographer along and a few guides! I’m quite certain I paid a lot less than they did, though, and I was fine with carrying all my own gear. Despite this, Pemba and I still somehow managed to pass most of the climbers and ended up near the front of the pack. We started out hiking through a talus field, then went up a gradual snow slope and eventually hit a set of fixed lines. The slope was steep enough that you didn’t want to fall, so I was happy clipping my ascender on. It made me a little nervous that most of the sherpas tended to just clip a beaner on but not their ascender. This meant if they slipped nothing would stop them and they would run in to the climber below. In fact, I’d heard on Dhalguiri earlier this season a sherpa in this situation had slipped, crashed into the climber below, and broken his leg! Traversing to camp 2 Luckily no incidents like that happend on this trip. We made steady progress up the snow slope, which eventually got quite steep. We then made a long traverse and hit camp 1 at 6100m on a ridge. I’ve heard camp 1 is really just used on early acclimation rotations, and indeed there was no evidence left of a camp there. We stopped briefly for a snack break, then continued. From that ridge the route actually descends a bit to the glacier below and very soon reached camp 2. We dropped down the opposite side of the ridge and arm-wrap descended a gradual slope. I rappelled one short and steep dirt section down lower, then made a short and flat hike to camp 2 around 2pm. It was only about an hour between camps 1 and 2, so I can see why camp 1 soon gets skipped. Camp 2 was on a large flat section of glacier at 6200m and looked very safe from any rock or ice fall. There were already three tents set up there from Satori Expeditions and 8K, and I think Elite Expeditions had arranged for those to be left there for them. The other climbers jumped in those tents while Pemba and I set up ours. I’m glad we brough the SST tent because it weighed about the same as mine but was 50% bigger! Camp 2 We soon threw our stuff inside and Pemba started melting snow. A steep icy headwall loomed above between us and the summit and I could make out an orange tent on a bench near the top. That was camp 3, where the rescue team had made it the previous night. Higher up in the distance we could make out a snow gully leading up towards the summit, and there were a few climbers in it. That appeared to be the rescue team searching for Luis. We rested the remainder of the afternoon, and after an early dinner went to bed at sunset. May 31 The sun woke us up at 4:30am and we were soon packed up. This time we all started out in down suits and I left some extra gear to try to save weight. Pemba advised that I could just wear a base layer under the down suit and leave my jacket, snow pants, and extra layers behind. On Everest I had worn absolutely every layer and been barely warm enough, but I guess breathing supplemental oxygen would take care of keeping me warm. Climbing up to camp 3 The thought had crossed my mind to just hang the oxygen mask off my neck and not use it so I could still get a no-O2 ascent. But the more I thought about it the worse that idea seemed. We were already planning to go up in conditions that were too windy to safely go without O2 in my mind. Pemba said the group planned to start at 7:30pm that night to summit at sunrise. That gauranteed going mostly at night, when I was at most risk of getting frostbite with no O2. I would really want to start more like 1am to minimize time at night, but I had to go with the group so that was not possible. Also, I would be carrying two oxygen cylinders, which each weighed 10 lbs. It would be silly to carry 20 lbs of unneccessary and unused weight on my back if I didn’t use the O2. I couldn’t just leave the O2 and go on my own schedule because SST had told me I was required to go with O2 and sherpa. So I was basically cornered into going with the group with the O2. At least it increased chance of success, even if a bit less honorable than I had hoped. So I ditched the unneccessary gear, and since I wore my down suit my pack was considerably lighter. I kind of wanted to leave my sleeping bag too, since we only planned to rest a few hours in the daylight and not sleep at camp 4. But based on my experience on Everest pulling all-nighters at camp 4 there without a sleeping bag I figured it was wise to bring it just in case plans changed and we ended up needing to sleep at camp 4. Above camp 3 By 5:30am we rolled out of camp and started up the flat glacier. As before, Pemba and I soon found ourselves near the front of the pack. As we reached the base of the steep headwall we saw the rescue team of four sherpas coming down. They were dragging something in the snow and that didn’t look good. As they got closer I could tell it was the body of Luis wrapped up in a tarp. It had been nearly a week between his accident and them arriving due to the weather delays, so I suppose it had always been unlikely they would find him alive, unfortunately. We jugged up the steepening ice and snow slope, and it soon leveled out just below camp 3. A small ice avalanche had wiped out part of the fixed lines there, so we had to unclip briefly. Higher up I took a few ice screws from a sherpa and built some new anchors for the rope and did some re-directing to make improvements. We soon reached the small bench that is camp 3 and took a break. By this point some of the Elite Expedition clients had already started using oxygen, I think starting around 6500m. The plateau at 7100m There was a single tent there and some Elite Expedition sherpas took it down to move it to camp 4. They had really planned things out well, having tents left on the mountain for them so they didn’t have to carry as much from basecamp. The route got quite steep just above camp 3, but then did some traversing and climbing over small shoulders. Eventually Pemba, I, and Dawa were far in the lead and Pemba took over breaking trail. The rescue team had been up there that morning but the wind had drifted their tracks over. When we hit 7100m the slope leveled out to a big bench and I mistakenly thought this was camp 4. But Pemba said it was the next higher bench. We took a brief rest then continued. The route dropped down into a small valley then ascended up a steep ice slope. There were no steps kicked in and we took turns on the rope. Just around the corner from the ice slope we finally arrived at camp 4 at 7300m by 2pm. The short descent before camp 4 As before Elite Expeditions had an 8K tent already set up waiting for them. Dawa jumped inside while Pemba and I kicked out a platform and set up our tent. The slope wasn’t too steep, but it did still take a lot of effor to kick out the platform without ice axe or shovel breathing the thin air at 7300m. More Elite Expedition crew soon showed up, and everyone except me, Dawa, and Pemba was breathing supplemental oxygen. I was feeling pretty good at that elevation. I’d already spent about 48 continuous hours above 8000m without oxygen on Everest a week ago so 7300m wasn’t a problem. Dawa had been very generous to melt us some snow while we were making our tent platform, so we threw all our gear in the tent and laid down to rest. Pemba put his oxygen mask on and started breathing, but I thought I should save any oxygen for summit push emergencies. And I was breathing fine anyways. Arriving at camp 4 Pemba then gave me a lesson in how to use the system. I’d never used oxygen before so had no idea what was going on. He had brought a third regulator as backup, which comforted me. We tested that two cylinders fit in my backpack with the pressure valves visible. He showed me how to put the mask on, and said I shouldn’t wear a helmet since that made taking the mask off to eat or drink difficult. I said I didn’t care and I was definitely going to wear a helmet. There’s always risk of rockfall or icefall in the mountains. I said if I was thirsty I’d just take the helmet off then take the mask off. The regulator went in increments of 0.5L/min up to 4L/min flow rate. I’ve heard more expensive setups go up to 8L/min and lots of Everest climbers use that flow rate. But that means they need to have more cylinders brought up. Pemba said 2L/min would be a good rate and that should last 6-9 hours. We would start that immediately and that would probably get us to the summit. Then we would switch to a second bottle for the descent. I would carry both bottles, and he would carry a third as spare just in case. Then he would just use two. I think the plan was each of us would just use two but the third was a spare for either in case of emergencies. Testing out the mask I’ve had multiple friends have their regulators break on summit push on Everest. I also heard Darren had his oxygen run out before his sherpa noticed on his Everest push and he was feeling pretty crappy and starting to black out before it got switched. These stories make me nervous about relying on a mechanical system like that when unacclimated. I was comforted by several facts, though. I was already acclimated enough to summit without oxygen, so would be perfectly fine if the system didn’t work. I just might move slower and get colder. Pemba had a spare regulator that we verified worked. And, we were with a big group so among all of us there were plenty of spare components and cylinders. We took naps in the afternoon, then had an early dinner. I had a very strong appetite and had no problem finishing my two packs of Ramen noodles and quarter pound of extra sharp cheddar cheese. I don’t often have that strong an appetite above 7000m, so this tells me I was in fact very well-acclimated. By 7pm the sun set and we started getting ready, and by 7:30pm we were out of the tent and moving at the back of the big pack of 15 other climbers. Starting out just after sunset This was the first time I had breathed supplemental oxygen, and I was very curious how it would affect me. I’ve heard people say it lowers the apparent altitude by a few thousand meters, so I expected to feel like I had down at basecamp. It was still kind of hard work walking around down there with a pack so my expectations weren’t too high. Maybe it would help an extra 20%. What I actually experienced felt like an extra jolt of energy with each breath. After a few steps I’d get a little tired, then I’d suck in a breath and instantly be back up to full strength with energy ready to power forward. I kind of thought of myself like a cyclist on EPO in the Tour de France. I basically had unlimited energy, and something felt not quite right about that, like I hadn’t earned it. Hiking up with the EE team I could basically go twice the speed as I could without supplemental oxygen, and never got tired. And this was on a modest 2L/min. Could people on 8L/min on Everest be getting 4x the extra energy boost as me? I’m not sure if it scales that way, but no wonder oxygen use is common 8000m peaks. I think the only people that truely understand this advantage are the ones that have climbed 8000ers without oxygen and also tried it with oxygen. (I’d previously climbed Broad and K2 without O2 and gotten to 8500m on Everest without O2). As an added bonus, my fingers and toes never got cold. Not even a hint of being numb. If I was without O2 like on Everest I’d have to be stopping every 10 minutes to warm things up. But now I could just go continuously for hours, never needing to rest or warm up appendages. In my experience it is an order of magnitude easier to climb with supplementary oxygen than without. For better or worse, I was definitely going to make the summit this time. Looking back towards Jannu in the moonlight We generally stayed together as a big 17-person group down low, and I commend the sherpas in the front for breaking trail. Fortunately the tracks from the rescue team were still around so I don’t think it was quite as bad breaking trail. As we got higher the team started spreading out, with two EE sherpas and client in the front, then me, Pemba and Dawa all making up the lead group. Behind us the remaining climbers started slowing down more. Progress was slow and steady, and we didn’t stop for any breaks for the first five hours. That’s the power of supplemental O2 for you. By 1am we took a 5-minute break to eat some snacks, and then a few hours later we stopped again for a quick water break at the base of the rocks. Navigation can sometimes be problematic on Kangchenjunga I’ve heard, but an advantage of us coming at the end of the season was that other climbers had already figured out the route and left the fixed ropes there for us. We just had to jug up them. Sunrise on Yalung Kang June 1 The steep snow slopes got a bit tedious but then around 3am the climbing got more interesting when we hit the base of the rock band. There was a little bit of a traffic jam going up but when I got to the rocky section it just seemed like fun scrambling to me. Maybe that’s since I do a lot of mixed climbing in the winter in washington that I knew exactly how to wriggle up the features. We crested one rocky section, then started a traverse. We were then stalled a bit as the three lead climbers figured out a way up a tricky section. By then it had been 8 hours and I was worried about my oxygen canister running out at in inconvenient spot. Since we were already stopped I asked Pemba to check, and indeed it was about empty. He quicky switched the hose to the other canister and we continued up. Hiking up the final snow slope We scrambled up one final rock section then topped out on a snowy ridge just as the sun was coming up around 5am. From there it was a short snow traverse, then climbing up another short steep snow slope to the final summit pyramid. We traversed on rocks around the base of the pyramid, passing one old dead body lower on the rocks. Up until that point the wind had been mercifully light, but above us on the summit it looked like it was ripping very fast. Maybe Chris’s 25-35mph forecast was actually an underestimate! Though he did say it would be at its lowest at 6am, and it was almost that time. The group of three in front of us crested the ridge and I soon followed. Amazingly, once I poked my head up over the ridge the wind seemed to die down and was almost calm! I had feared it would be a knife-edge rock ridge but, while my side was all rock, the other side was a gentle snow slope. The final rocky bit before the summit I easily marched up the snow slope and reached the summit at 5:30am, ten hours after starting. I was the second one up there. The photographer for Elite Expeditions had gotten their first and was waiting to take pictures of the clients. Conditions were perfect. Only partly cloudy with great views around, almost no wind, and not even too cold (probably because I was breathing the oxygen). I got a few pictures and a brief video, then Anna Gutu from EE made it up and I took some pictures of her. She returned the favor for me, but then my camera froze and wouldn’t turn on! I thought keeping it warm in my inner pocket would help, but I guess it was actually kind of cold up there (forecast -15F) and it had gotten too cold. The only way to salvage it in this situation I’ve found is to plug it in to an external battery. But I didn’t want to fool around with that on the summit so I called that good enough for pictures. I yielded the top to the other climbers coming up and stood off to the side admiring the view. But I soon started getting a little nervous. More and more climbers were trickling up and it seemed risky somebody would knock another person over the edge with all the jostling for pictures. So I told Pemba I was good and we should head back down. On the summit Ten minutes had been plenty up there to admire the view, plus if we were the first ones down we could rappel all the steep lines and not have to wait in a queue. This would be especially important if the weather turned sour, and it was indeed supposed to get windier over the day. We made fast progress down, and took turns rappelling the steep lines and arm wrap descending the others. Pemba was much faster so he went first, and we soon spread out enough that I didn’t have to wait at all to rappel. At the base of the rocky section I noticed a pack sitting by itself in the snow with a set of skis sticking up next to it. This must have been from the climber Luis that the rescue team found. Way lower on the slope I had seen a few stuff sacks earlier, also likely from him. I arm wrapped down the snow slope, though managed to rappel a few of the steeper sections. By 8:30am, three hours after summitting, we both staggered back into camp 4. It felt good to pull off the oxygen mask and finally be breathing normally. It turned out we had a lot of extra oxygen. I had only used a little over one canister and Pemba the same. So we had a few extra canisters. There was no need for any oxygen going down, and empty canisters are much lighter, so we opened the valves and released the extra gas. It felt kind of wasteful, but didn’t make sense carrying so much extra weight down. Back at camp 4 Pemba proposed a two-hour break, then we would descend back to basecamp. So I repacked everything, then laid down for a brief nap. We had just pulled an all-nighter so both appreciated the rest. By 10:30am we got out of the tent and started taking it down. There had been a suggestion that we just leave the tent there, but there were no other teams coming up that season that could use it, and it would just become trash. I volunteered to take it down since I’d carried it up. By 11am we were all packed up and heading down. My pack was now monstrous again since it was too hot to wear the down suit and I had to put it in the pack. By then some of the EE team had made it back, but most were still working their way down from the summit. I think our time of 3 hours down was kind of fast. Descending back down We made good time down from camp 4, again enjoying the benefits of being first since there were no queues to wait in and we could rap down any line we wanted. (For reference, two people can climb up a rope at the same time but two cannot rappel down a rope at the same time – they must take turns, which can slow things down descending). We passed through camp 3, then took an extended break at camp 2. It was getting hot and I was out of water by then. The rescue team had been in camp 2 the previous day and was hoping for a helicopter extraction, but for some reason conditions weren’t good and the helicopter couldn’t land. So they had moved everything to camp 1 and would get extracted from there. Meanwhile, they had generously melted a pot of water and left it for us, and left a bag of coke bottles for us! Last look at the upper slopes I chugged the water and Pemba cracked open some cokes. I don’t really like carbonated beverages, but I was low on energy and liquid and figured the sugary beverage might help. Pemba passed out more cokes to EE sherpas coming down and everyone was in good spirits. Some clients came down and took naps in the three tents remaining there, and Pemba and I soon packed up and headed out. I really was not looking forward to the uphill to reach Camp 1 after already putting in a big day. I think the coke didn’t agree with my stomach since I don’t usually drink carbonated bevereages. At any rate I was not feeling 100% approaching that hill, and it took me twice as long as it should have to make it up. Descending below camp 1 I eventually made it and caught up to Pemba resting at Camp 1. From there it was easy arm wrap descending down. A few sections of the route had been hit by small loose wet avalanches, likey earlier that day. It was indeed kind of hot there in early June. But by the time we got there evening clouds had built and the slopes were stable. We dropped back down and eventually staggered in to basecamp around 530pm for a 22 hour day. We had an excellent chicken and spaghetti dinner, and I even got to take a warm bucket shower before bed. June 2 Back to basecamp for dinner An Elite Expedition helicopter arrived at 6am and immediately started shuttling climbers out. That would be the only helicopter and it had to service everyone. I quickly packed up and took my turn to shuttle down to Tseram. There we all waited for a few hours drinking tea at the local teahouse. When all the climbers and sherpas were out the helicopter then started shuttling us all to the Taplejung air strip. This was the closest village with a paved road to basecamp. I had been told the whole SST crew would get flown to Kathmandu that morning. This was important since I had purchased a flight out of Kathmandu for that evening. I had purchased it just before heading in to Kangchenjunga, and thought building in four buffer days would be enough. But with the weather delays and the delay in starting out of basecamp it had eaten into my buffer time. The flight could still work, but then Pemba told me we would not in fact be going to Kathmandu that day. The one helicopter would take the elite expedition clients back, but the sherpas and I would be taking a 10-hour jeep ride to the nearest major airport at Bhadrapur and taking a scheduled fixed wing flight to kathmandu the next day. Flying out That was a little frustrating, but I guess it was my fault for not building in enough buffer days. I called up the airlines and it turned out the flight cancellation fee was almost exactly the price of the flight. So I basically lost $1000 by that mistake. However, I decided I’d rather stick it to the airline and just not show up instead of cancelling. That way they couldn’t resell the ticket to make more money. I lost an extra $30 or so but it felt worth it to me. I figured I basically gained $1000 by hiking out of Everest basecamp instead of flying out, so maybe now I was even. That afternoon Pemba and I hopped in a jeep with the rescue team and we started the long, windy drive out. We crossed mountain passes and dropped way down to cross river valleys. Basically the whole way was blind turns on the side of cliffs down in the jungle. Eventually we reached Suryodaya eight hours later and stopped there for the night. June 3 The next morning we drove two more hours to Bhadrapur, then got on the 9:30am flight to Kathmandu. In Kathmandu I took a taxi to the Fairfield Hotel, and Thanes brought over my bag that SST had gotten from Lukla. I had enough spare time to meet a friend Sandro for dinner, then made my 2am flight back out for Seattle. Gear Notes: Standard 8000m gear Approach Notes: Helicopter to basecamp3 points

-

I have climbed Ice cliff and stuart col. west ridge a few years ago in prime condition in middle april. I went in yesterday for a C2C and summited Colchuck to get a eye on things. Dragon tail has triple Col coming in the ice step is just starting to form, I would attempt it in the next few weeks. As far as Stuart goes, the end of april would probably be better. As of now the ice cliff and Stuart Glacier faces are loaded and probably full of loose dry sluff with a crappy crust. The summit block and ridge lines are in there winter state also. Gerber sink is not in a condition for screws. Hopefully this weather system keeps up and forms some better route conditions. Be prepared for the spring time afternoon high winds and crappy fronts that roll in this time of year. The gate at 8mile campground is still closed and will be for some time, I hit snow at about 1.5 mi in. It was about 1ft deep and consistent at the 2 mile mark. The trail is packed to the Colchuck intersection and easy travel in the cooler hrs. If you need a second reach out and I might be able to make it work, best of luck. will load pictures soon.3 points

-

Trip: Argonaut Peak - East Ridge/NE Couloir Trip Date: 03/09/2024 Trip Report: Argonaut Peak (8,455 ft) March 9, 2024 East Ridge/NE Couloir 18 miles skiing/climbing, 10 miles snowmobiling, 8300ft gain 73/100 Winter Bulgers Eric and Nick On the summit The weekend looked to be stormy but the Enchantments zone seemed to be getting hit the latest. I’d previously bagged all the Bulgers peaks in the Enchantments in winter except Argonaut, so we decided to go for it. The route I’ve previously climbed Argonaut twice via the south face route (May, August), which ascends a steep gully to the summit ridge followed by a class 3/4 scramble to the summit. This is not necessarily the best winter route, though. In February 2022 Nick and I had been camped near the base after climbing Sherpa and planned to climb the south face route, but my updated NWAC forecast on my inreach made us too nervous about snow stability. So we bailed that time. Our East Ridge/NE Couloir route (drawn on picture taken by John Scurlock from the north) This weekend the snow stability conditions didn’t look great for that route either. But Argonaut has many different route options, generally all technical. I noticed we could ascend gentle slopes up the Porcupine Creek drainage on the south side to gain the Argonaut-Colchuck col at 7700ft keeping the slope angle low. From there we could climb one of the technical routes up to the summit. The routes might require crossing short snow slopes, but we would be roped up clipped in to gear in the rock so would be protected. We would bring a 60m half rope, hexes, nuts, cams, and technical tools. I would bring one technical tool with a hammer (for the hexes) and one ultra-light corsa straight shafted axe with a custom 3D-printed adjustable pinky rest Nick had just printed. This would allow me to plunge in snow and save some weight. We’d also each bring our custom carbon fiber ascent plates Nick had CNC milled. Unloading the sled The main route options from that col appeared to be the East Gully, the East Ridge, and the NE Couloir. Neither of us had done any of these routes but we figured we could see what looked the most reasonable based on conditions and climb that. The first record I could find of a winter ascent of Argonaut was via the NE Couloir (Lurie, Feb 2006, NWMJ). But climbing the full couloir seemed too risky with the snow conditions since it’s a ~3,000ft long snow gully and I wouldn’t want to be in the bottom if it slid. Worst case we would just cross the top of it, roped up, which would be much safer. At the Beverly Creek trailhead The shortest approach would be from the Beverly Creek trailhead, which is accesible by snowmobile. In order to beat the incoming storm we wanted to summit by noon, so that meant leaving very early. We decided to do a car-to-car push to avoid carrying overnight gear over the fourth creek pass. Friday evening we got to the Twentynine Pines staging area on Teanaway River road, unloaded the sled, and went to bed. Saturday we were up and moving by 12:30am. The road had just been groomed and we made excellent time, hitting 40mph in places. The Beverly Creek turnoff was a bit rougher, but we reached the trailhead 20 minutes after leaving the truck. Interestingly, there was a nice skin track already going up from the trailhead. This is very unusual for winter Bulgers trips. Crossing Bean Creek We followed the tracks across Bean Creek, but then they diverged west after a few miles. It looked like they might have been heading for Iron Peak. We then broke trail up to the Fourth Creek saddle, and transitioned to ski mode. We had fun turns going down fourth creek, then transitioned to skins as it flattened out. We skinned down to Ingalls Creek, trying to set a good track for our return trip. Ingalls Creek The creek was too high to rock hop across, but we found a nice fallen log across near the trail crossing. It was 8″ wide with a foot of snow on top and lots of branches sticking out. I strapped my skis on my back and started over au chaval. I karate chopped the icy snow off the top, then used an ice tool to bang off the branches. Progress was slow but this worked and made for a nice smooth crossing on the return journey. On the other side we skinned up to the Ingalls Creek trail, followed it east for a half mile, then left the trail heading up the Porcupine Creek drainage. The slopes were nice and mellow angle and the forest was mostly open for easy travel. As we got higher to more open areas the snow had a firm sun crust. We started on the west side, then crossed over to the east side and ascended into the large bowl flanked by Argonaut, Colchuck, and Dragontail. Conditions were pleasant with no wind and great views of the summits. We knew that would change by afternoon, though. Approaching Argonaut in the upper Porcupine Creek drainage We noticed the East Gully route looked like it might go, though was kind of steep. We decided to head to the Argonaut-Colchuck col to scope out the East Ridge and NE Couloir to see which one we preferreed. As we crested the ridge the wind picked up from the south, and we noticed the north side would be much more sheltered. It looked doable to ascend the East Ridge then cross over the top of the NE Couloir to gain the upper north face of Argonaut. That sounded appealing given the wind direction, so we went for that route. At the col We ditched skis at the col, then roped up. Nick started first and we shortened the rope to 30m and simul climbed. The East Ridge started getting steep soon so we dropped onto a snow ramp which we traversed across to enter the NE Couloir. We got good gear in the rock to protect a fall in case the snow slid. On the opposite side of the Couloir Nick built an anchor and we swapped leads. I kicked steps up the right side of the couloir for 30m then when the couloir dead ended at a rock face I exited up and right. Crossing into the NE Couloir This section was the crux of the route. The snow got thin and steep on a rock slab except for a thick wind deposit about 3ft deep. I had to tunnel through it Cerro-Torre-style, digging down to the thin icy layer on top of the slab to get good purchase with my front points. I kind of wished I had the custom wings on my ice tools. Eventually I excavated out an old rap anchor, clipped it, and tunneled the last bit up to the low-angle north face snowfield. In the upper NE Couloir I belayed Nick up there with a solid hex anchor and we swapped again. Nick led up the left side of the snowfield, getting a few gear placements in the rocks on the side. We eventually simul climbed up to the summit ridge, and swapped leads again. I traversed the ridge, weaving the rope around horns and getting a few intermediate pieces in. I had to make a few mixed climbing moves getting over one rock step. At last, I saw the famous tunnel under the summit boulder, and luckily it had a big enough gap to squeeze through. Nick on the summit By 1pm I made the final short mixed scramble to the summit. I belayed Nick up off the summit horn, and we were soon both on the summit. It was windy, but luckily not snowing yet. It appeared the storm was coming in a bit later than forecast, which was great news. There was no view in the whiteout, so we soon regrouped and headed down. I led the way back as we simul downclimbed the ridge and retraced our exact track back down the snowfield. We regrouped above the crux, and we decided to simul downclimb that as well. Now that the snow was excavated and good steps were kicked it wouldn’t be too hard. I put the exact same gear placements in as on the way up, and we simuled back down to our previous anchor point. There Nick took over and led back across the ramp to the Argonaut-Colchuck col by 2:30pm. Descending the summit ridge Now the storm had hit with full force, and it was extremely windy and snowy. I was jostled off balance a few times. Back at the skis we put goggles on, and decided to crampon down in the whiteout until it got more sheltered. I followed the track on my watch since our up tracks were drifted over. After 10 minutes we got back into intermittent trees and the wind died down. Unexpectedly, it then cleared out and was partly sunny! It appeared to be a brief break in the storm, and came at the perfect time. We switched to skis and had fun turns down the big open slope. Though, lower down we hit sun crust which made skiing challenging. Hiking down in the storm We switched back to crampons and descended down into denser trees. Back in the trees the sun crust disappeared and we again skied back down. The icy lower sections had changed to a small layer or corn and made for excellent skiing. We eventually reached the Ingalls Creek trail as the sun gave way to heavy graupel and snow. There we skinned back to Ingalls Creek and scooted back across the log. Last view of the south face of Argonaut We then followed our tracks back up fourth creek as darkness set in. At the pass we switched back to ski mode and made a high traverse back down the Beverly Creek drainage. Interestingly, we encountered a set of snowshoe tracks that had followed our tracks up to 5000ft. This appears to be a relatively popular area in winter! I guess the road approach is only five miles, so a snowmobile isn’t really necessary. Though I certainly appreciated being able to sled in and out instead of walk. Sledding out It was fun cruising down the drainage, and we made it back to the sled by 8:45pm. We then strapped our gear on and got back to the truck around 9:15pm for a 21-hour push. Gear Notes: Snowmobile, 60m rope, skis, technical tools, hexes, nuts, cams, ascent plates (unused but we probably should have used them) Approach Notes: Sled to Beverly Creek TH, ski to Argonaut-Colchuck col3 points

-

2 points

-